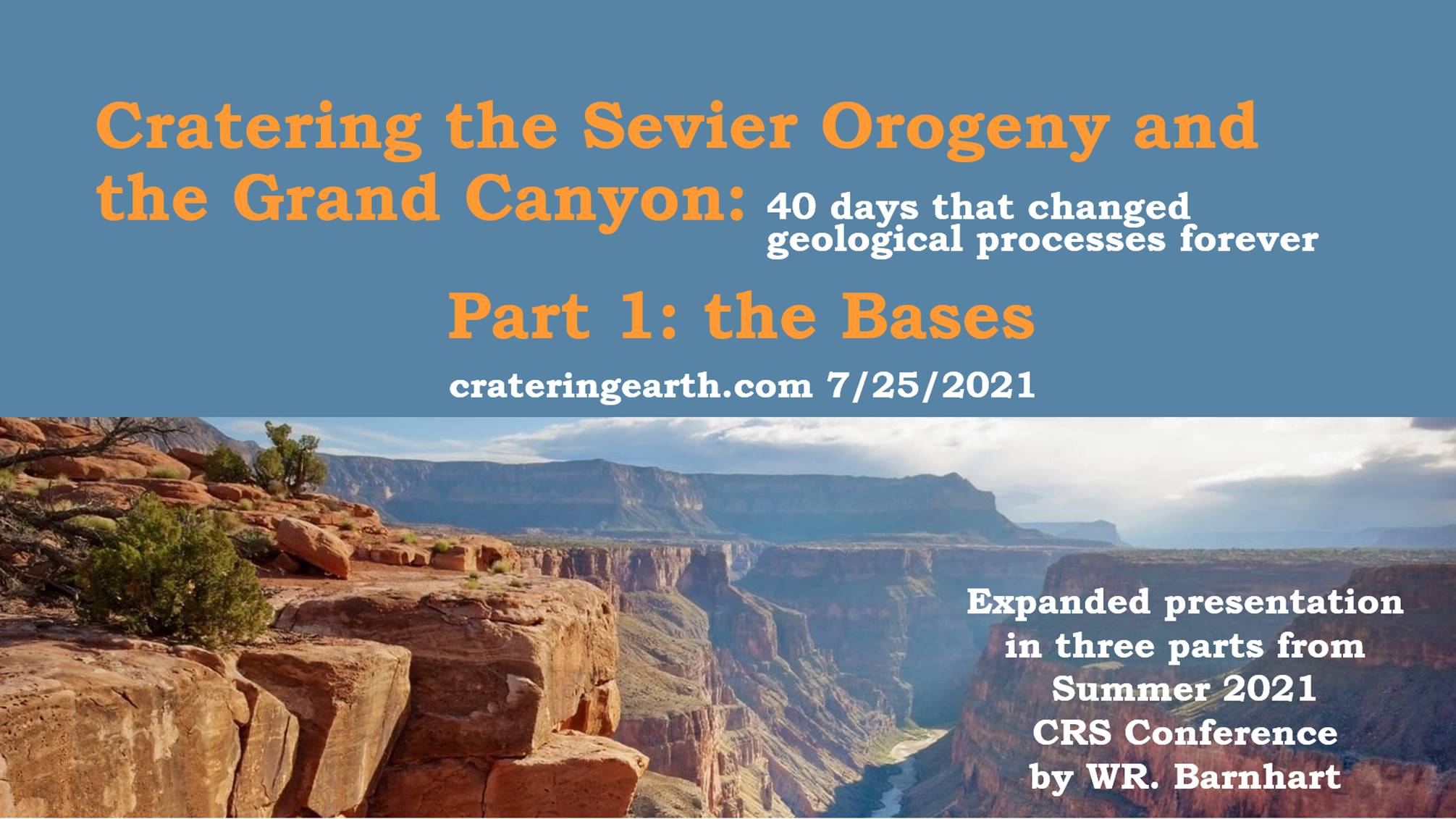

There may be no other plot of ground so often used to illustrate many of the geologic processes espoused in textbooks than the Grand Canyon. Geologist talk about it like they have the processes all figured out. Is it just possible that they have gotten it all wrong? This presentation is going to suggest unimaginable cratering was responsible for everything we see there, from the rocks, the sequence, the faults, and the actual canyon. None of it got there by geological processes we can see happening around us today. We will question if some of the processes even work the way everyone has assumed they worked. Gentle reader, do not be afraid to questions the rocks, the processes, even my model, but above all, question the assumptions both you and I have made. Our God is a God of mystery, but He is also a God of Knowing. And in knowing, He is worthy of our praise.

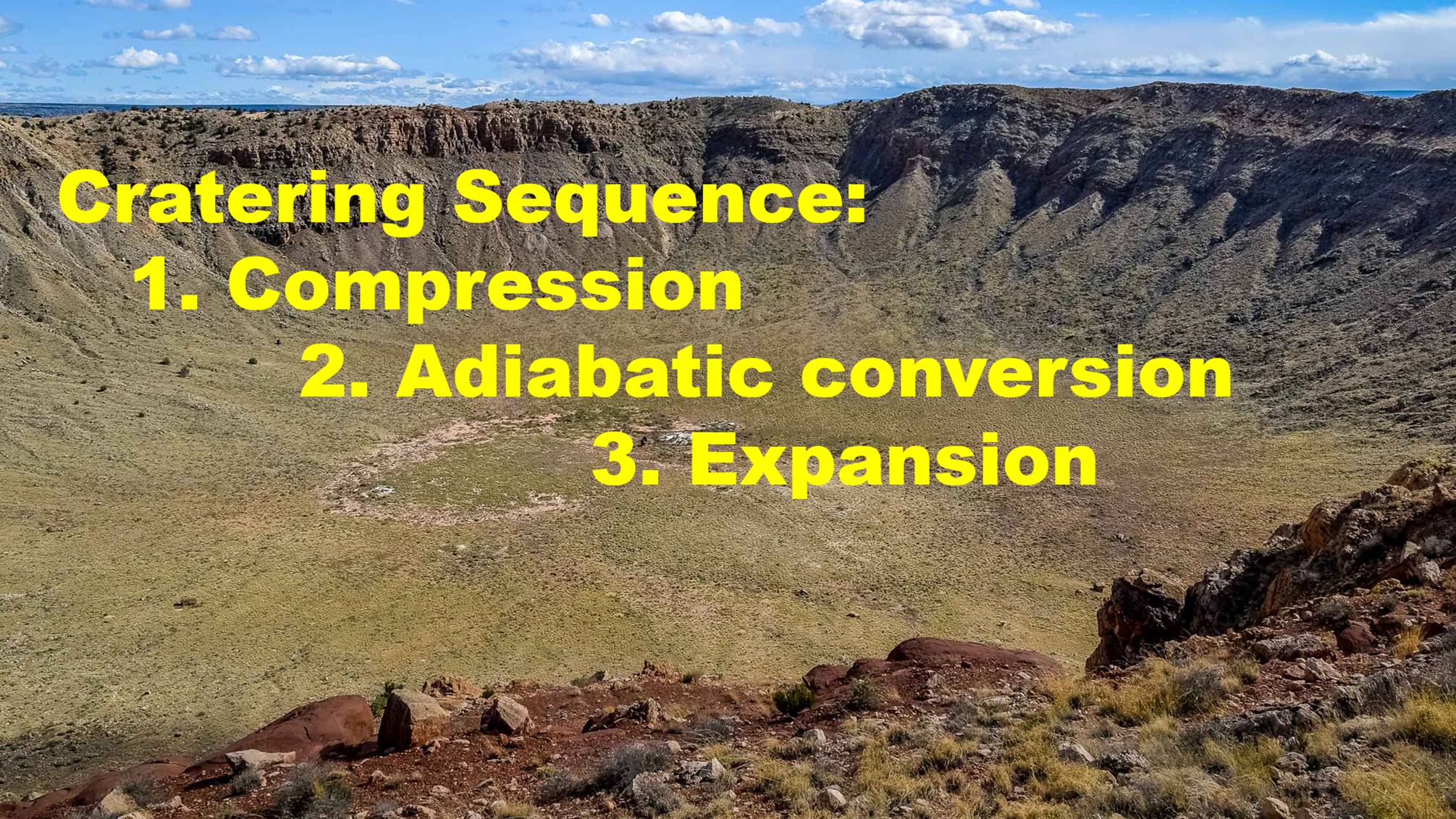

There may be no other plot of ground so often used to illustrate many of the geologic processes espoused in textbooks than the Grand Canyon. Geologist talk about it like they have the processes all figured out. Is it just possible that they have gotten it all wrong? This presentation is going to suggest unimaginable cratering was responsible for everything we see there, from the rocks, the sequence, the faults, and the actual canyon. None of it got there by geological processes we can see happening around us today. We will question if some of the processes even work the way everyone has assumed they worked. Gentle reader, do not be afraid to questions the rocks, the processes, even my model, but above all, question the assumptions both you and I have made. Our God is a God of mystery, but He is also a God of Knowing. And in knowing, He is worthy of our praise. In the previous two parts I have covered a little of how I arrived at my model of crater formation, and the cratering events that shaped some of the strata exposed in the canyon. Now we want to understand the cratering events that led to the formation of the canyon.

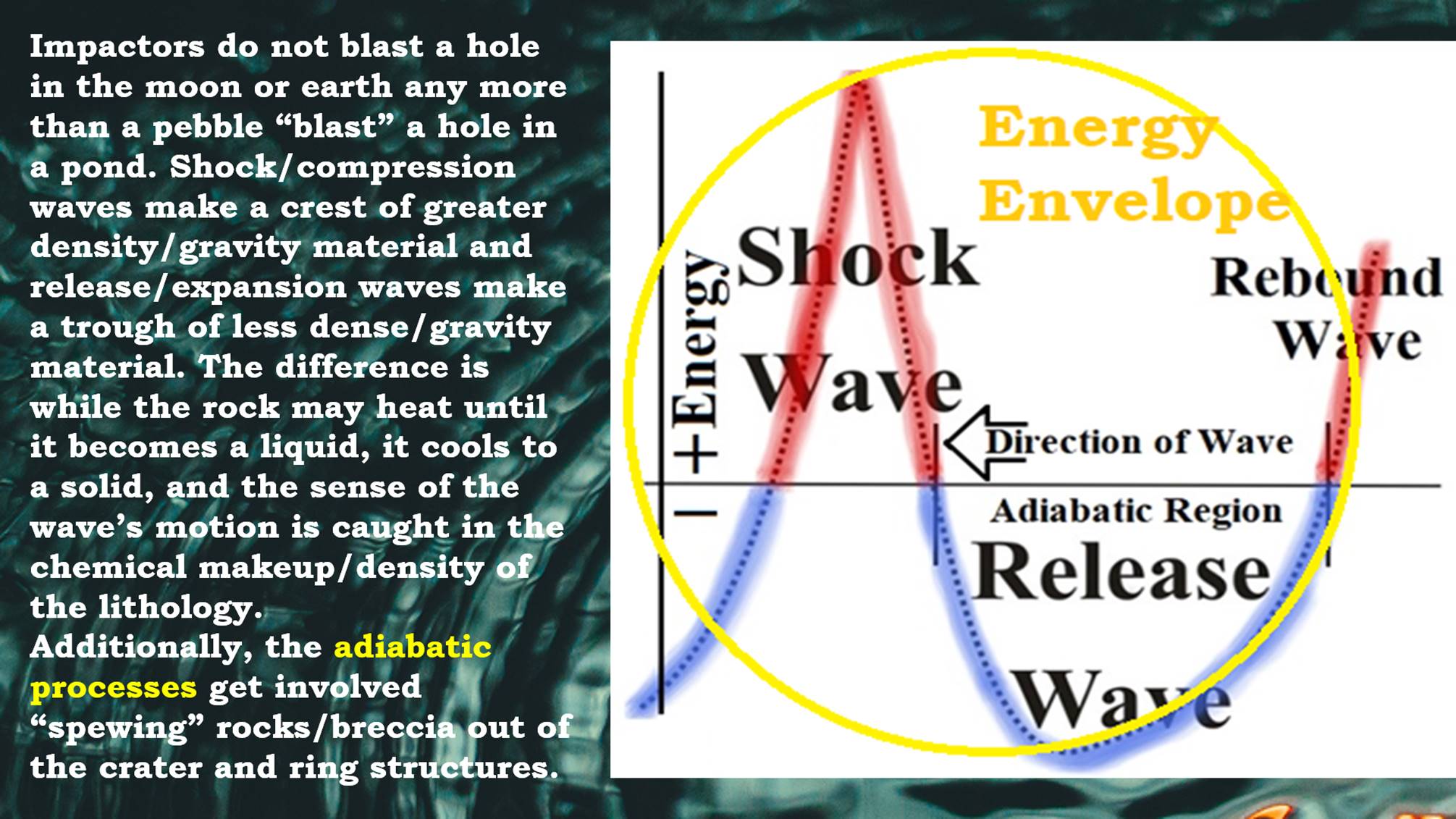

In the previous two parts I have covered a little of how I arrived at my model of crater formation, and the cratering events that shaped some of the strata exposed in the canyon. Now we want to understand the cratering events that led to the formation of the canyon. Figure 60: Redwall Cavern, a prominent landmark on the river trips is a great place to deal with the ubiquitous red color that coats much of the inner gorge. Many just say that it is Iron Oxide, but do not specify the type. Iron (Fe) has three oxidations states and forms three oxides: rust that requires water in its molecule, magnetite that is black, and hematite that is red. To form hematite requires removing three electrons from the Fe ion, which requires almost twice the energy of removing only 2 electrons (Chapter 12.). If it were rust it would keep forming and flaking off, like rust does on a piece of iron. It did not come from the Supai above that washed down as the rangers try to tell you, because it covered the ceiling of Redwall Cavern, and it could not have washed onto the ceiling all the way to the back of the cavern. Also, the hematite in the Supai Sandstone is trapped as crystals between the grains of silica sand. The black you can see on some of the far wall is not “dirt,” but chemist have identified it as oxides of magnesium, and tungsten, and it requires high temperatures to form also. All of these oxides require very high temperatures, ~1,000 degrees C (1,832 degrees F), to form. Note, the Cavern formed at the same time as the rest of the canyon and all of the other alcoves into the Redwall, which are also covered with hematite.

Figure 60: Redwall Cavern, a prominent landmark on the river trips is a great place to deal with the ubiquitous red color that coats much of the inner gorge. Many just say that it is Iron Oxide, but do not specify the type. Iron (Fe) has three oxidations states and forms three oxides: rust that requires water in its molecule, magnetite that is black, and hematite that is red. To form hematite requires removing three electrons from the Fe ion, which requires almost twice the energy of removing only 2 electrons (Chapter 12.). If it were rust it would keep forming and flaking off, like rust does on a piece of iron. It did not come from the Supai above that washed down as the rangers try to tell you, because it covered the ceiling of Redwall Cavern, and it could not have washed onto the ceiling all the way to the back of the cavern. Also, the hematite in the Supai Sandstone is trapped as crystals between the grains of silica sand. The black you can see on some of the far wall is not “dirt,” but chemist have identified it as oxides of magnesium, and tungsten, and it requires high temperatures to form also. All of these oxides require very high temperatures, ~1,000 degrees C (1,832 degrees F), to form. Note, the Cavern formed at the same time as the rest of the canyon and all of the other alcoves into the Redwall, which are also covered with hematite. Figure 61: It was Aristotle who recognized that streams move material, and Seneca recognized the power of streams to wear away valleys. Leonardo da Vinci believed that valleys were a result of their streams, but Unaweep and Grand Valleys of Colorado and the Grand Canyon are extreme examples of under-fit streams. The water flowing through them could never start to produce the vast amount of erosion that has taken place there. In the Grand Canyon it is made even worse. It is not one channel, but, a maze of side channels covering about 2,000 sq. miles (5,200 sq. km.). I have classified the Unaweep and Grand Valleys as Release Valleys (Chapter 1) from the Unaweep crater. Could the Grand Canyon have the same origin??

Figure 61: It was Aristotle who recognized that streams move material, and Seneca recognized the power of streams to wear away valleys. Leonardo da Vinci believed that valleys were a result of their streams, but Unaweep and Grand Valleys of Colorado and the Grand Canyon are extreme examples of under-fit streams. The water flowing through them could never start to produce the vast amount of erosion that has taken place there. In the Grand Canyon it is made even worse. It is not one channel, but, a maze of side channels covering about 2,000 sq. miles (5,200 sq. km.). I have classified the Unaweep and Grand Valleys as Release Valleys (Chapter 1) from the Unaweep crater. Could the Grand Canyon have the same origin?? Figure 62: Let’s start with one small but pronounced feature of the erosion, the Butte Fault. It is up to the east, telling us the shear center is to the west. The west side it thrusting up-and-over the east side. Comparing this in a diagram of the expected cratering faults, the only expected movement of earth in a cratering event would be thrust movement, reverse faults, outwards in all directions as a result of shock compression at the impact site. The formation of Normal Compensation faults would be expected as the compression drops down into the Release Valley at the adiabatic conversion site on the inside of the compression wave. Faults are not a matter of plate growth/extension or contraction/foreshortening. Horst and Graben systems and Transverse Faults do not exist (Chapter 19A). There are several things in geology that will have to be relearned, and faults are one of them.

Figure 62: Let’s start with one small but pronounced feature of the erosion, the Butte Fault. It is up to the east, telling us the shear center is to the west. The west side it thrusting up-and-over the east side. Comparing this in a diagram of the expected cratering faults, the only expected movement of earth in a cratering event would be thrust movement, reverse faults, outwards in all directions as a result of shock compression at the impact site. The formation of Normal Compensation faults would be expected as the compression drops down into the Release Valley at the adiabatic conversion site on the inside of the compression wave. Faults are not a matter of plate growth/extension or contraction/foreshortening. Horst and Graben systems and Transverse Faults do not exist (Chapter 19A). There are several things in geology that will have to be relearned, and faults are one of them. Figure 63: The Bright Angel-Phantom Creek-Eminence Break Fault is a second continuous linear that Huntoon and Sears first recognized in 1975. It is first seen at the Bright Angel trailhead, and forms the canyon to the river. From there the linear continues following the Phantom Creek canyon out over the North Rim where it corresponds with the Eminence Break on the north eastern edge of the rim. Do linears appear at random (Chapters 3-7)? Or, can their source of shear be traced back to the supposed direction of plate convergence?? Over vast reaches of the Pacific Northwest multiple authors have traced the Euler Pole for several sets of faults. They assume the Euler Pole is a pole of plate rotation, but I find their location of the pole corresponds with my location of cratering centers (Chapter 19). We are finding the same thing, and identifying it according to our different models.

Figure 63: The Bright Angel-Phantom Creek-Eminence Break Fault is a second continuous linear that Huntoon and Sears first recognized in 1975. It is first seen at the Bright Angel trailhead, and forms the canyon to the river. From there the linear continues following the Phantom Creek canyon out over the North Rim where it corresponds with the Eminence Break on the north eastern edge of the rim. Do linears appear at random (Chapters 3-7)? Or, can their source of shear be traced back to the supposed direction of plate convergence?? Over vast reaches of the Pacific Northwest multiple authors have traced the Euler Pole for several sets of faults. They assume the Euler Pole is a pole of plate rotation, but I find their location of the pole corresponds with my location of cratering centers (Chapter 19). We are finding the same thing, and identifying it according to our different models. Figure 64: (A) One map of Butte Fault that may have been taken from an old map or estimated from the terrane. I highlighted their designation of Butte Fault as two linears using corresponding labels to Figure 66. (B) Linears I located in the area using topographic clues, CGRS in white and short concentric linears shown in red. Labels as in Figure 65.

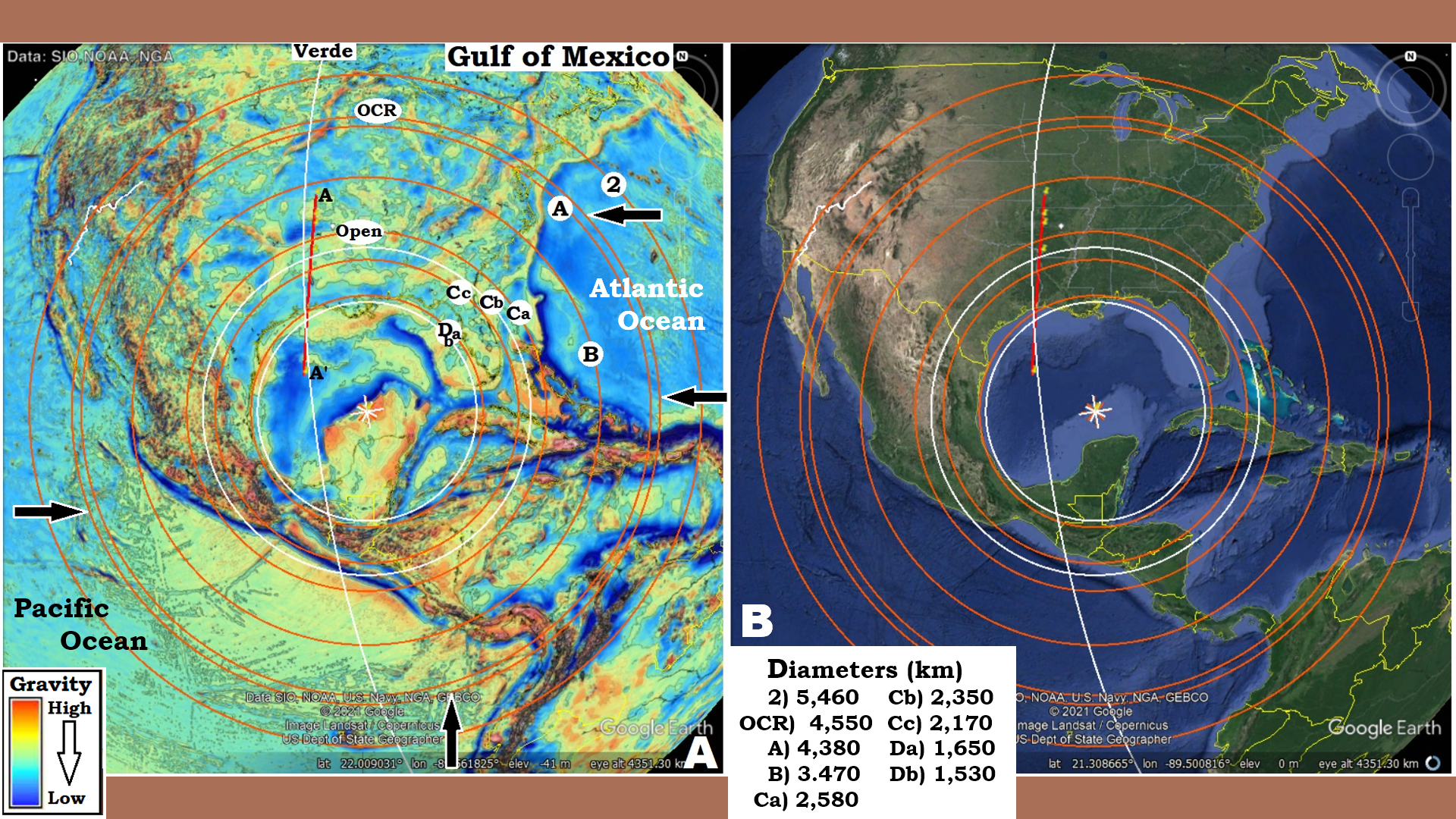

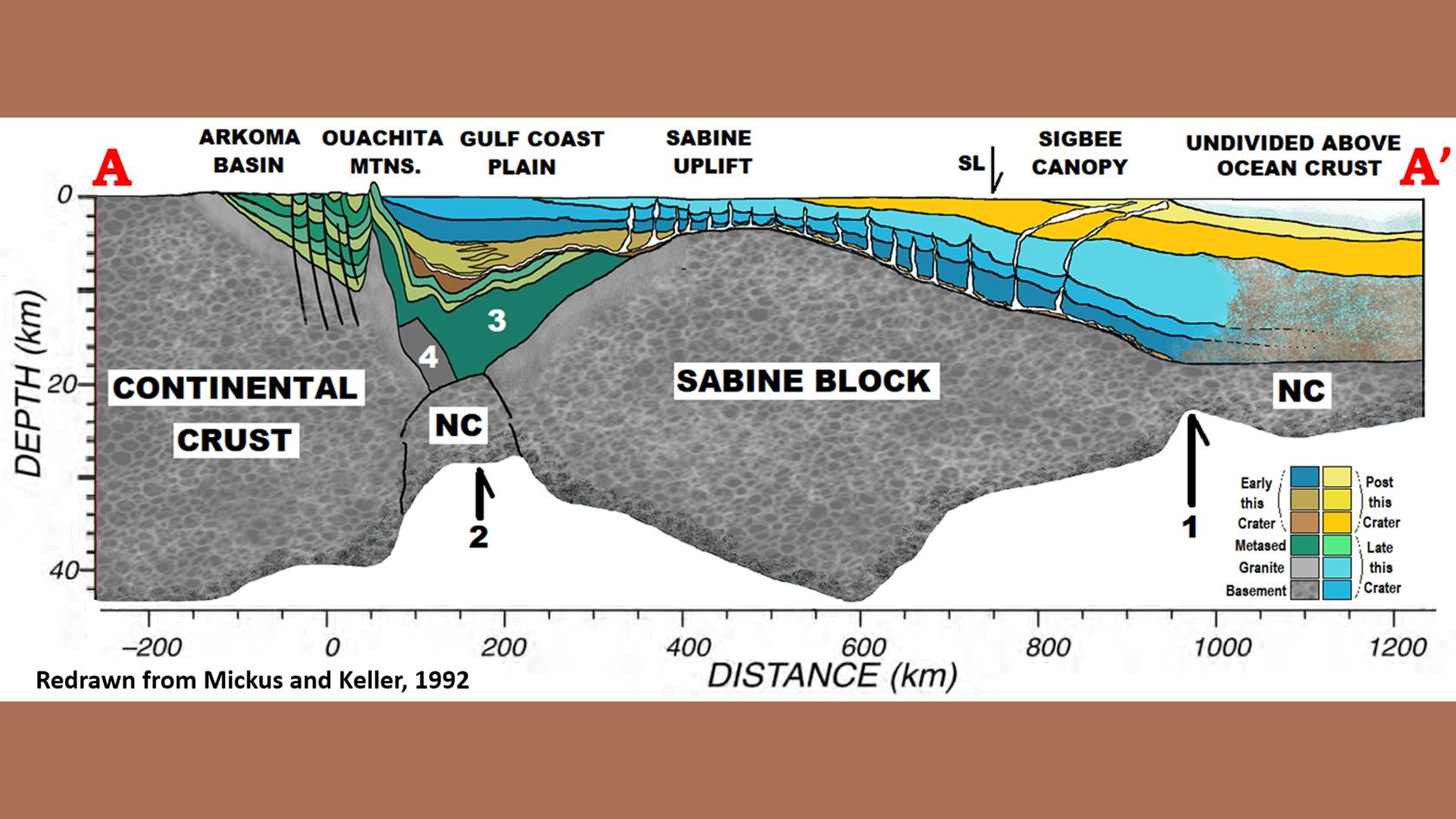

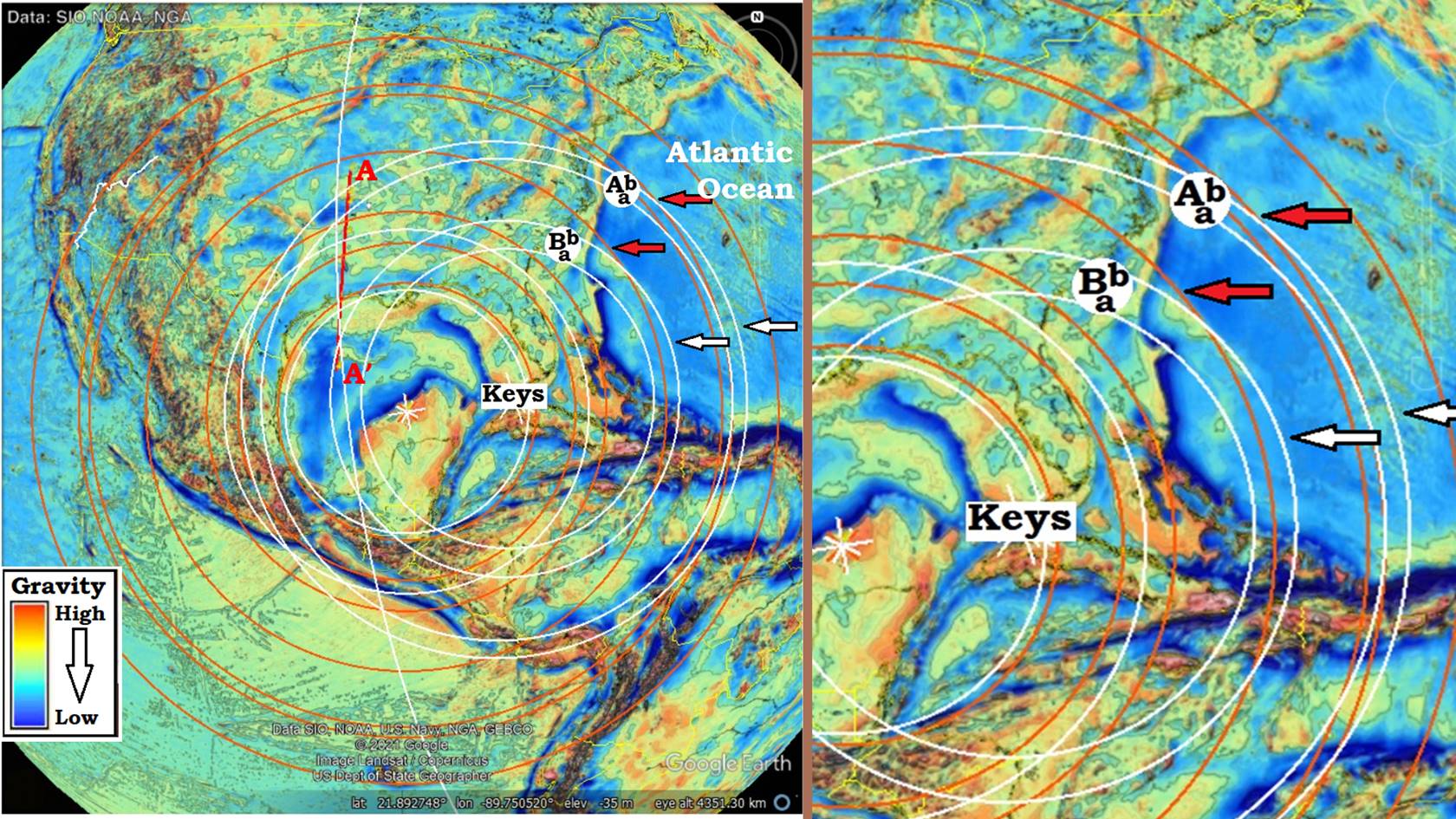

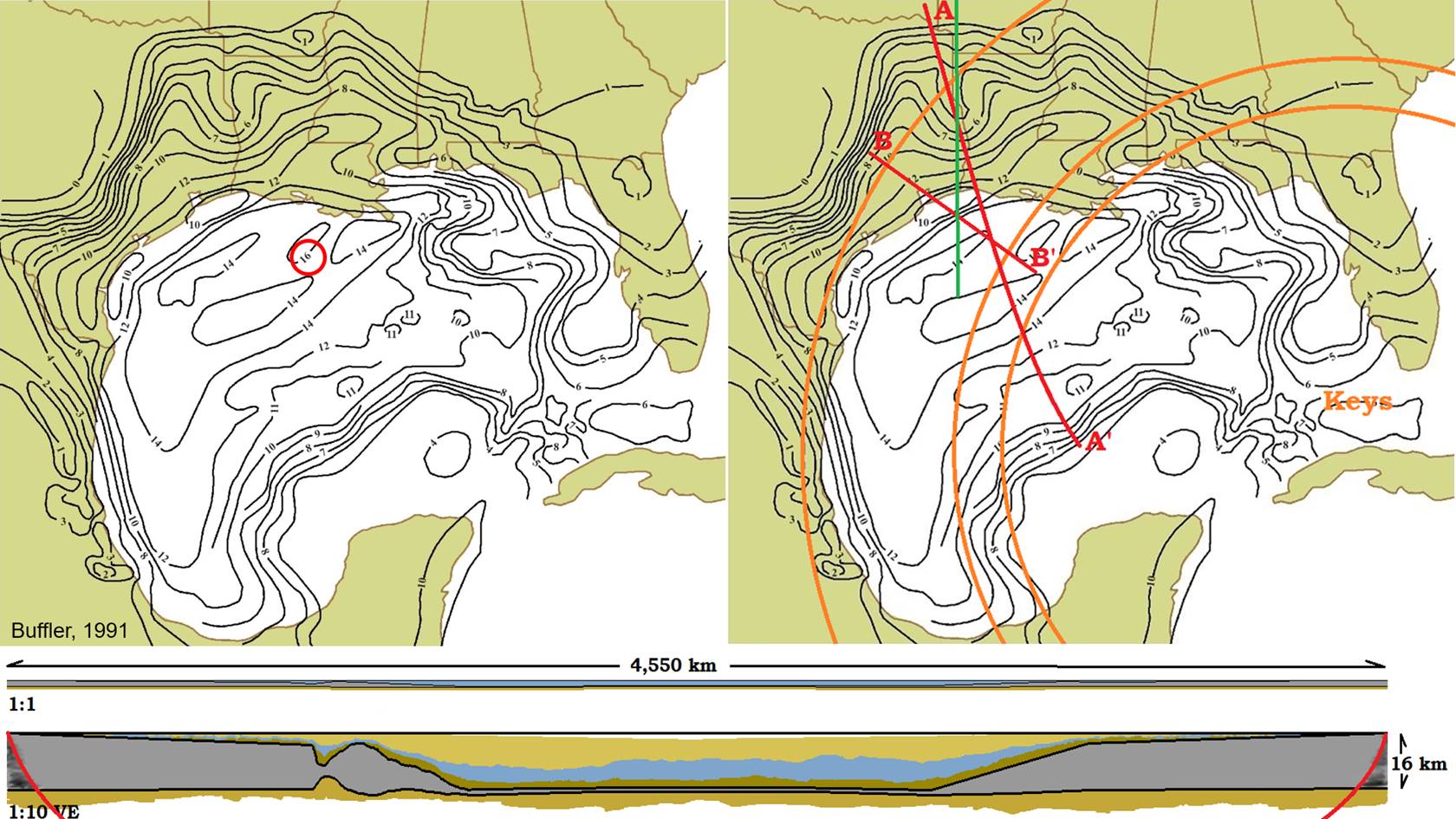

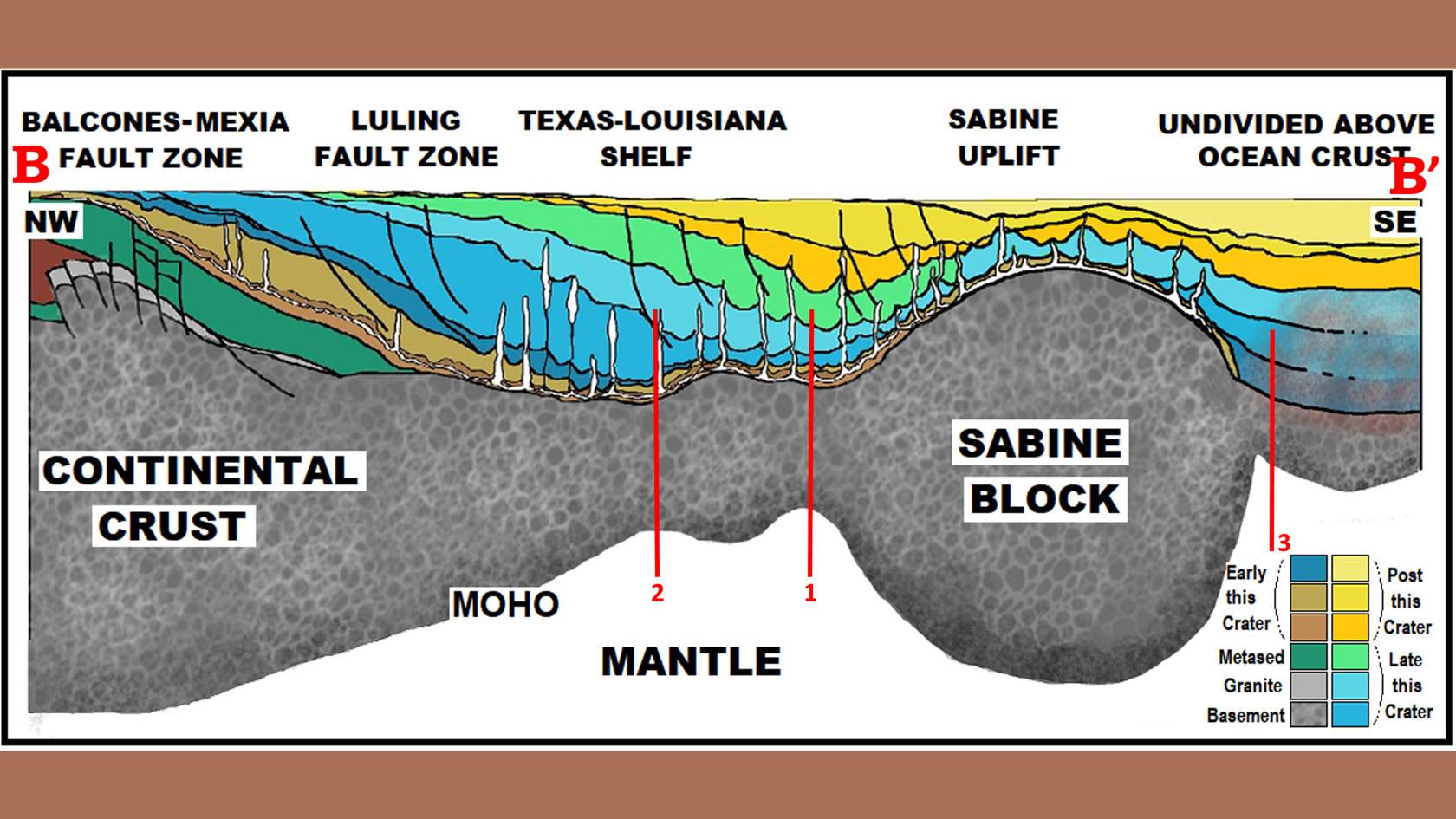

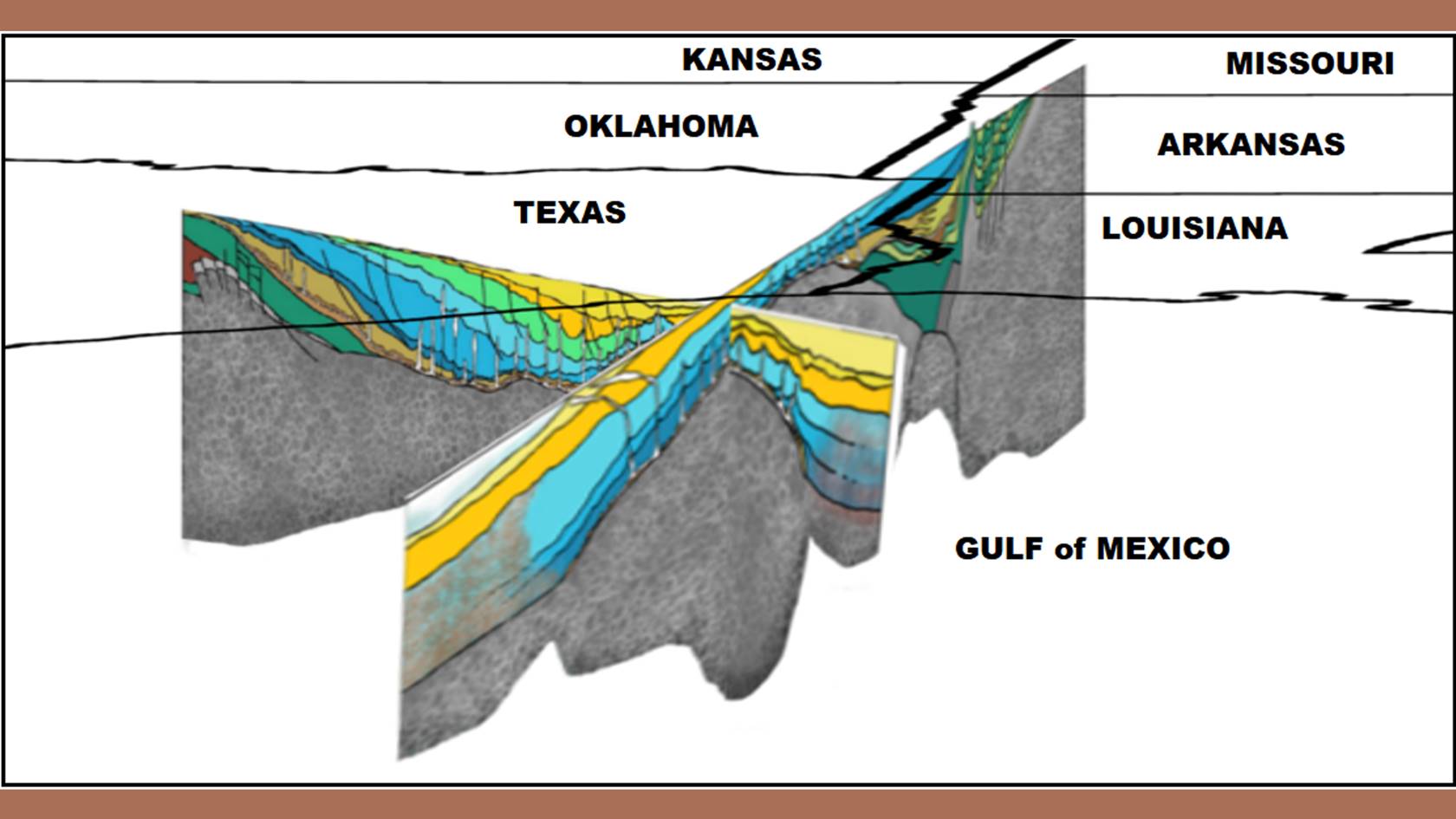

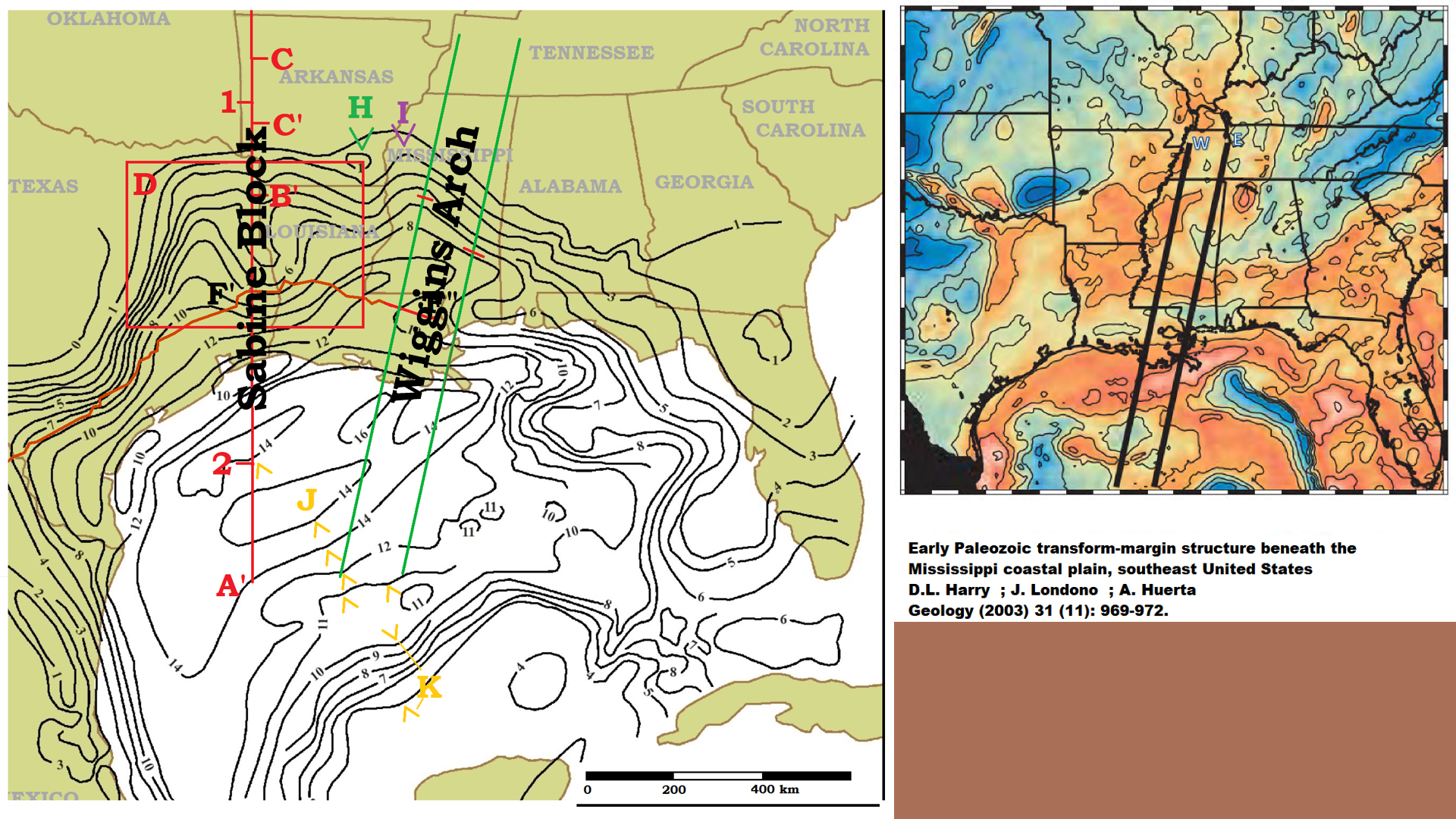

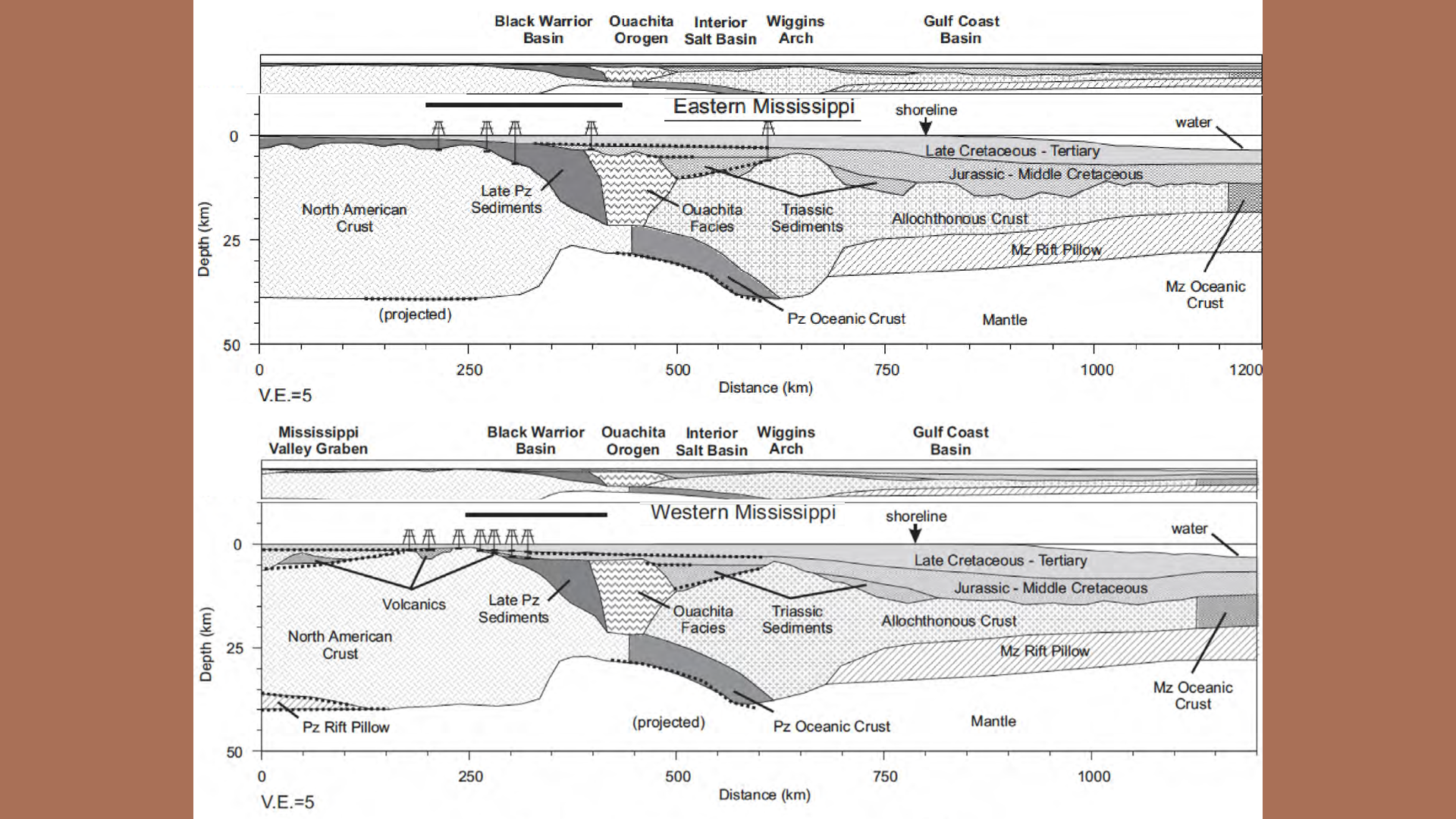

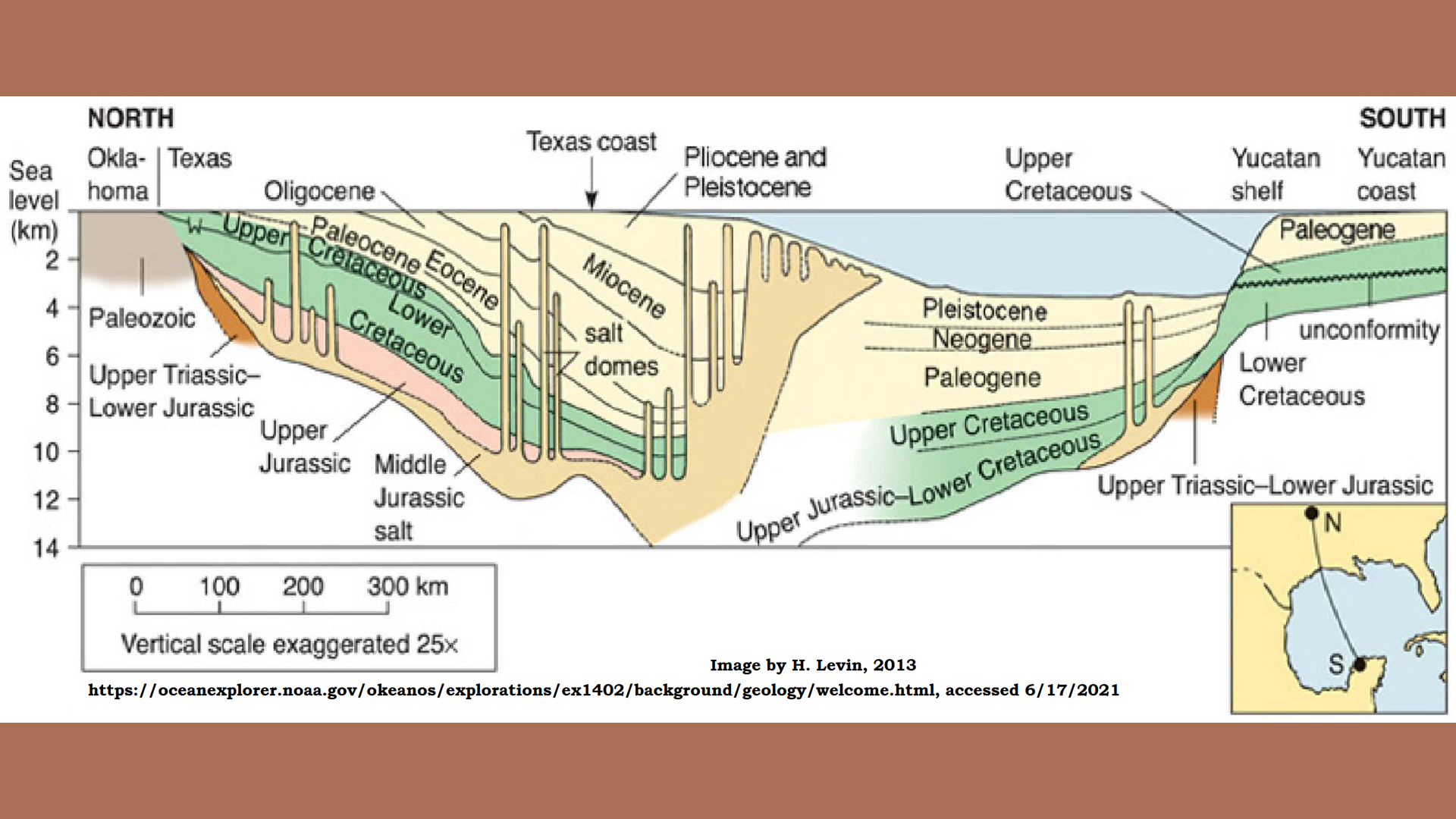

Figure 64: (A) One map of Butte Fault that may have been taken from an old map or estimated from the terrane. I highlighted their designation of Butte Fault as two linears using corresponding labels to Figure 66. (B) Linears I located in the area using topographic clues, CGRS in white and short concentric linears shown in red. Labels as in Figure 65. Figure 65: Craters found to correlate with linears around (A) Butte Fault and (B) Bright Angel-Phantom Creek-Eminence Break Fault. Butte Fault is up to east and Davidson, Molokai, and Salsipuedes craters all center in the Pacific Ocean. Red oval encircles a topographic high parallel to Ipojuca linear (Chapter 15A). The Ipojuca linear extends through Nankoweep Butte, Figure 62B. Ipojuca center is in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Huntoon and Sears identified the Bright Angel Fault as a normal fault (compensation fault) with west side up, meaning its center is to the southeast. I correlate it with the Gulf of Mexico crater. Additionally, they identify it as faulting between the deposition of the Unkar and Chuar Groups. This means that the Gulf of Mexico crater arrived between the Tatanka and Gorda craters. But in fact, the Gulf of Mexico is east of the Tatanka and would arrive first, but its CGRS may not have arrived here until after the Tatanka’s CGRS. This type of associations allow sequence and timing to be established for craters outside of the Grand Canyon.

Figure 65: Craters found to correlate with linears around (A) Butte Fault and (B) Bright Angel-Phantom Creek-Eminence Break Fault. Butte Fault is up to east and Davidson, Molokai, and Salsipuedes craters all center in the Pacific Ocean. Red oval encircles a topographic high parallel to Ipojuca linear (Chapter 15A). The Ipojuca linear extends through Nankoweep Butte, Figure 62B. Ipojuca center is in the southern Atlantic Ocean. Huntoon and Sears identified the Bright Angel Fault as a normal fault (compensation fault) with west side up, meaning its center is to the southeast. I correlate it with the Gulf of Mexico crater. Additionally, they identify it as faulting between the deposition of the Unkar and Chuar Groups. This means that the Gulf of Mexico crater arrived between the Tatanka and Gorda craters. But in fact, the Gulf of Mexico is east of the Tatanka and would arrive first, but its CGRS may not have arrived here until after the Tatanka’s CGRS. This type of associations allow sequence and timing to be established for craters outside of the Grand Canyon. Figure 66: Top of the Crystalline Basement under the Grand Canyon and some of the earliest mapped faults (Precambrian). Butte Fault designated in blue as separate linears: (A) CGRS from Molokai crater, (B) CGRS from Salsipuedes crater, (C) CGRS again from Molokai crater, (D) CGRS again from Salsipuedes crater, and (E) CGRS from Ipojuca crater. Bright Angel-Phantom Creek-Eminence Break Fault designated in red. Two portions of the more southerly Mesa Butte Fault also appear to correspond with CGRS from the Gulf of Mexico crater. Faults are often made up of segments from different shear centers that have become associated in the mind of the geologist because they seem to form a continuous line on the ground. This reflects the observation in the Paradox Basin, made by Gay (2012) that faults and other structures exhibit “straight line segments with corners” where they meet other segments. They are largely not one continuous linear.

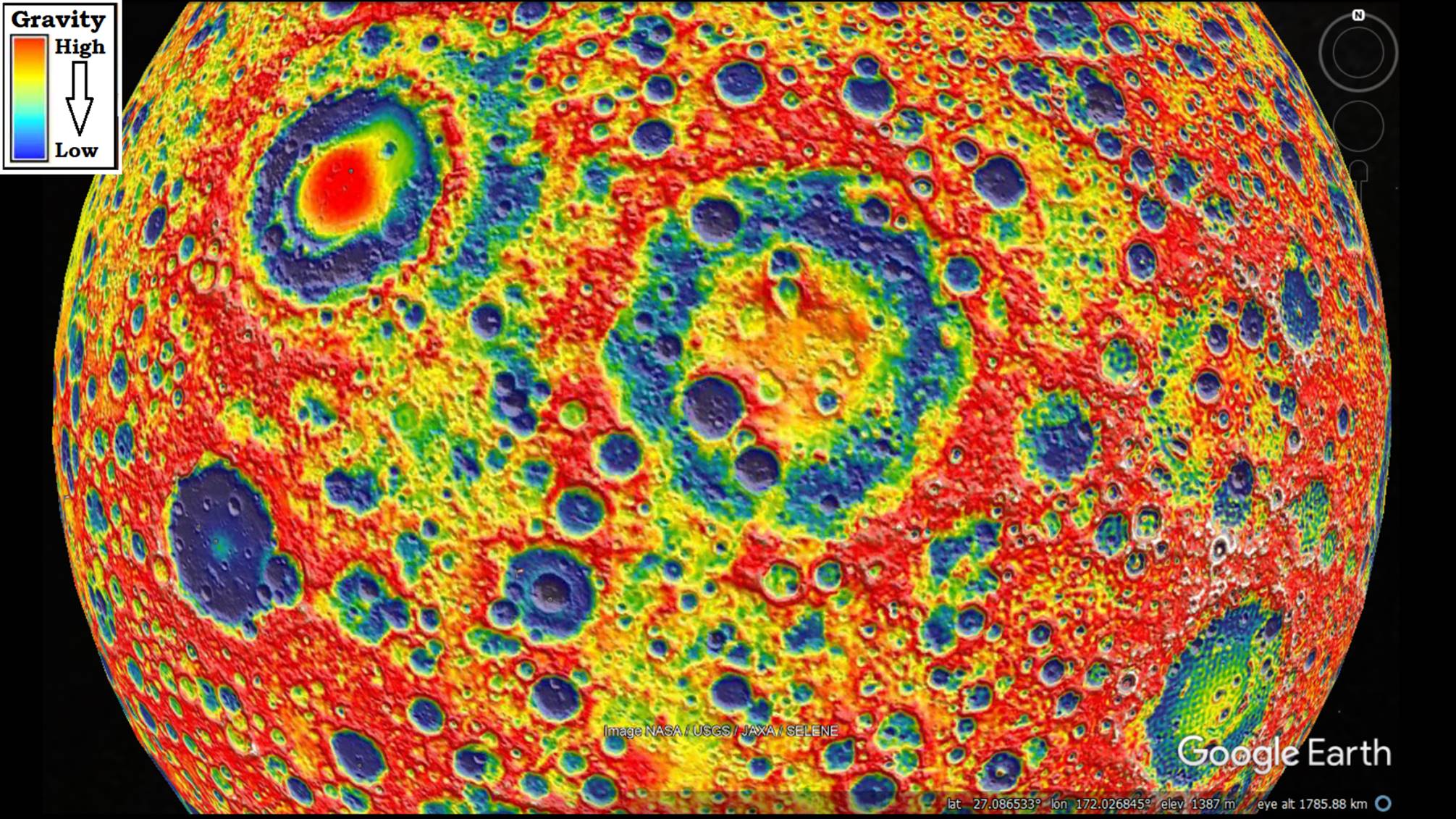

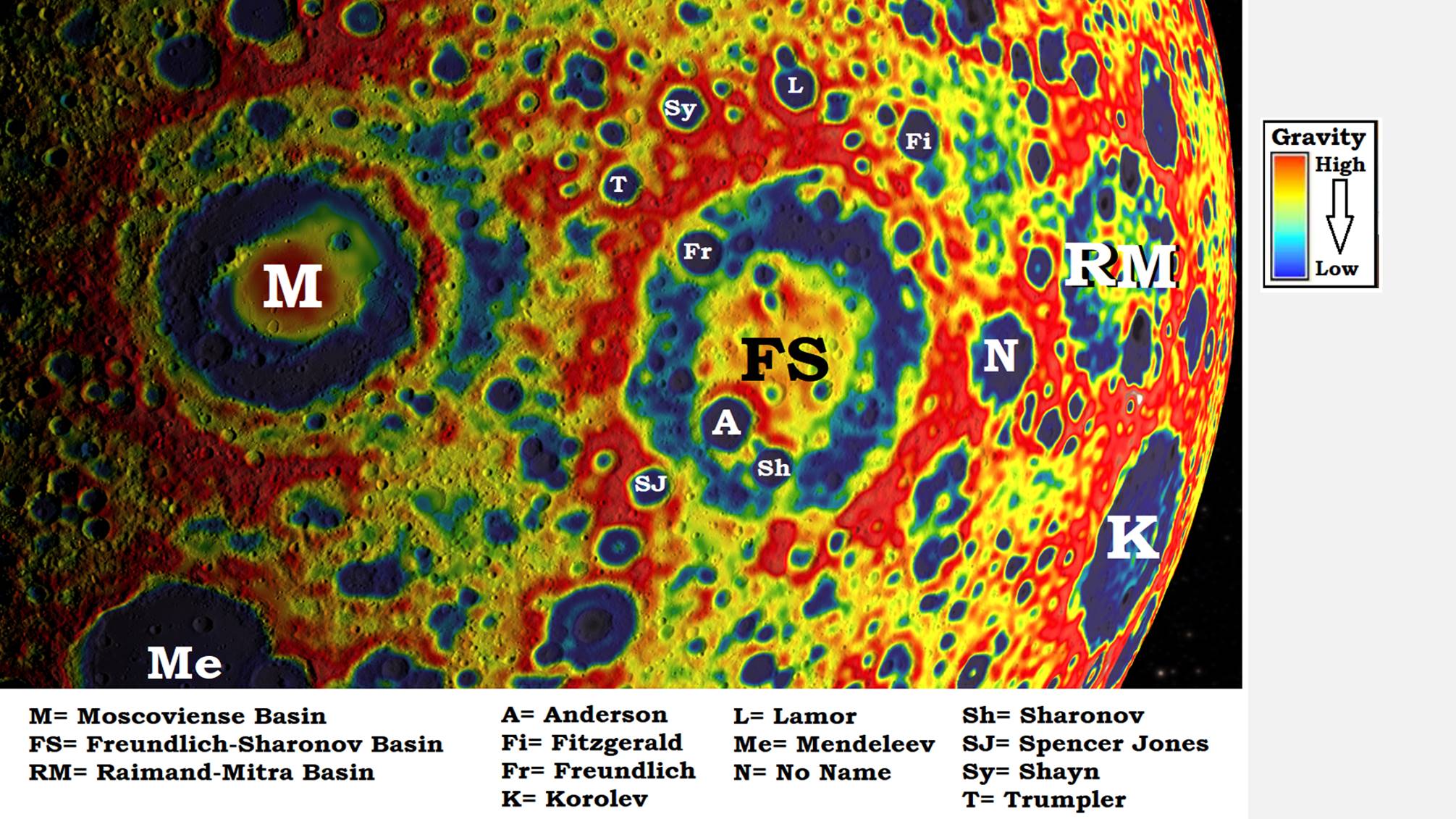

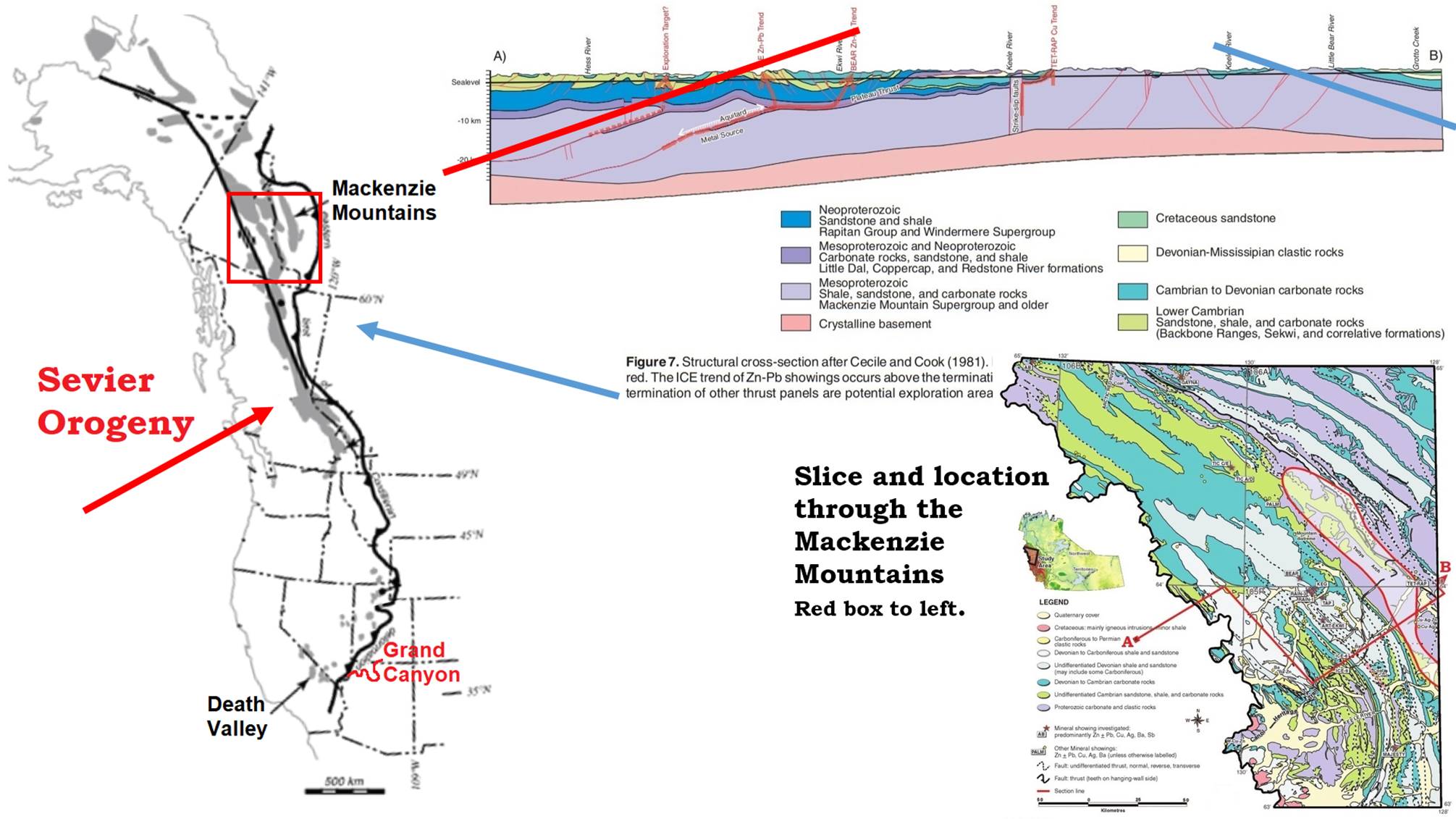

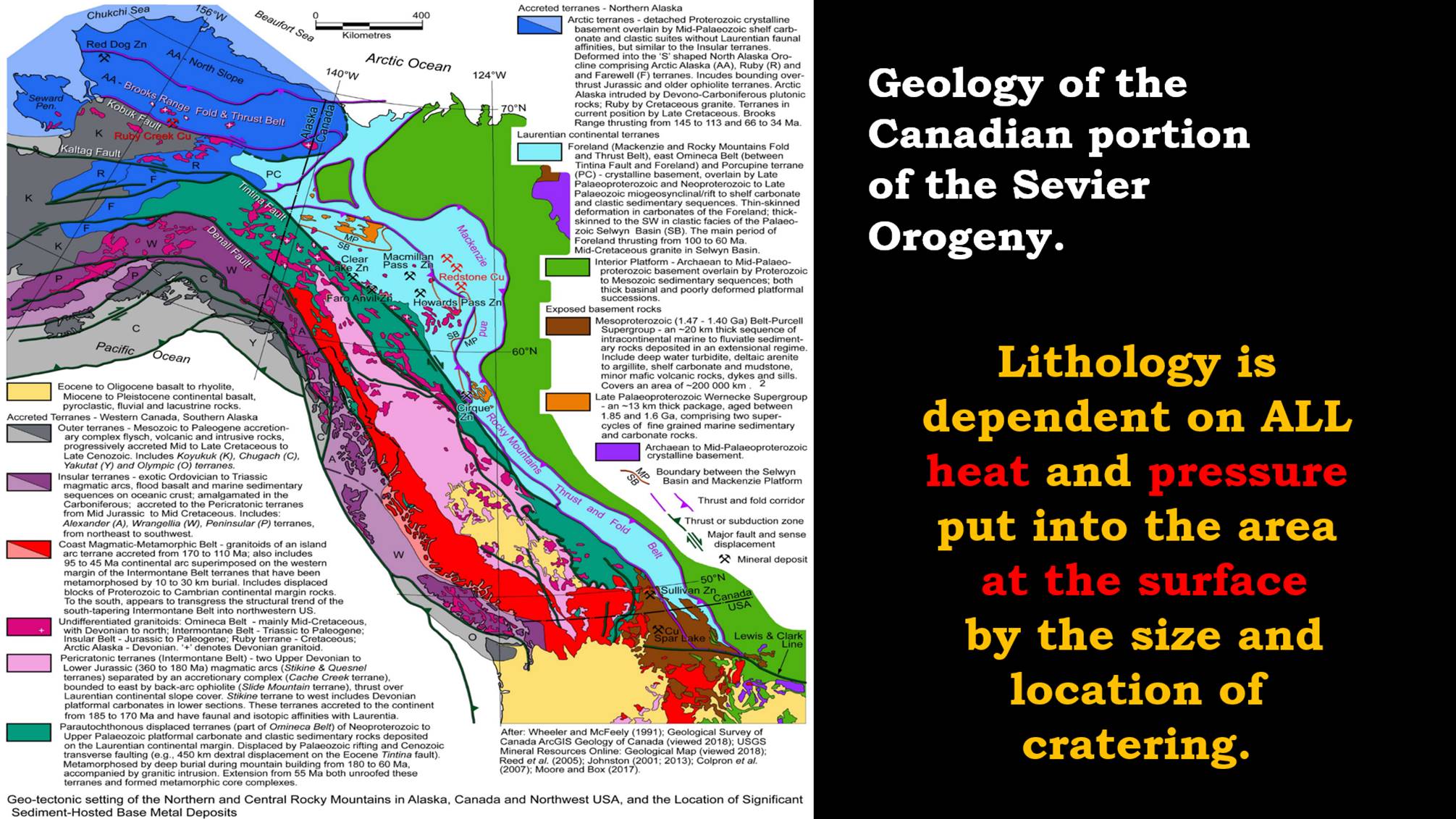

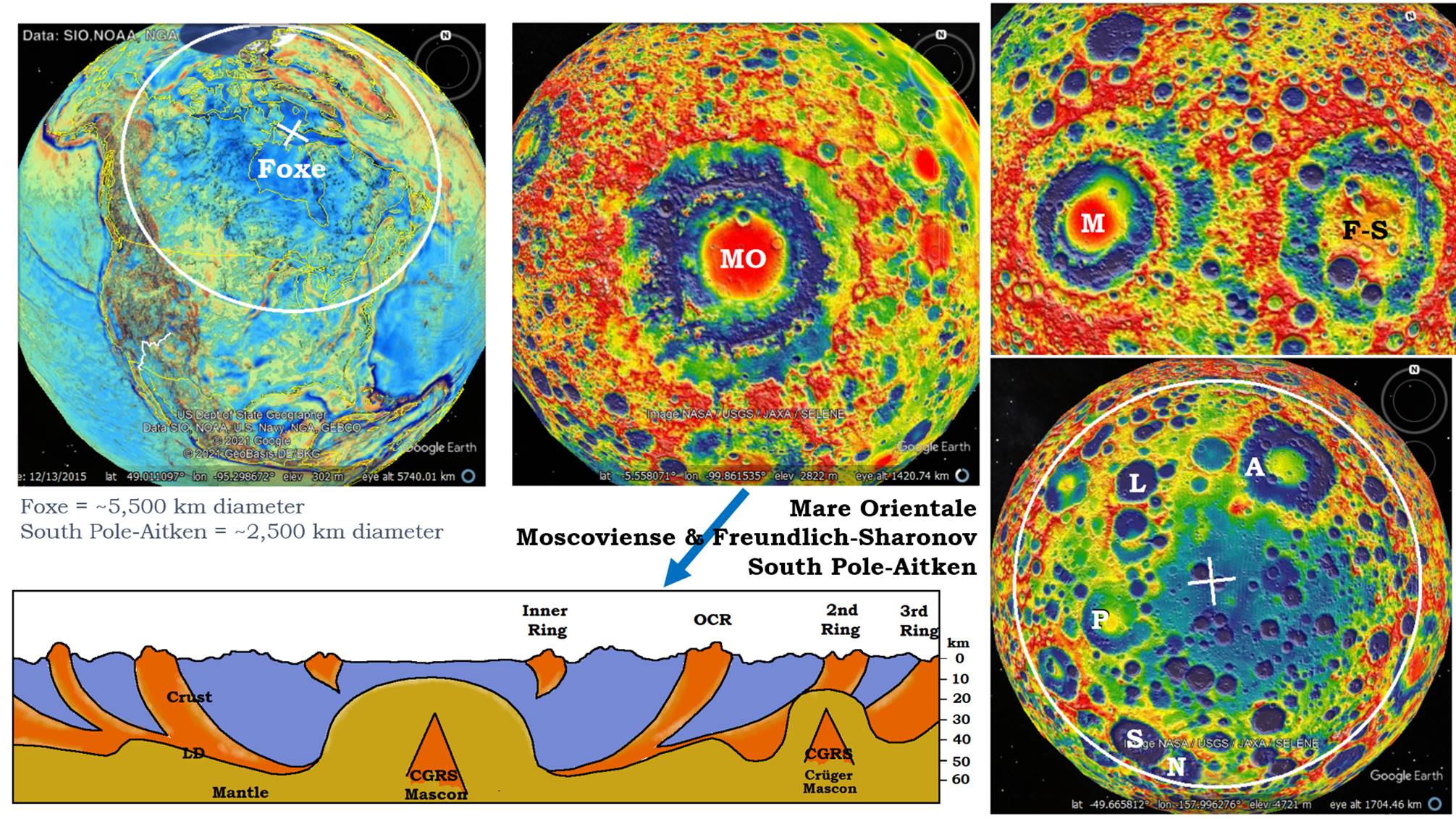

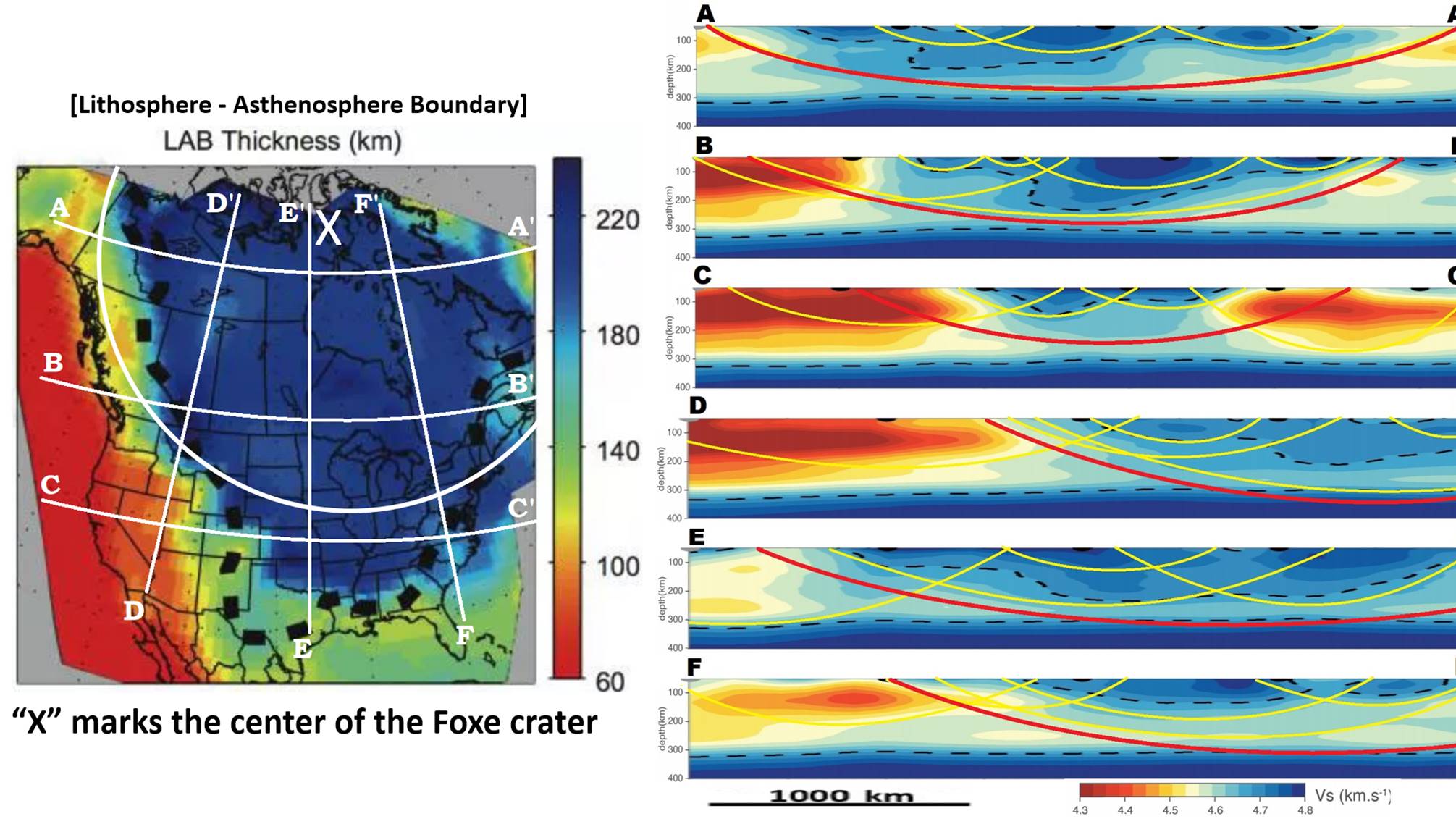

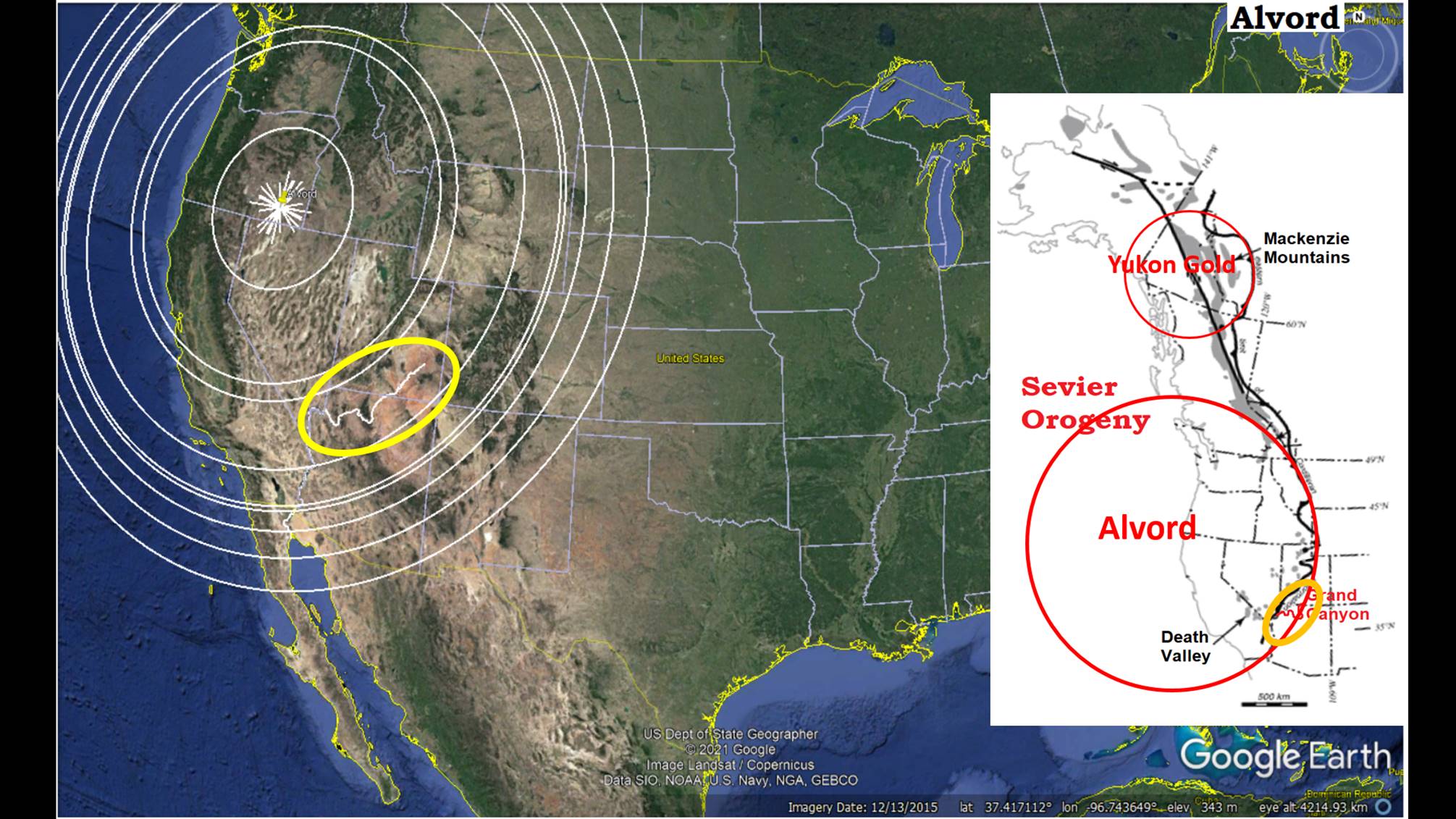

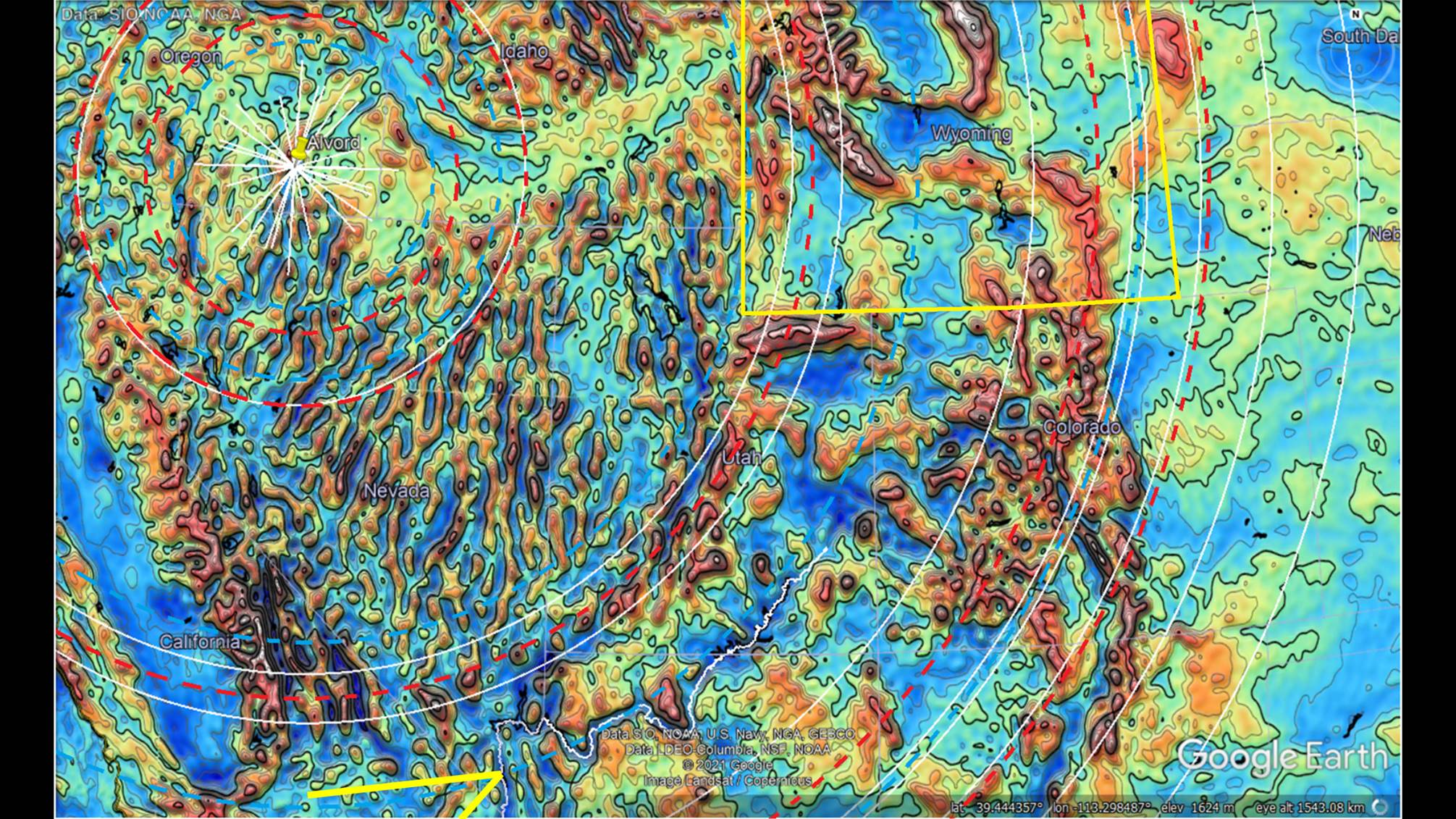

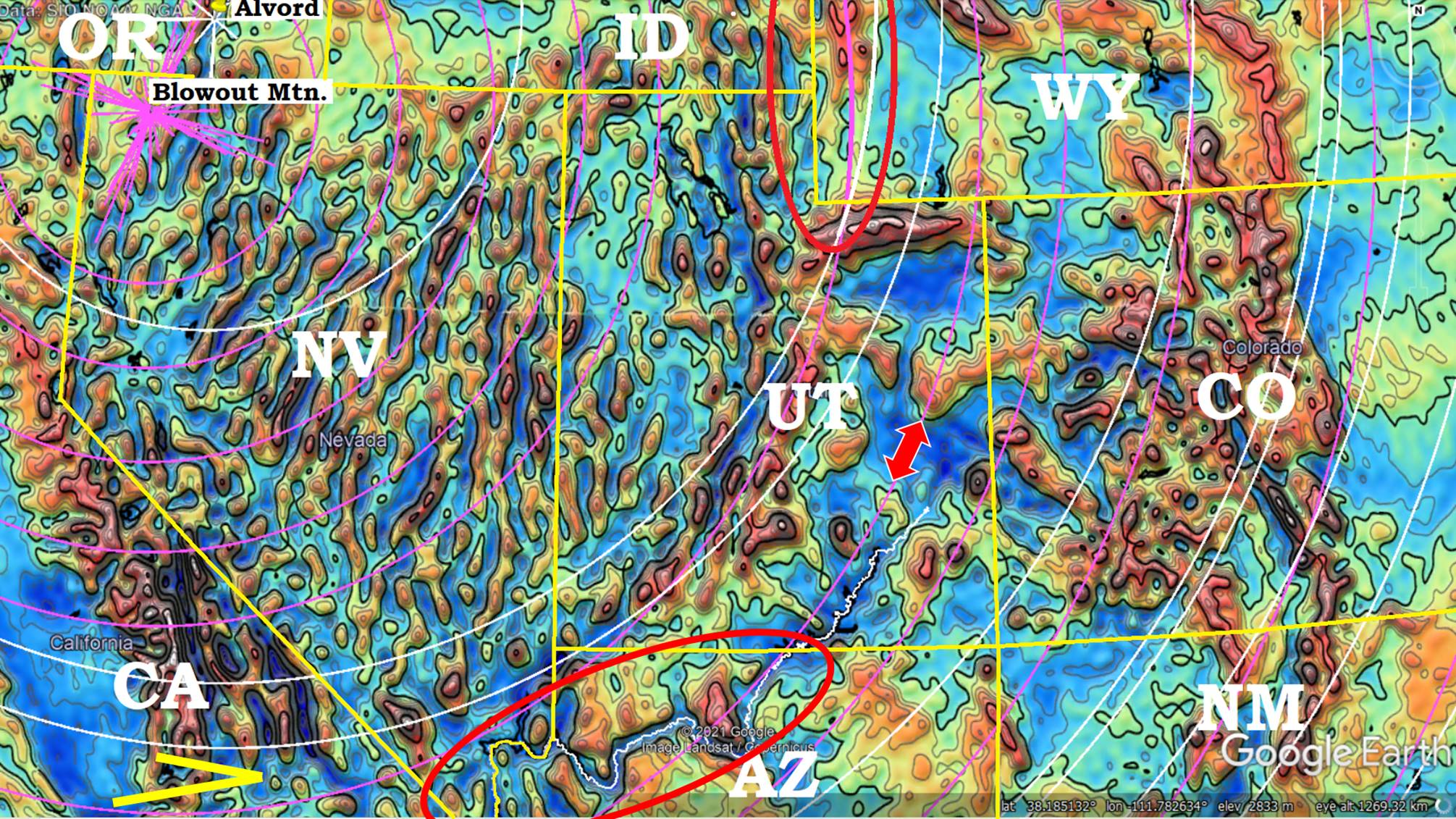

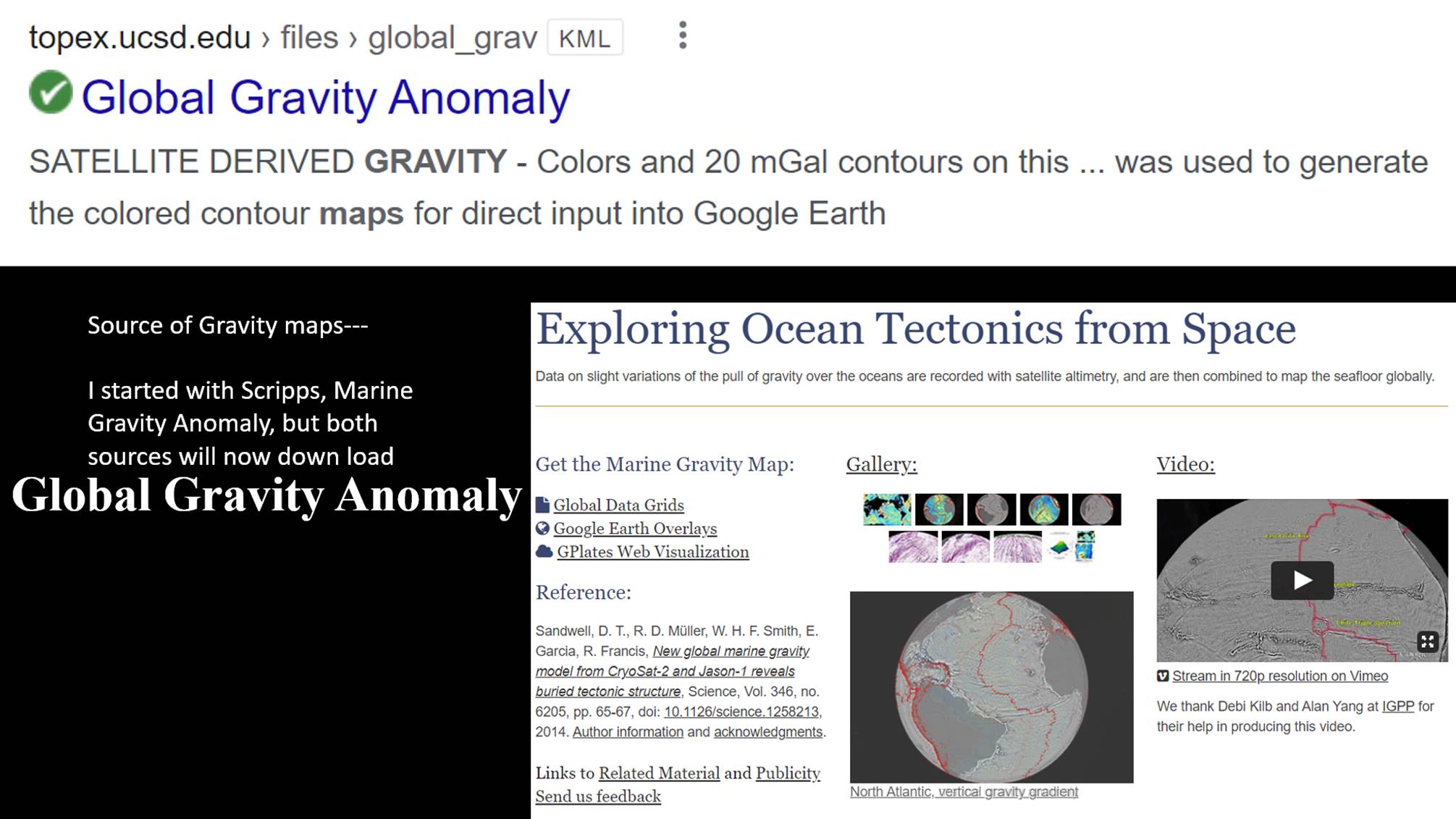

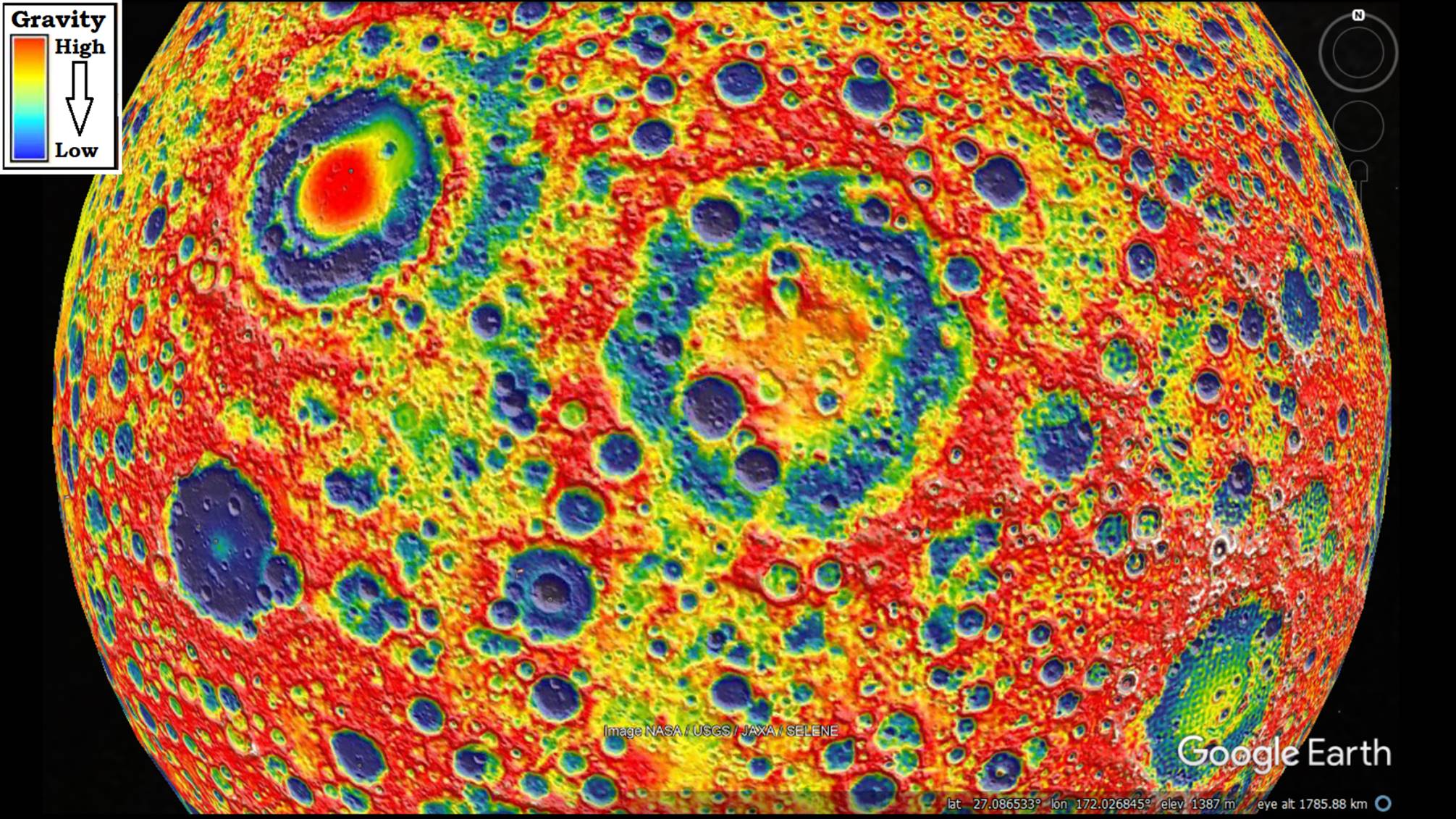

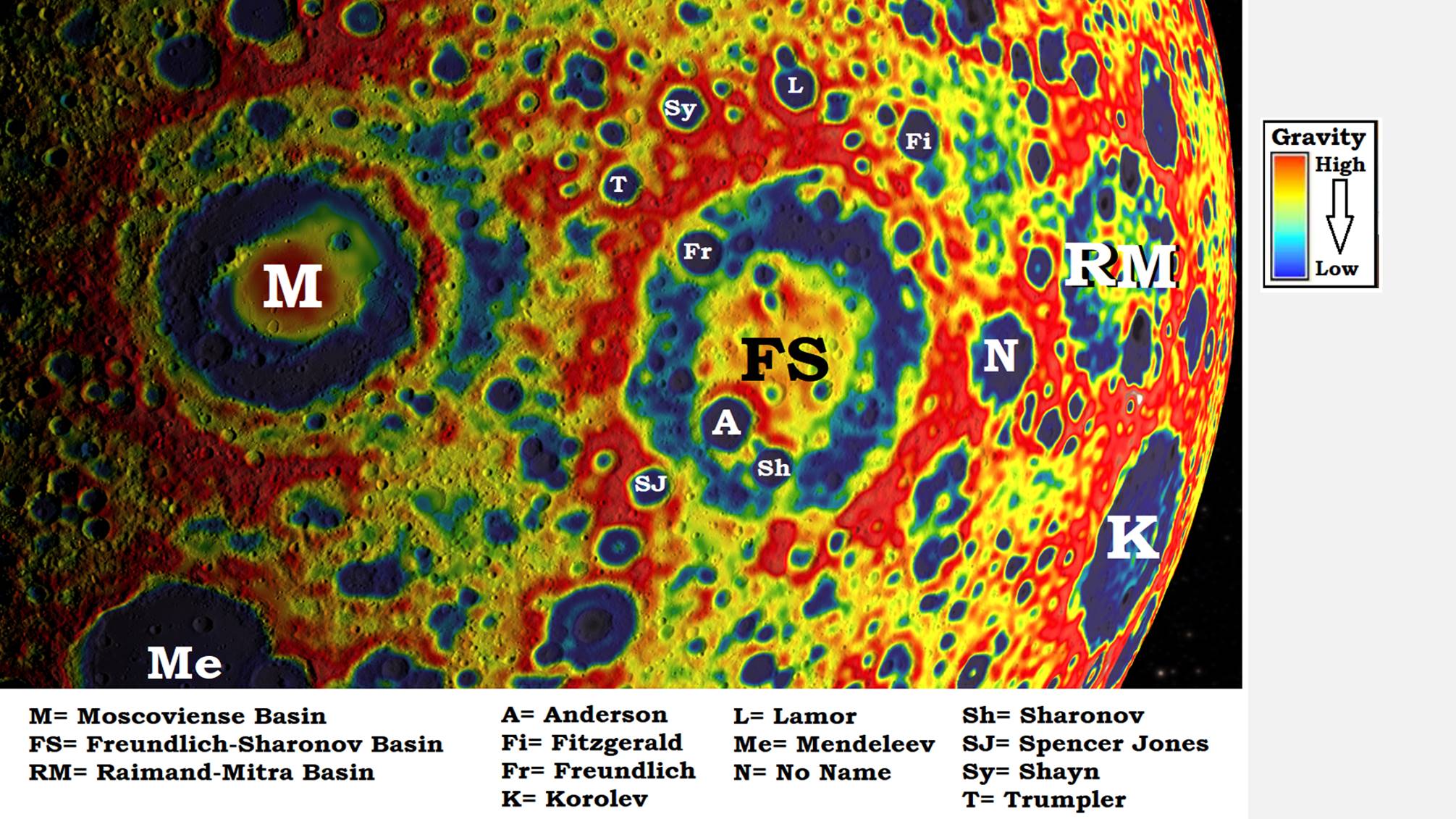

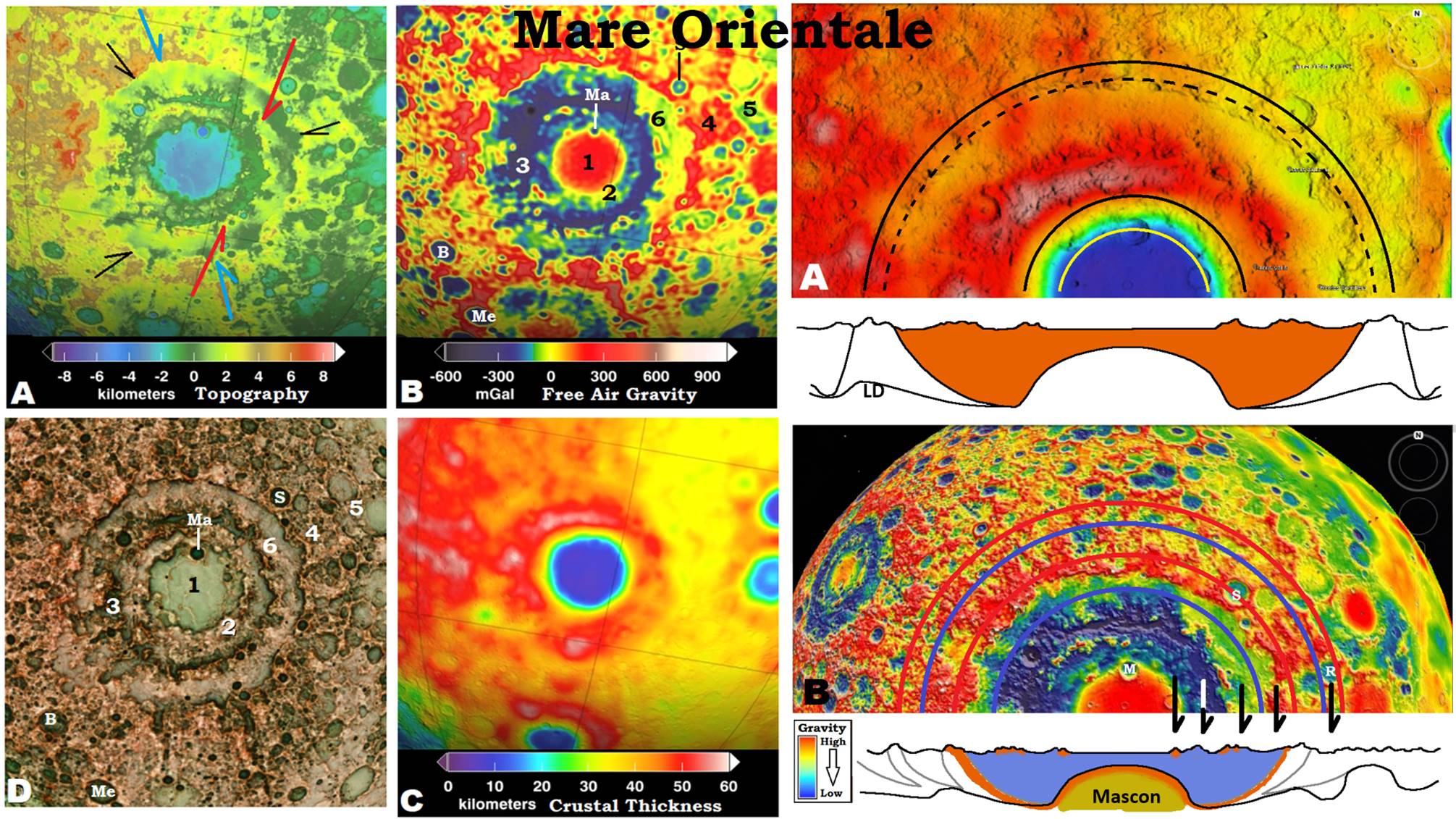

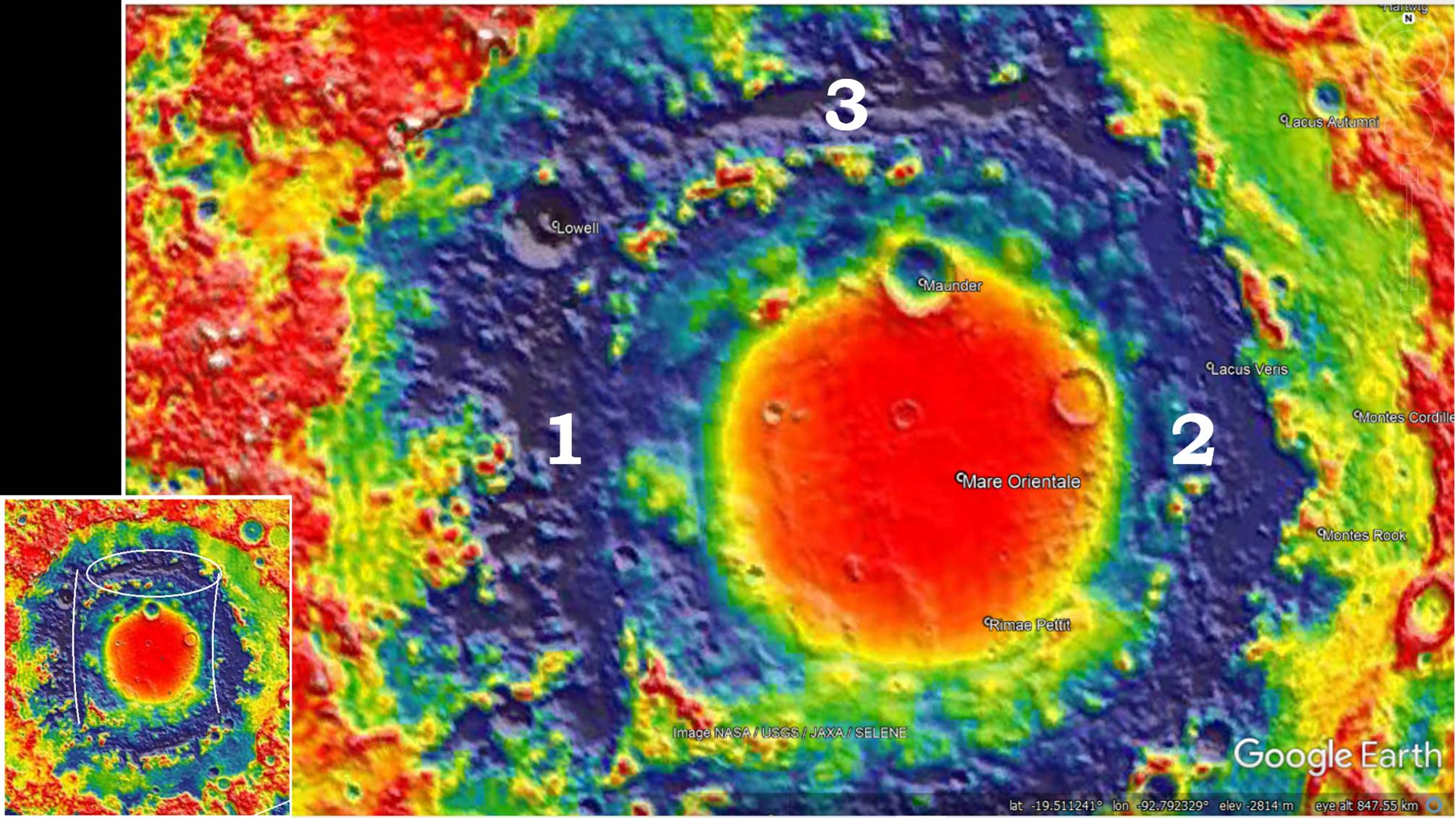

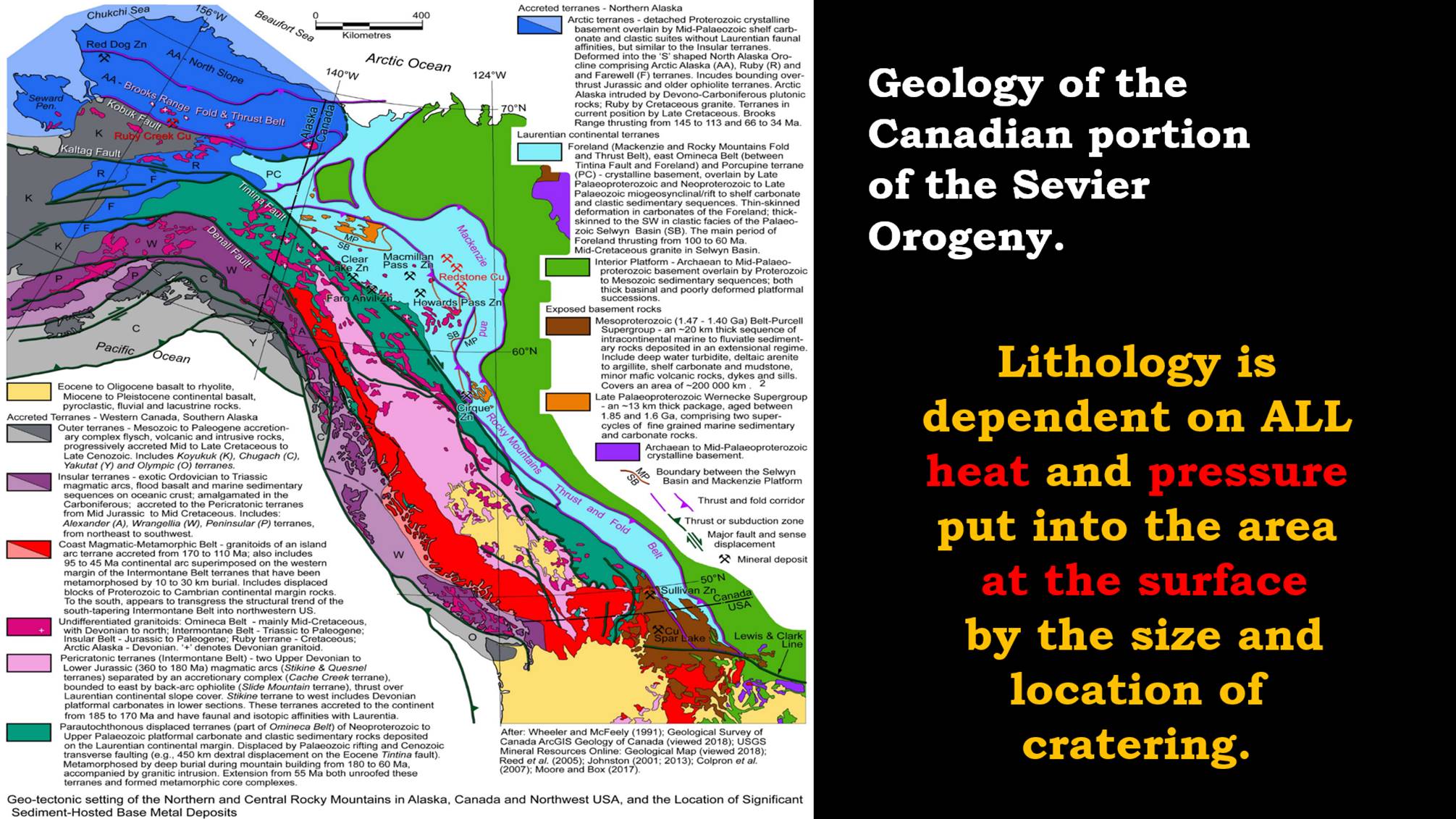

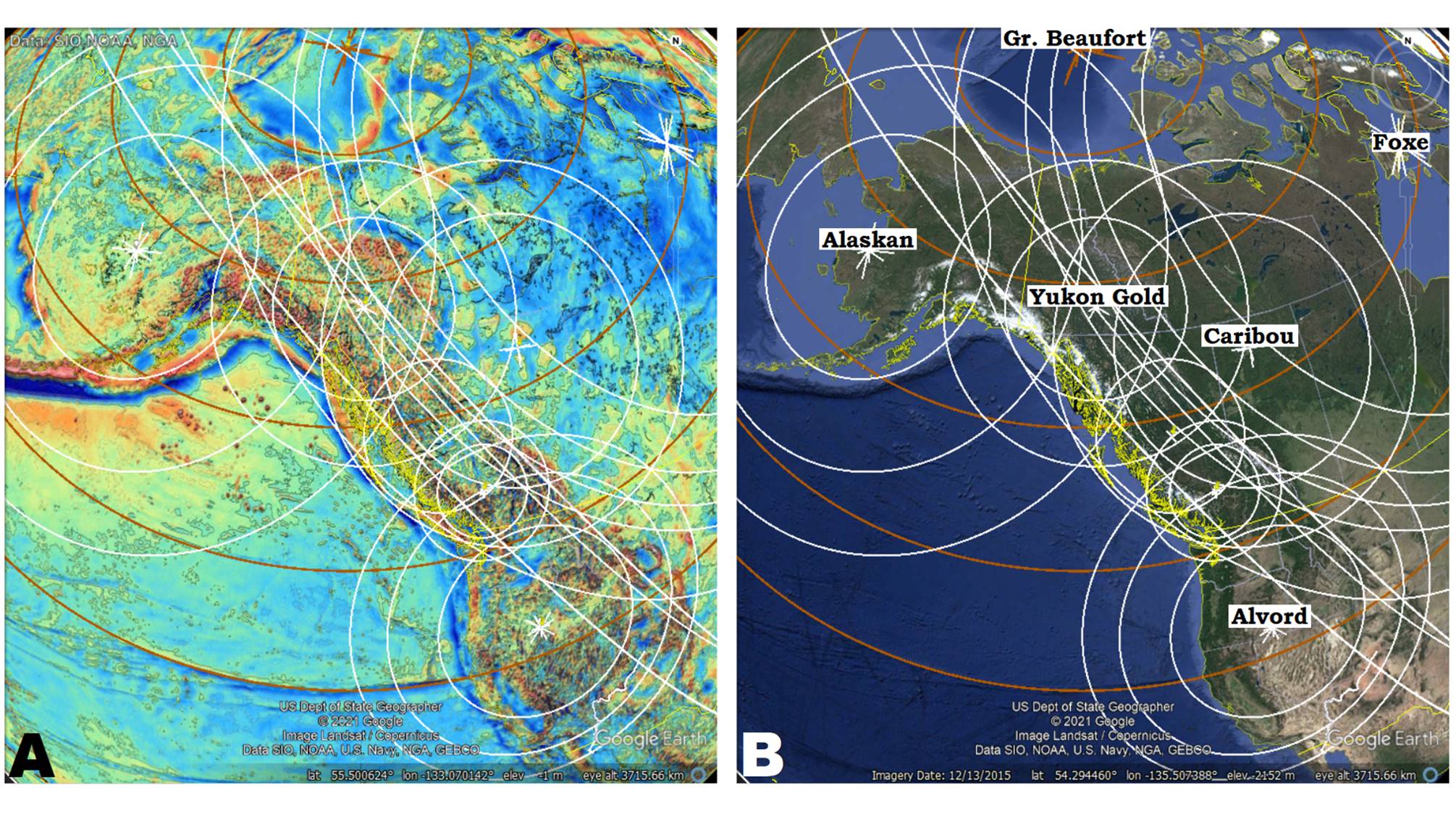

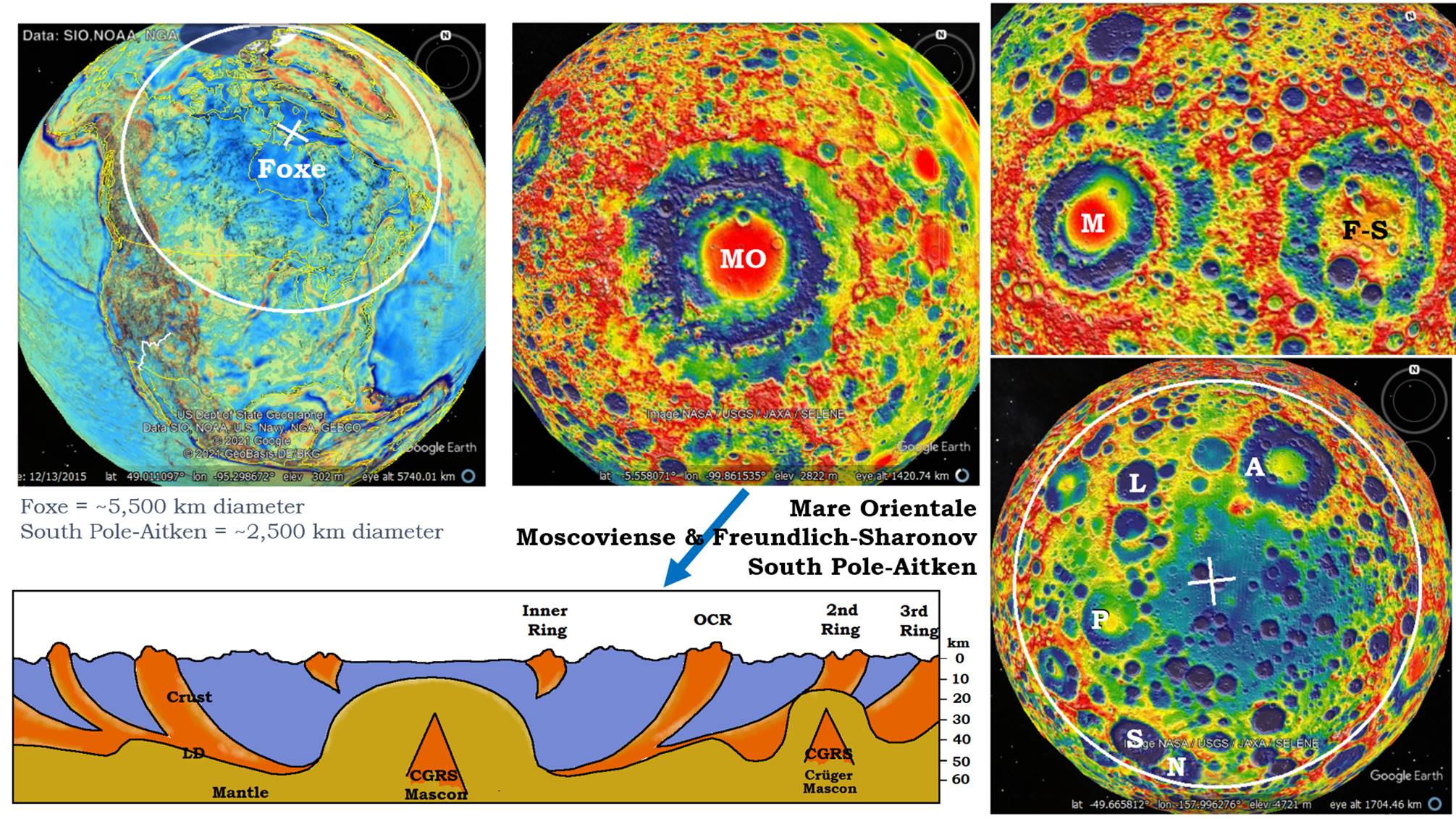

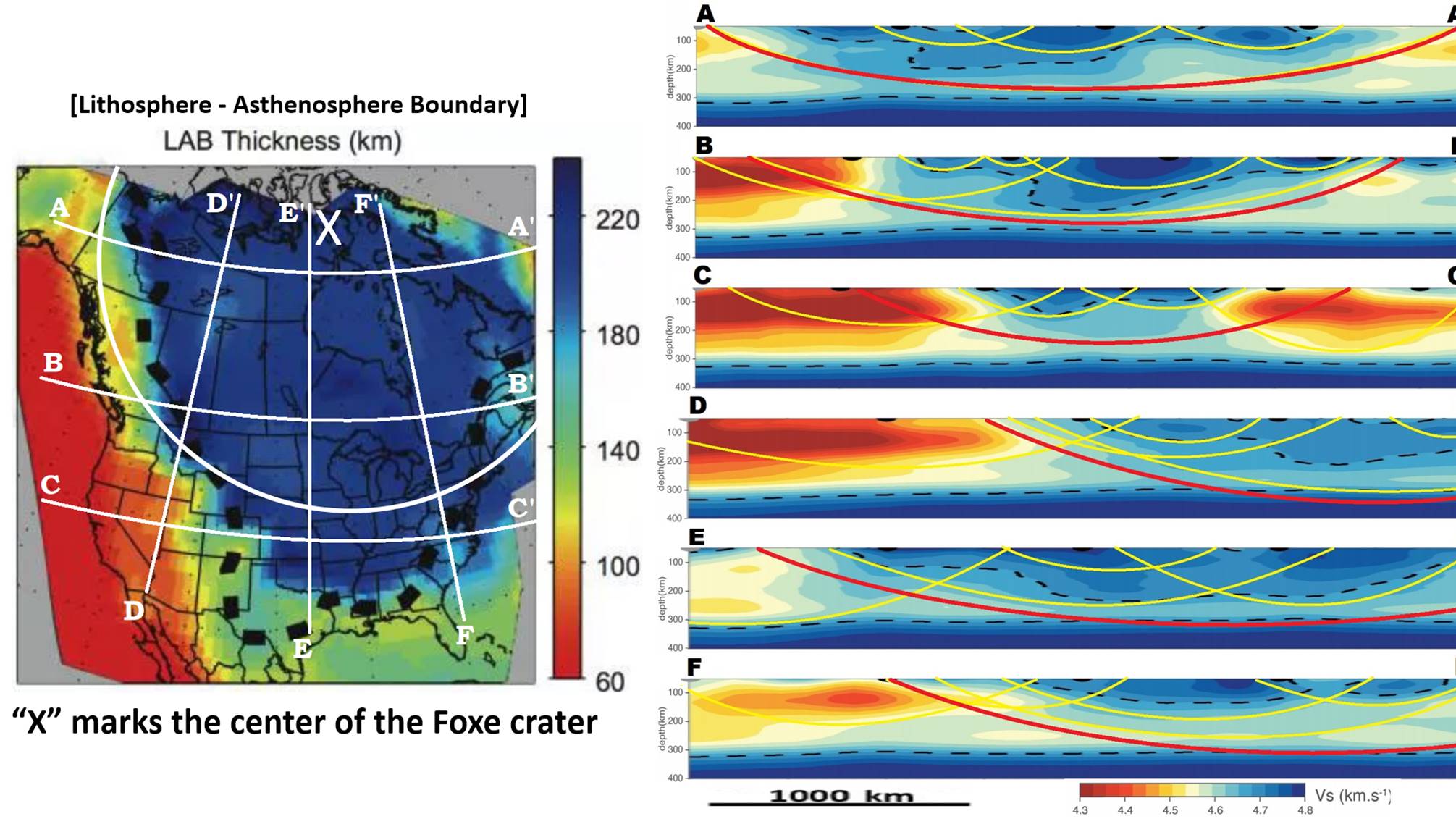

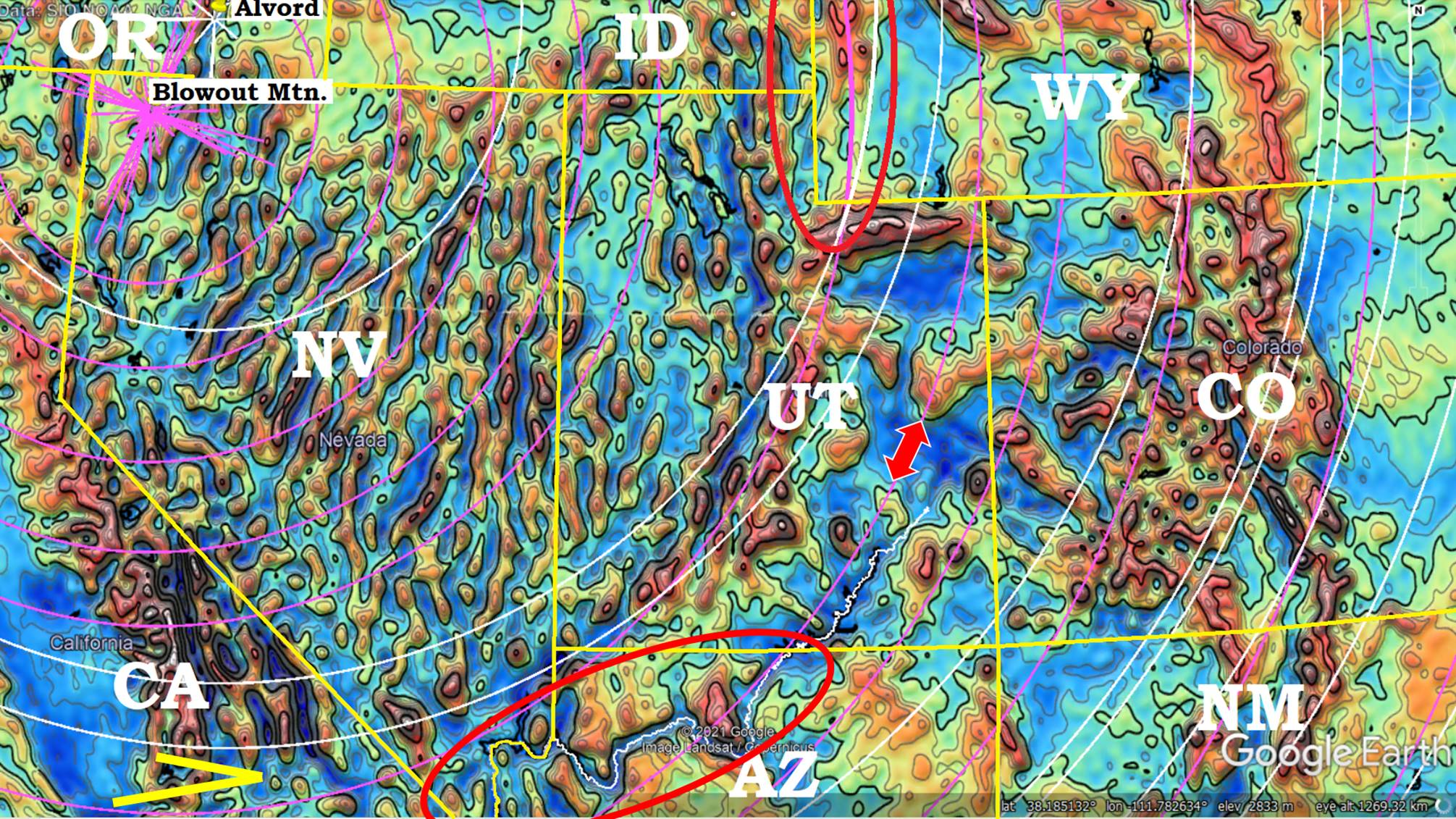

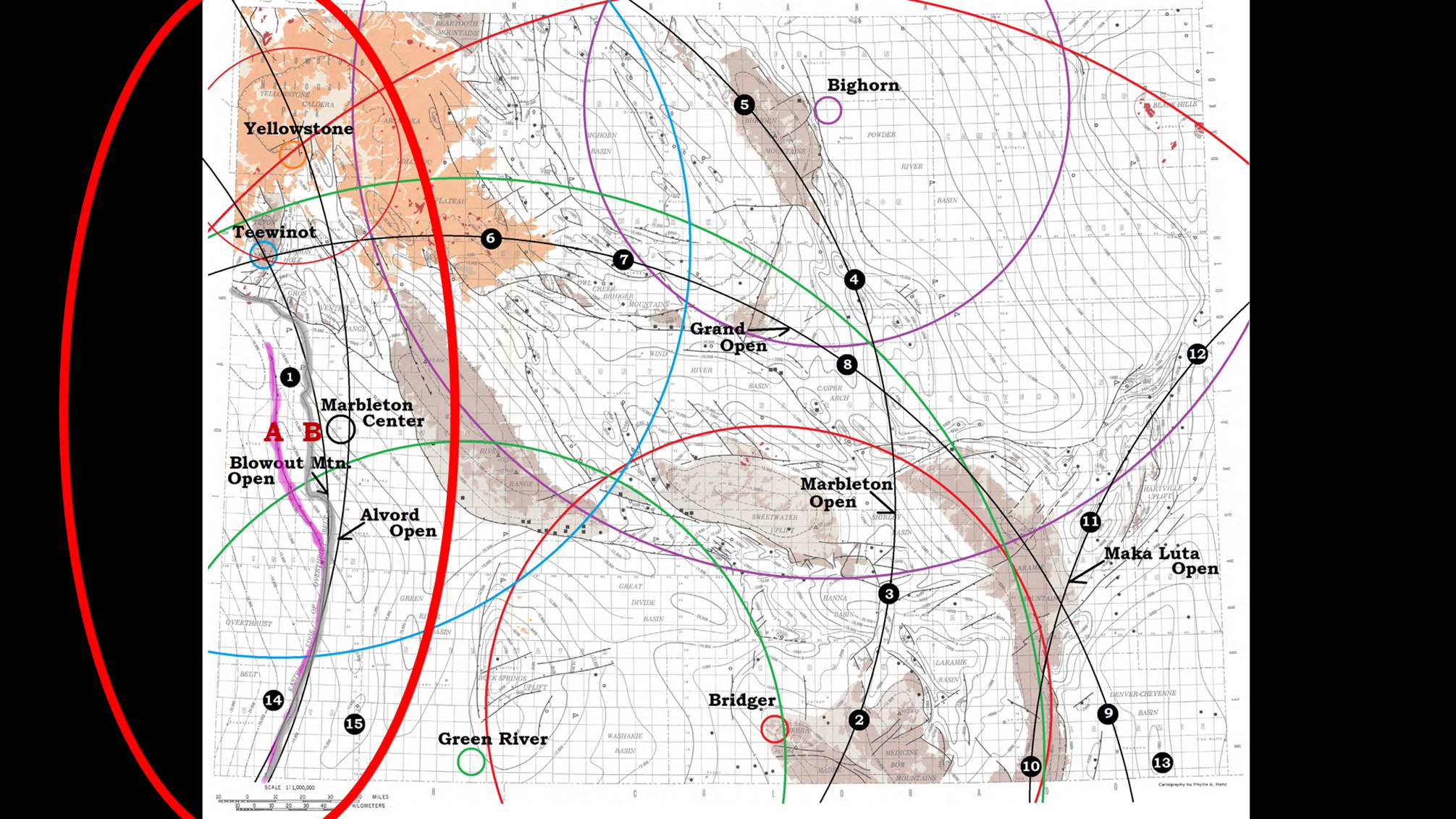

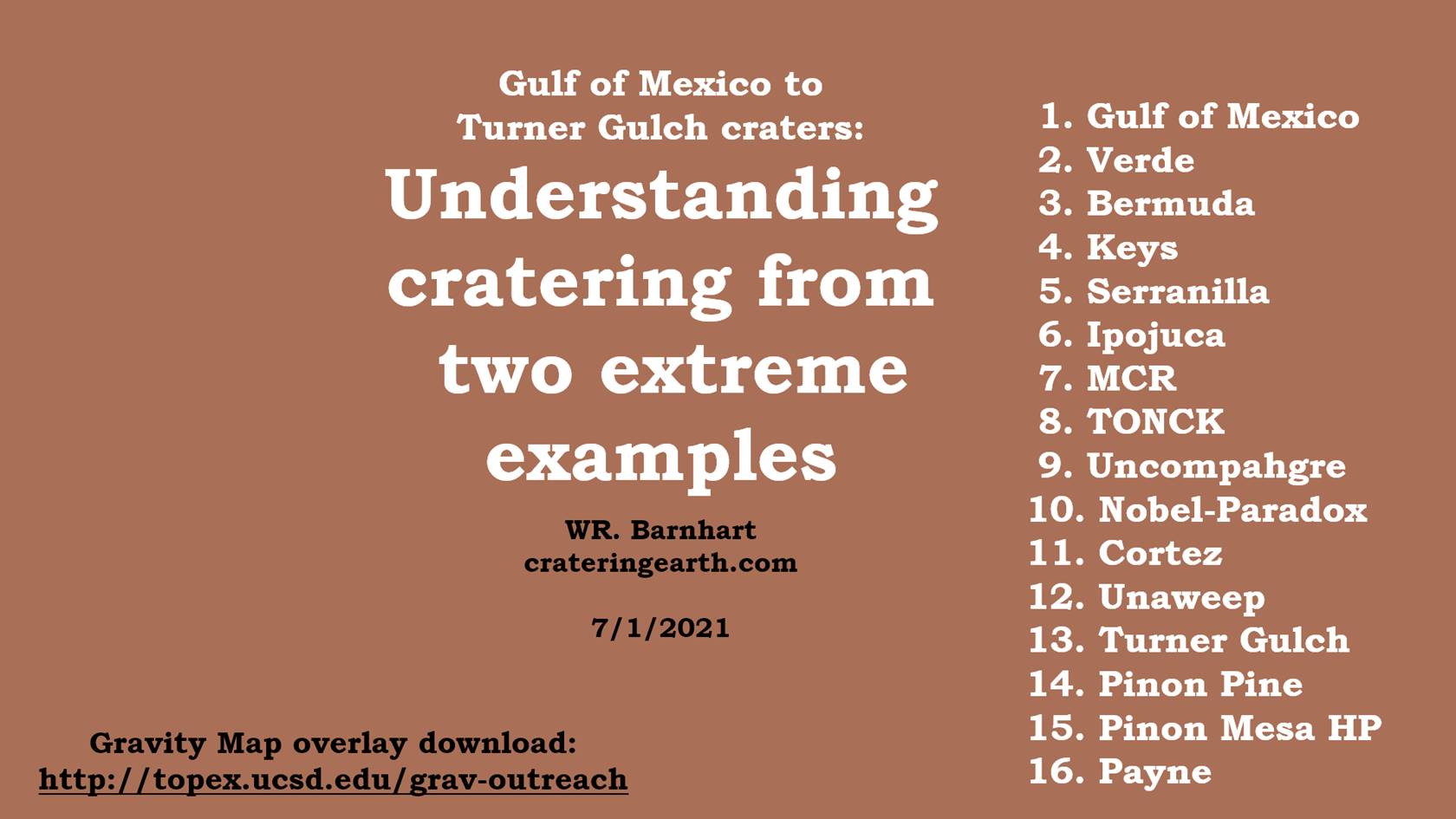

Figure 66: Top of the Crystalline Basement under the Grand Canyon and some of the earliest mapped faults (Precambrian). Butte Fault designated in blue as separate linears: (A) CGRS from Molokai crater, (B) CGRS from Salsipuedes crater, (C) CGRS again from Molokai crater, (D) CGRS again from Salsipuedes crater, and (E) CGRS from Ipojuca crater. Bright Angel-Phantom Creek-Eminence Break Fault designated in red. Two portions of the more southerly Mesa Butte Fault also appear to correspond with CGRS from the Gulf of Mexico crater. Faults are often made up of segments from different shear centers that have become associated in the mind of the geologist because they seem to form a continuous line on the ground. This reflects the observation in the Paradox Basin, made by Gay (2012) that faults and other structures exhibit “straight line segments with corners” where they meet other segments. They are largely not one continuous linear. Figure 67: What do the Sevier Orogeny and the Alvord crater have to do with what we can now see in the Grand Canyon? Remember the Gravity Map of the farside of the moon? The distinct bull’s-eye appearance of high and low, red and blue, gravity? If cratering did this to the moon, it also did this to the earth. In spite of all the later cratering, we can see that the Grand Canyon (red oval) lays in a broad blue band that extends well beyond the canyon. If it is dark blue, it was filled with a less dense version of the rock. As I have suggested the Alvord crater deposited the Chuar Formation, so that formation in this area is less dense than the alternative. If that formation is less dense, it will be preferentially eroded by the adiabatic conversion forming release valleys in subsequent cratering. What are some of these larger subsequent craters, and what did they each contribute???

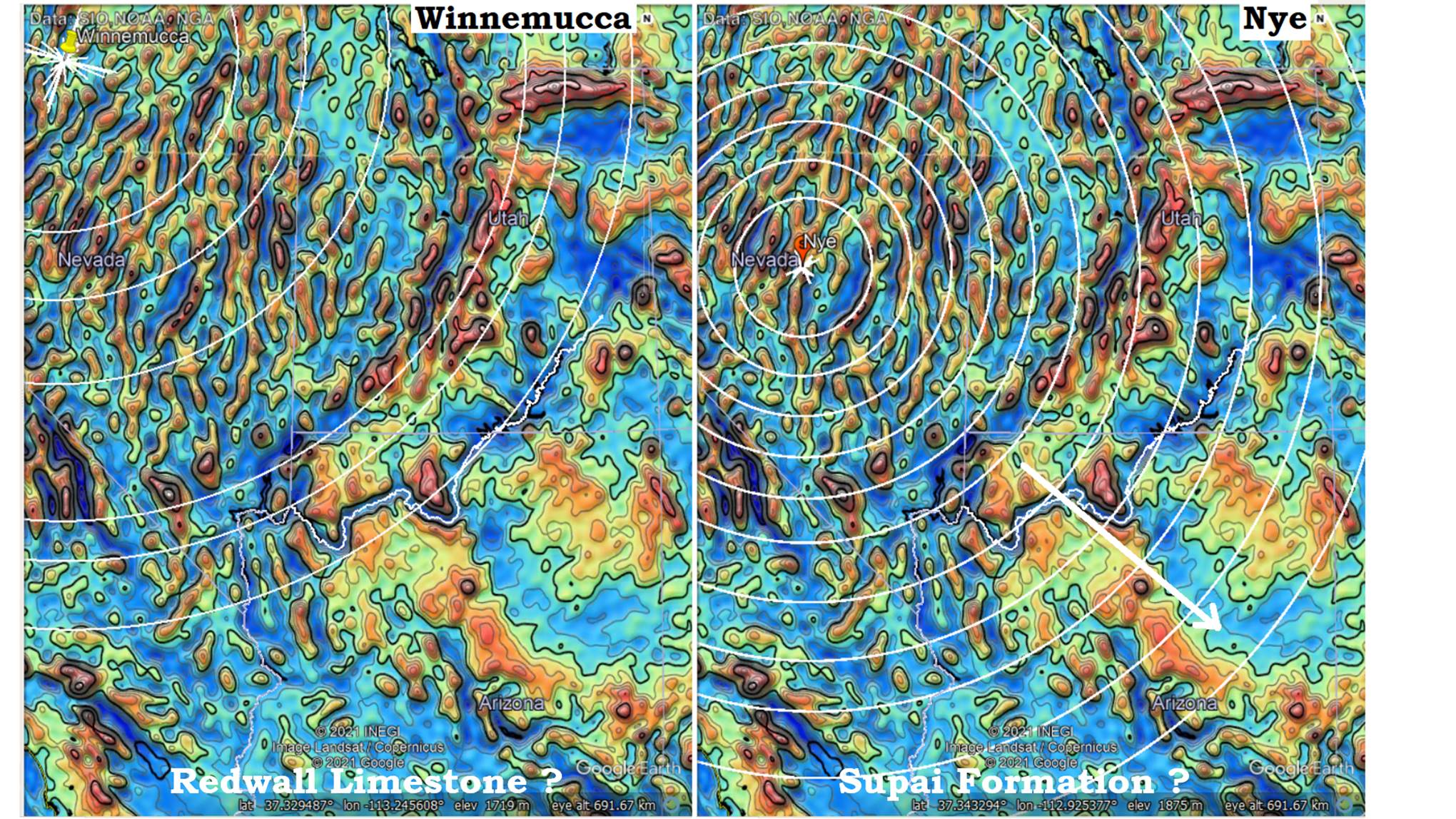

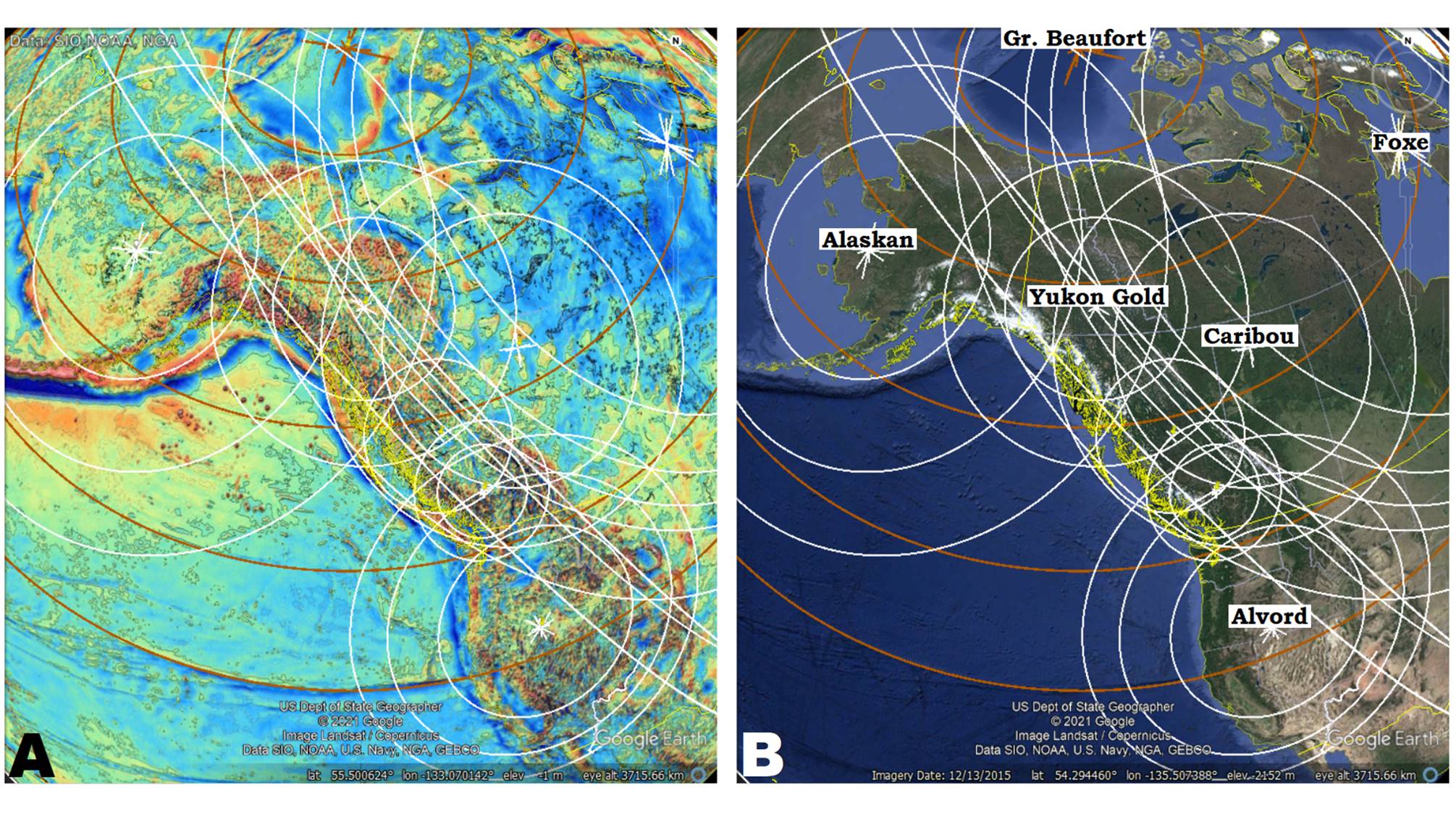

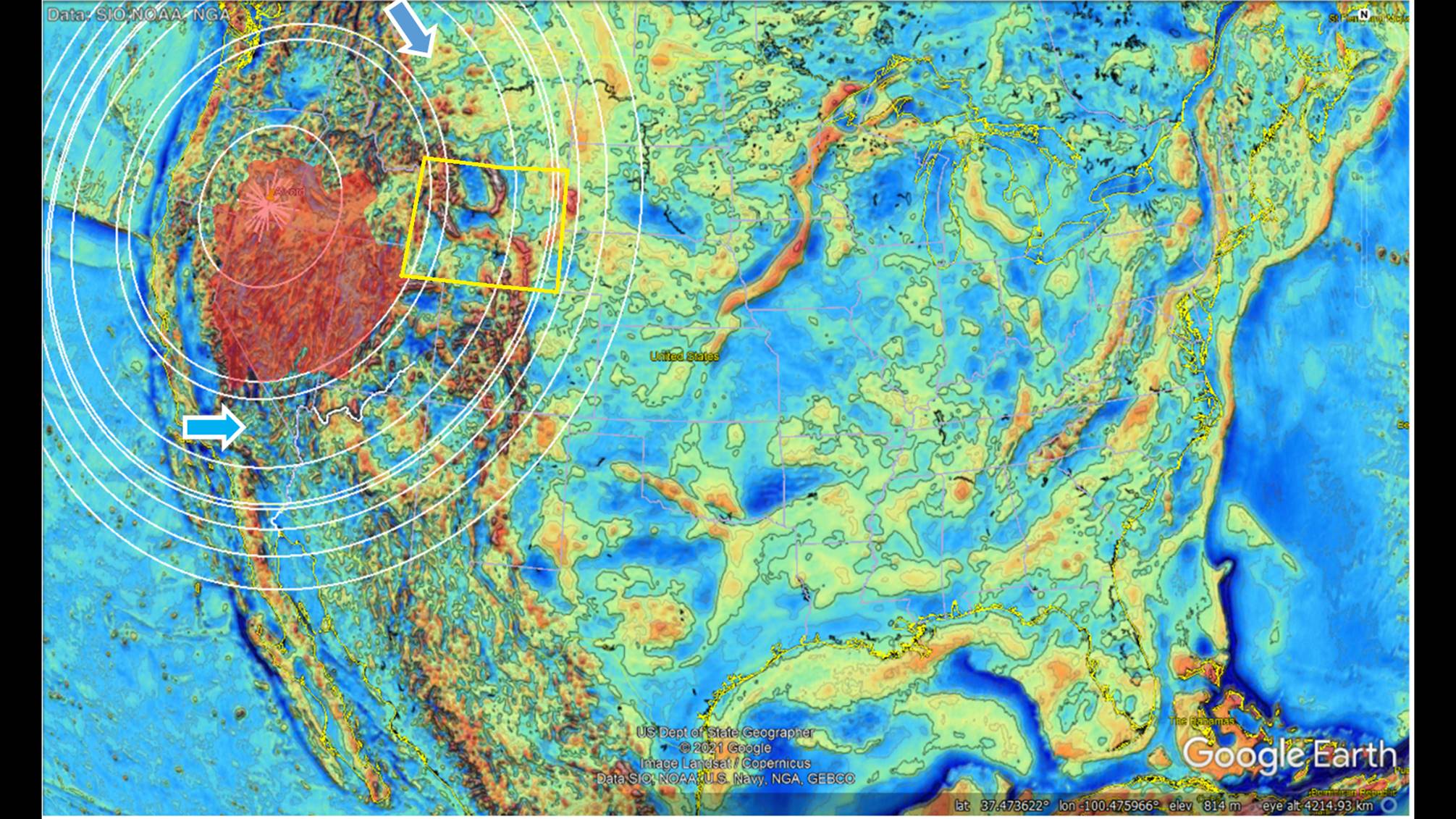

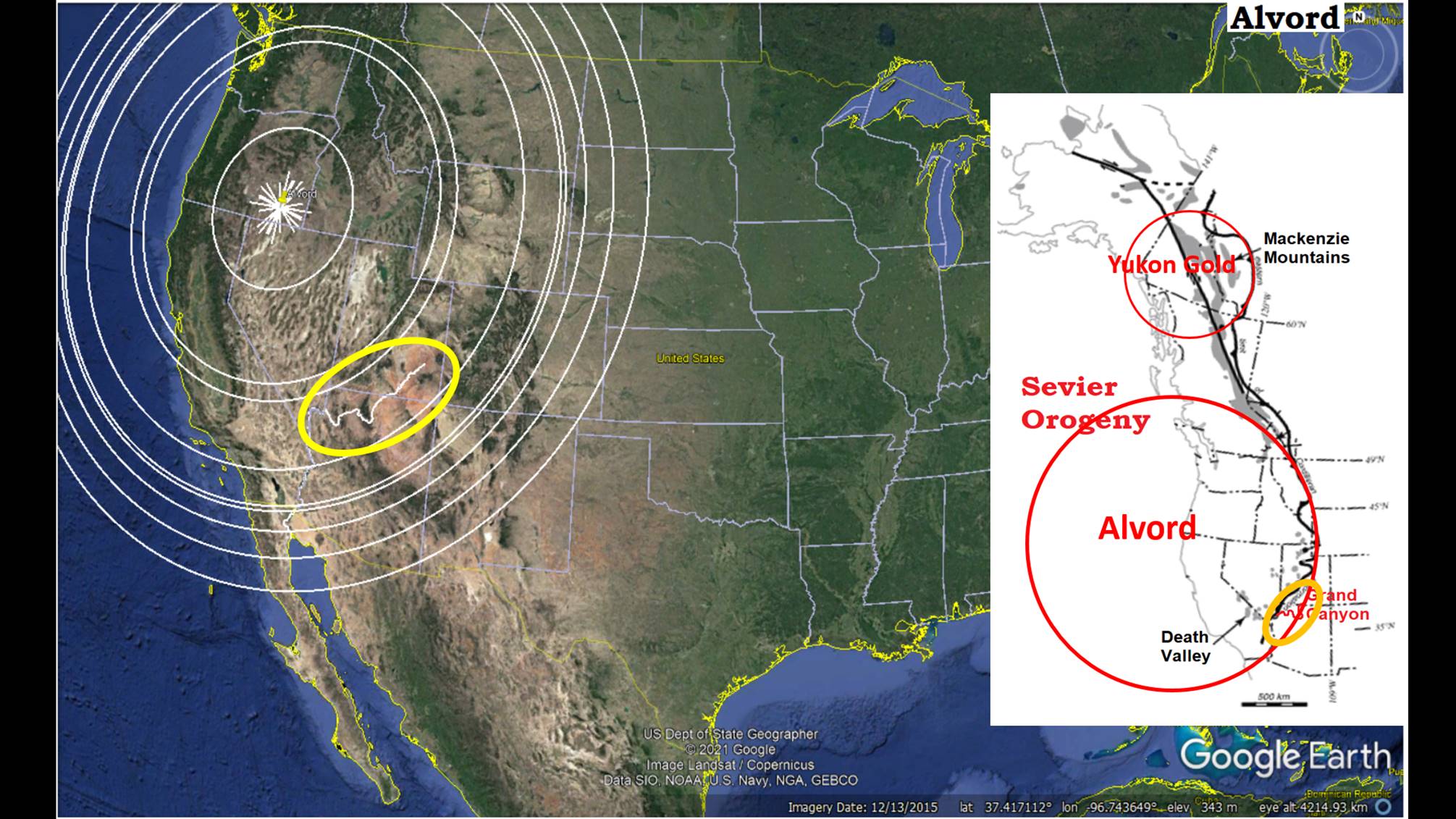

Figure 67: What do the Sevier Orogeny and the Alvord crater have to do with what we can now see in the Grand Canyon? Remember the Gravity Map of the farside of the moon? The distinct bull’s-eye appearance of high and low, red and blue, gravity? If cratering did this to the moon, it also did this to the earth. In spite of all the later cratering, we can see that the Grand Canyon (red oval) lays in a broad blue band that extends well beyond the canyon. If it is dark blue, it was filled with a less dense version of the rock. As I have suggested the Alvord crater deposited the Chuar Formation, so that formation in this area is less dense than the alternative. If that formation is less dense, it will be preferentially eroded by the adiabatic conversion forming release valleys in subsequent cratering. What are some of these larger subsequent craters, and what did they each contribute??? Figure 68: When evaluating what each crater contributed, we have to recognize how the dark blue rings conform to the white rings of that crater. I have already emphasized how the Alvord and Blowout Mountain have a similar foot print and how they both contributed to the Sevier Orogeny. In the Grand Canyon area, the Blowout Mountain produced a couple of additional small up-thrust. I suggest that these up-thrust were smaller because they were working against the low gravity left in the area by the Alvord. The blue ring of the Winnemucca crater extends well beyond both ends of the Grand Canyon’s area. Again the dark blue seems to hug the white rings, strongly indicating that it is a low gravity ring of the Winnemucca crater. The white ring just beyond the canyon did thrust up some mountain ridges, so it would be a compression wave, and the canyon just behind it would be part of the associated release valley. The general line of the canyon appears to mimic the curve of the Winnemucca’s rings.

Figure 68: When evaluating what each crater contributed, we have to recognize how the dark blue rings conform to the white rings of that crater. I have already emphasized how the Alvord and Blowout Mountain have a similar foot print and how they both contributed to the Sevier Orogeny. In the Grand Canyon area, the Blowout Mountain produced a couple of additional small up-thrust. I suggest that these up-thrust were smaller because they were working against the low gravity left in the area by the Alvord. The blue ring of the Winnemucca crater extends well beyond both ends of the Grand Canyon’s area. Again the dark blue seems to hug the white rings, strongly indicating that it is a low gravity ring of the Winnemucca crater. The white ring just beyond the canyon did thrust up some mountain ridges, so it would be a compression wave, and the canyon just behind it would be part of the associated release valley. The general line of the canyon appears to mimic the curve of the Winnemucca’s rings. Figure 69: The Chilili and Gandy craters have one very important aspect in common, both of them include the Grand Canyon within their original crater rim. We saw on the moon’s highlands, the continent of the moon, all of the craters, except the mascons in the largest, have blue centers. The fallback into the crater leaves a less dense lithology. On the Chilili crater the third ring displaced the mountain ridge down Baja California. A larger view would show that slight arc certainly originally aligned with California’s Sierra Nevada, further to the east. The original crater ring on the Gandy crater is outside the edges of the image.

Figure 69: The Chilili and Gandy craters have one very important aspect in common, both of them include the Grand Canyon within their original crater rim. We saw on the moon’s highlands, the continent of the moon, all of the craters, except the mascons in the largest, have blue centers. The fallback into the crater leaves a less dense lithology. On the Chilili crater the third ring displaced the mountain ridge down Baja California. A larger view would show that slight arc certainly originally aligned with California’s Sierra Nevada, further to the east. The original crater ring on the Gandy crater is outside the edges of the image. Figure 70: While the Grand crater included the Grand Canyon within its original crater rings, both the Grand and Navajo craters also contributed to the release valley the Colorado River flows through in the Canyon. With the Grand crater the white arrows point to sections of the river channel that follows the rings. The Yellow arrows indicate other locations that it contributed to the gravity pattern, but the river does not follow it. The river channel southwest of both Kaibab Plateau (K) and Shivwits Plateau (S) are release valleys from Grand crater, while the raised plateaus themselves were produced by the Navajo crater. The inner ring of the Navajo crater is especially easy to see (red arrow) as it is a ridge of high gravity making almost a half-circle. Walhalla Plateau on the southeast pointed end of Kaibab Plateau. It is a nearly isolated plateau surrounded by steep slopes to the Colorado River. I propose it remained a plateau because it was harder, denser because of the added energy put into it by the Navajo crater. Its added density may not reflect different mineral content, but only denser, more tightly packed particle matrix.

Figure 70: While the Grand crater included the Grand Canyon within its original crater rings, both the Grand and Navajo craters also contributed to the release valley the Colorado River flows through in the Canyon. With the Grand crater the white arrows point to sections of the river channel that follows the rings. The Yellow arrows indicate other locations that it contributed to the gravity pattern, but the river does not follow it. The river channel southwest of both Kaibab Plateau (K) and Shivwits Plateau (S) are release valleys from Grand crater, while the raised plateaus themselves were produced by the Navajo crater. The inner ring of the Navajo crater is especially easy to see (red arrow) as it is a ridge of high gravity making almost a half-circle. Walhalla Plateau on the southeast pointed end of Kaibab Plateau. It is a nearly isolated plateau surrounded by steep slopes to the Colorado River. I propose it remained a plateau because it was harder, denser because of the added energy put into it by the Navajo crater. Its added density may not reflect different mineral content, but only denser, more tightly packed particle matrix. Figure 71: The Alaskan crater produced a CGRS just southeast of the white arc that highlights the release-wave response on its backside, The CGRS is accentuated by a second arced linear to the northwest. The red line indicates the shock/compression ridge and the dark blue linear behind it was produced by the following release/expansion wave. The Aguj de Anahuac crater being a smaller crater than the Alaskan, I assume arrived a couple days later. It left a CGRS in a very similar location, but I think the exact location of its release valley better corresponds to the low gravity area connecting the Kaibab and Shivwits Plateaus. A careful examination will show the low gravity linear that makes this central portion of the canyon also had an expression on both the Kaibab and Shivwits Plateaus forming small valleys in its paths across them. This expression on the plateaus is not a feature of the Alaskan craters linear. The Alaskan CGRS probably arrived earlier about the time of the Chuar or Tapeats, while Aguj de Anahuac arrived about the time of the Redwall or Kaibab and left a release valley much higher in the strata.

Figure 71: The Alaskan crater produced a CGRS just southeast of the white arc that highlights the release-wave response on its backside, The CGRS is accentuated by a second arced linear to the northwest. The red line indicates the shock/compression ridge and the dark blue linear behind it was produced by the following release/expansion wave. The Aguj de Anahuac crater being a smaller crater than the Alaskan, I assume arrived a couple days later. It left a CGRS in a very similar location, but I think the exact location of its release valley better corresponds to the low gravity area connecting the Kaibab and Shivwits Plateaus. A careful examination will show the low gravity linear that makes this central portion of the canyon also had an expression on both the Kaibab and Shivwits Plateaus forming small valleys in its paths across them. This expression on the plateaus is not a feature of the Alaskan craters linear. The Alaskan CGRS probably arrived earlier about the time of the Chuar or Tapeats, while Aguj de Anahuac arrived about the time of the Redwall or Kaibab and left a release valley much higher in the strata. Figure 72: Now that we have accounted for some of the sedimentary layers from cratering, how did the canyon form? Could it also be cratering? Some readers will object, but I place the entire canyon as a Release-Valley Canyon formed with the help of the Flagstaff crater. The Flagstaff crater shows up as the blue ring inside the first white ring on gravity. In the Grand Canyon vicinity, the blue ring is diverted to the Canyon which is a dark blue, very low gravity path. That there is little indication of the Flagstaff crater at this resolution on Landsat is not surprising.

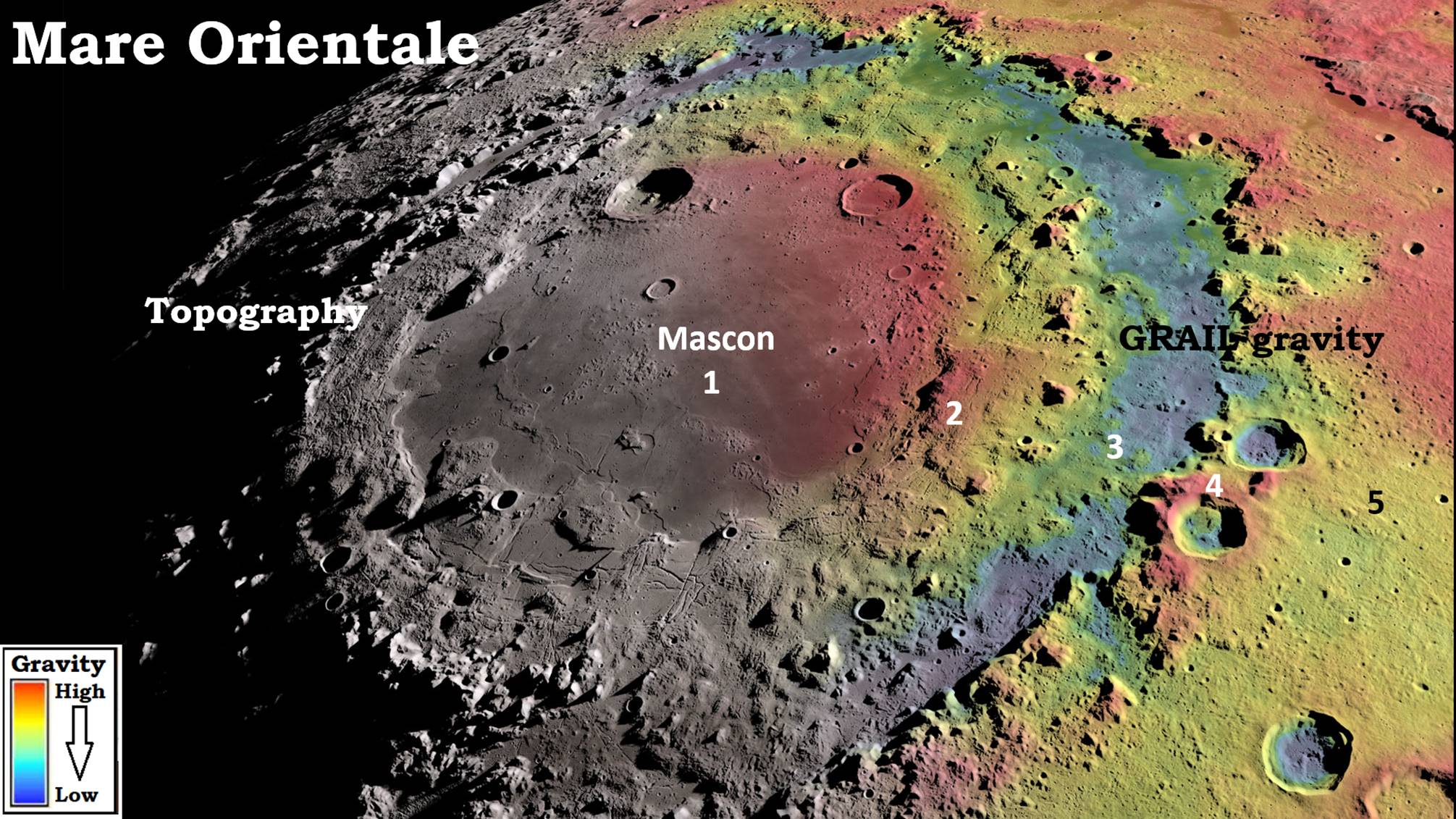

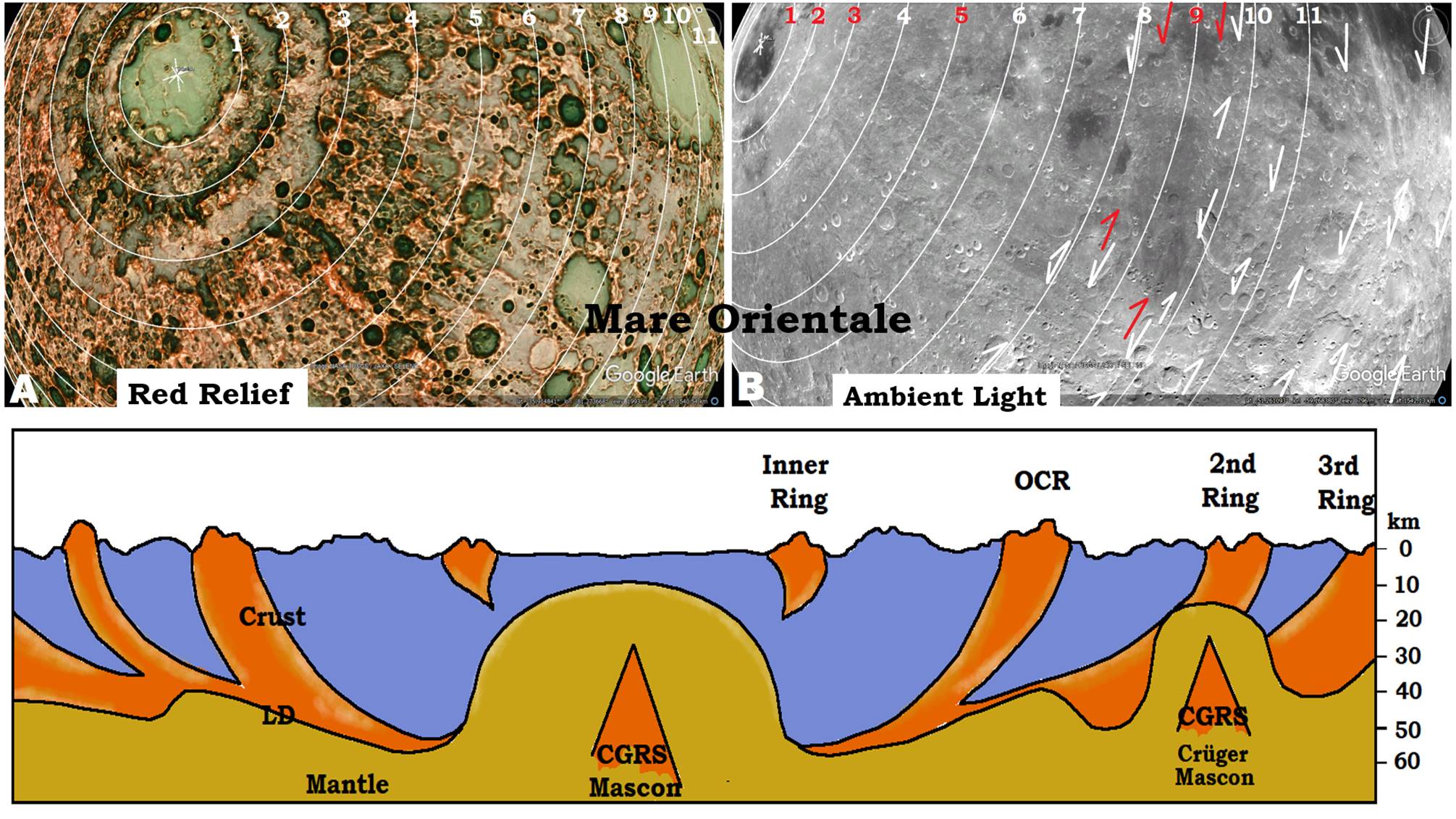

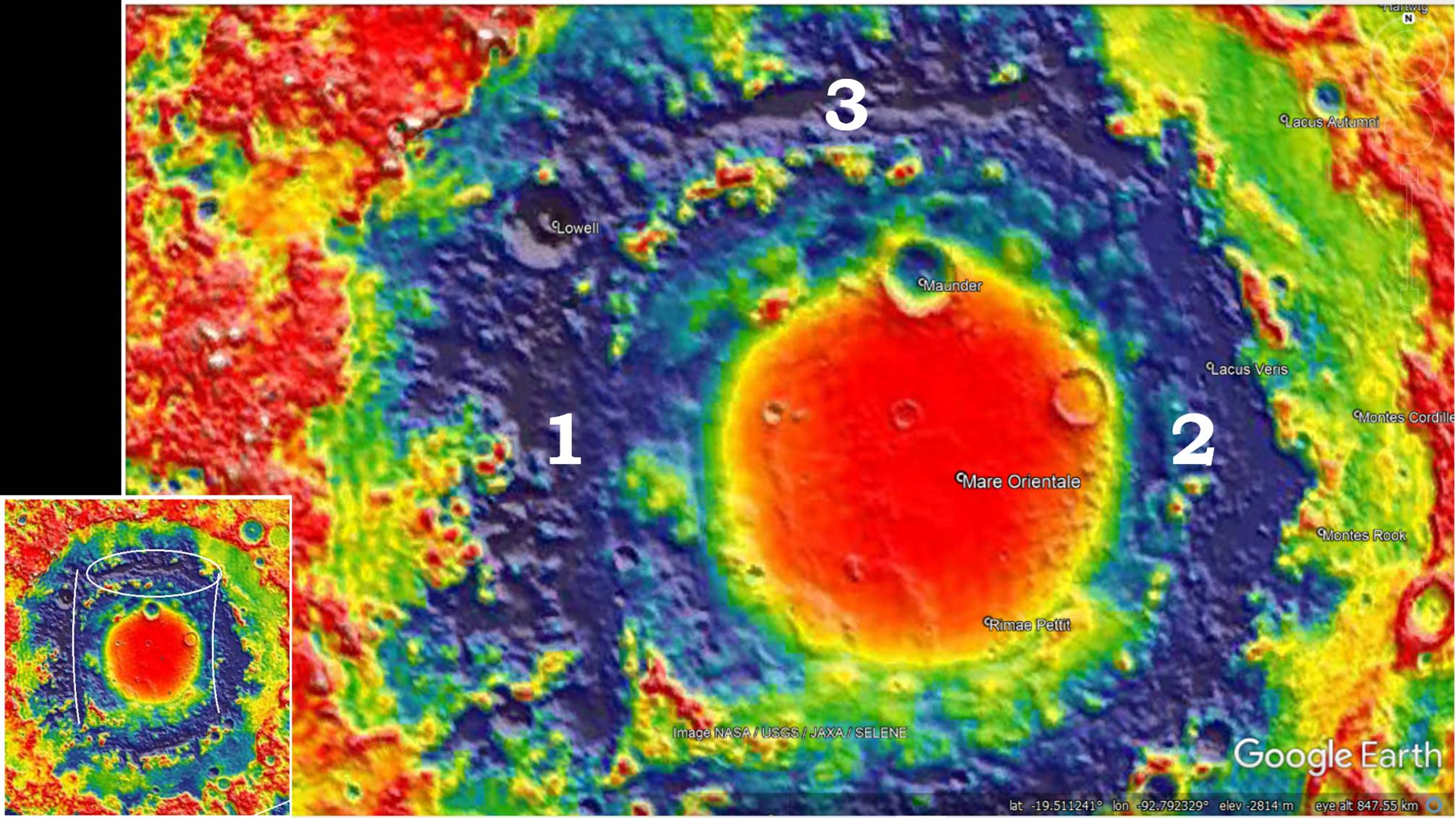

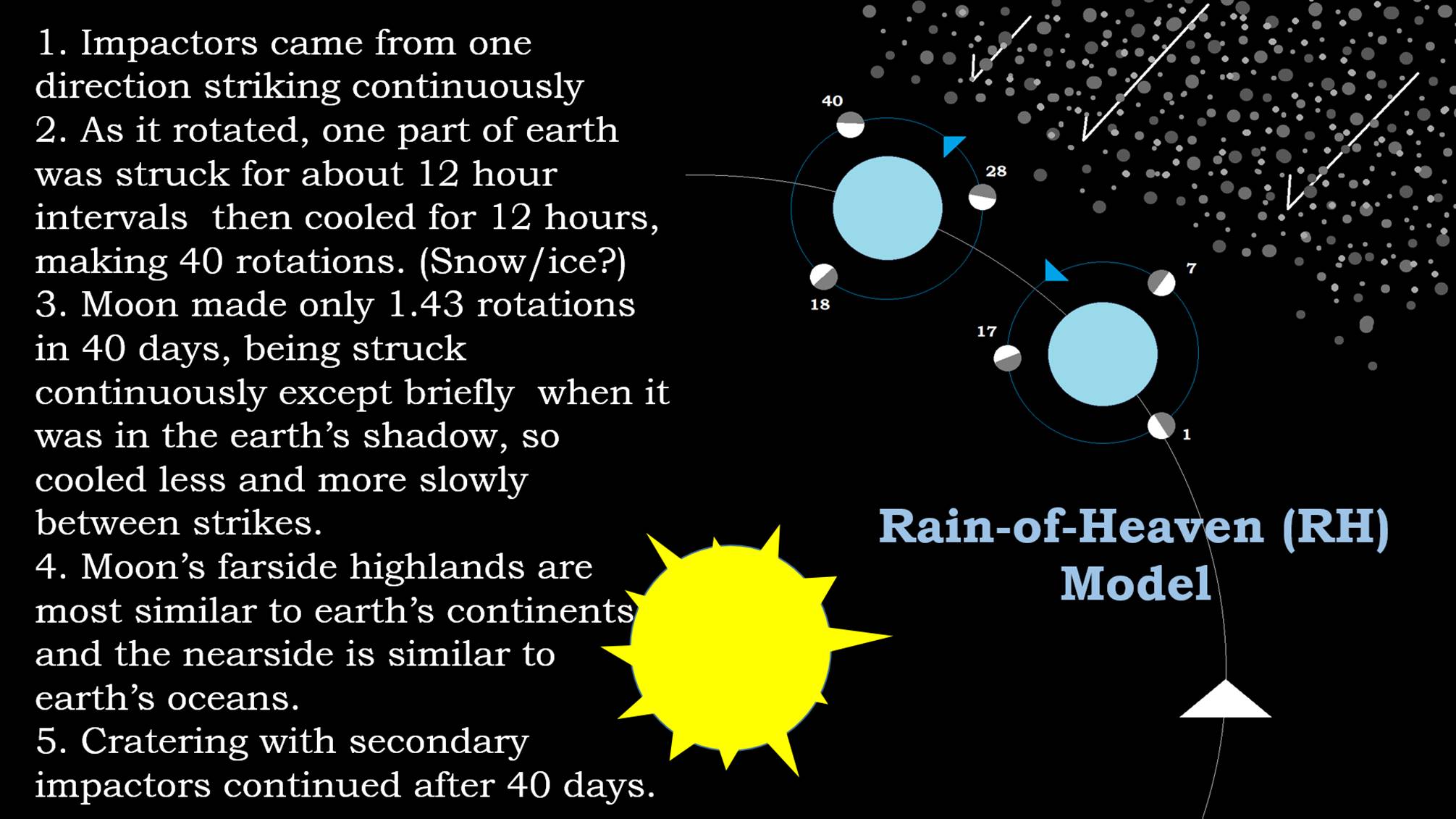

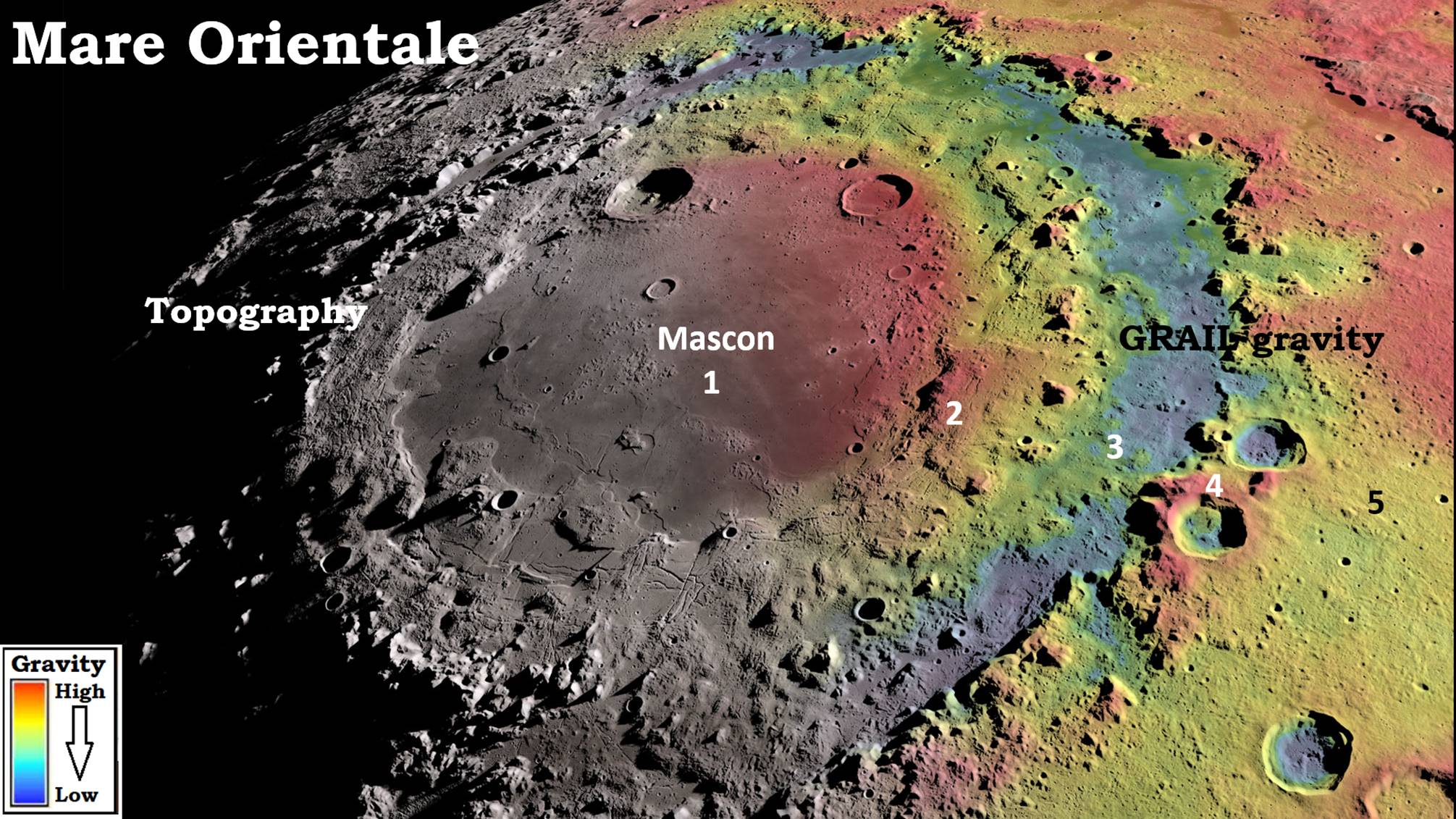

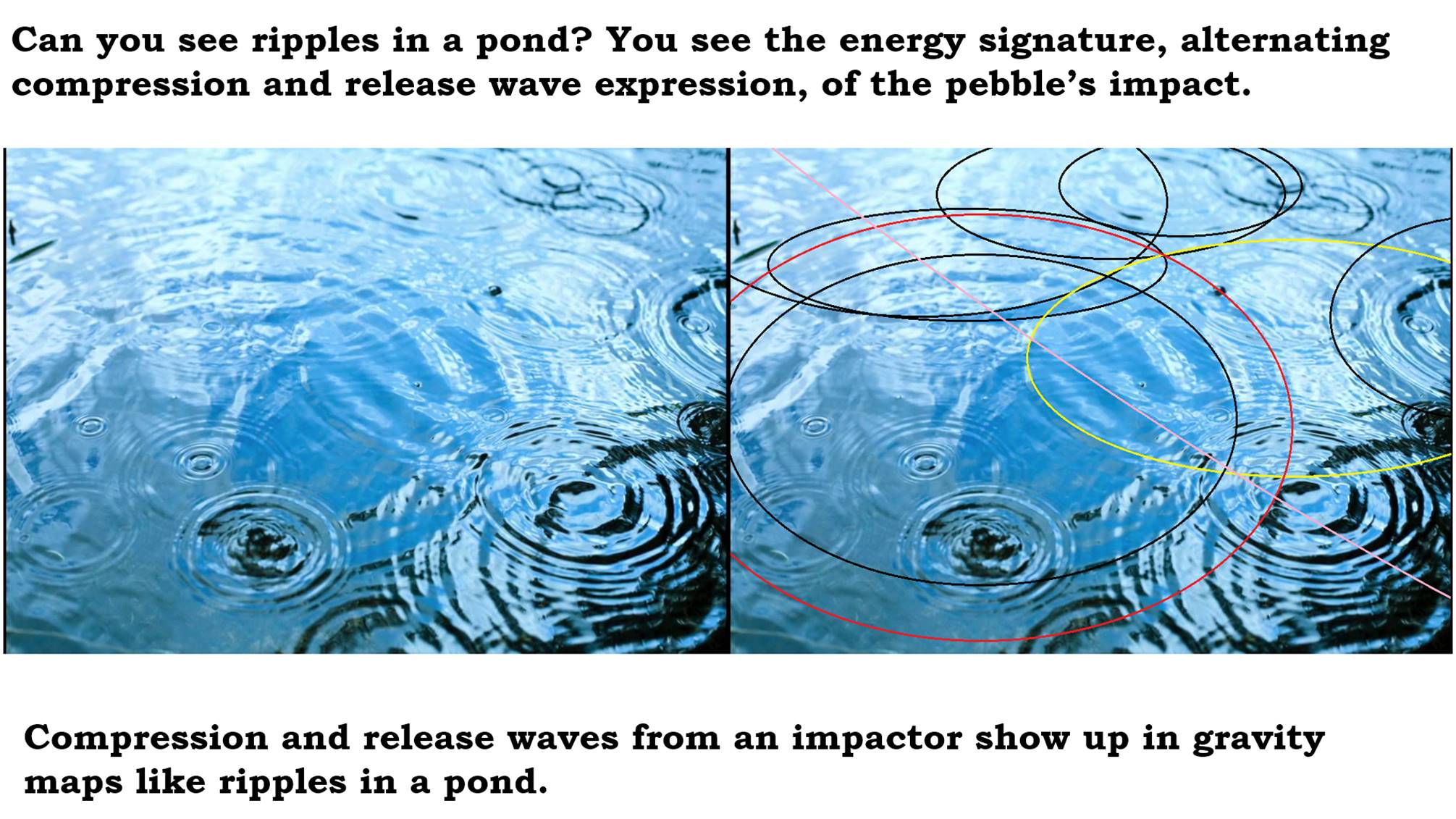

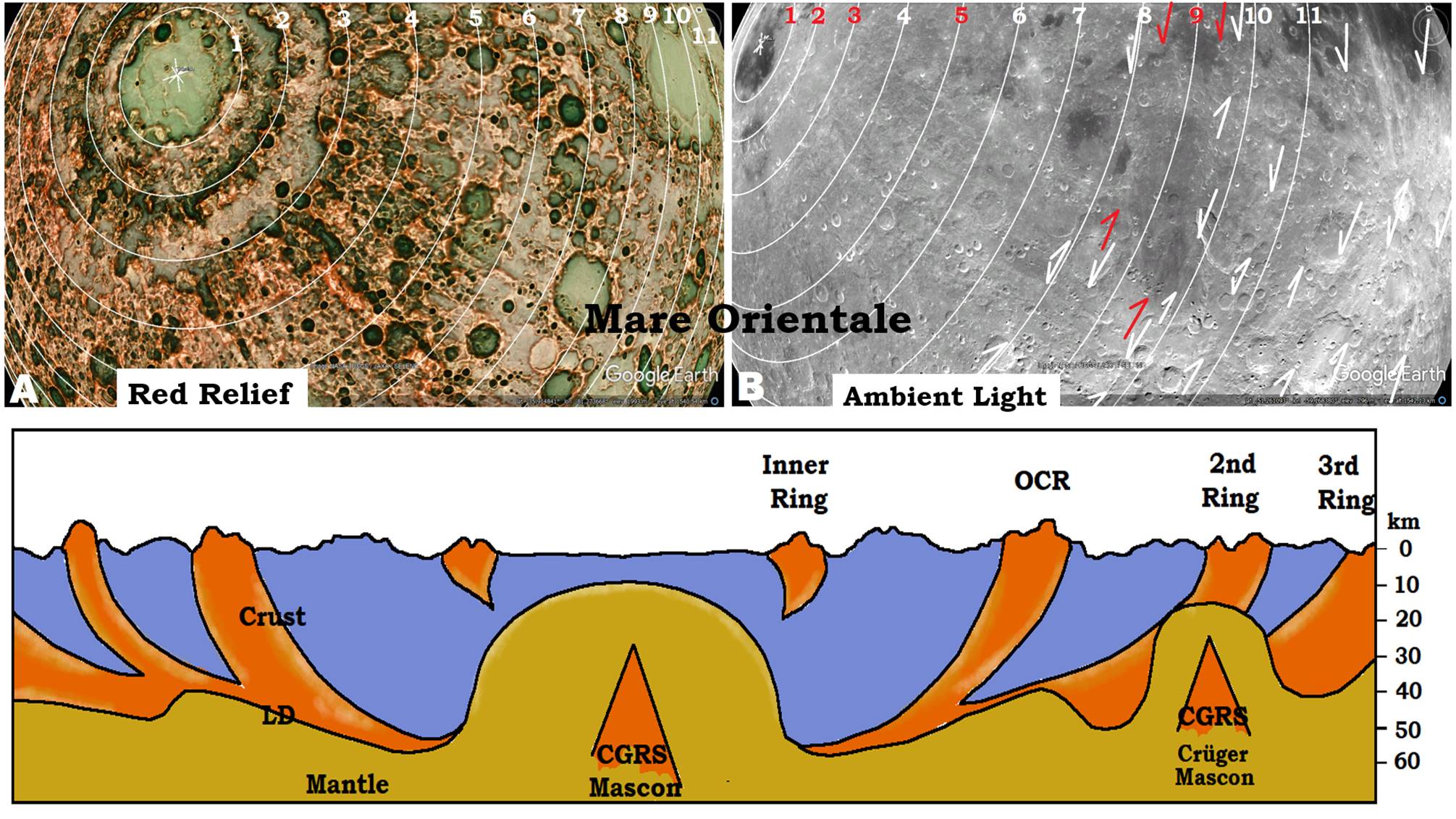

Figure 72: Now that we have accounted for some of the sedimentary layers from cratering, how did the canyon form? Could it also be cratering? Some readers will object, but I place the entire canyon as a Release-Valley Canyon formed with the help of the Flagstaff crater. The Flagstaff crater shows up as the blue ring inside the first white ring on gravity. In the Grand Canyon vicinity, the blue ring is diverted to the Canyon which is a dark blue, very low gravity path. That there is little indication of the Flagstaff crater at this resolution on Landsat is not surprising. Figure 73: Do you see the similarities between the dark blue path of the Grand Canyon and this wiggly canyon I showed you previously in Mare Orientale? The low gravity paths were already formed by the individual adiabatic responses of all of these craters and probably even more. The Flagstaff crater, because of its size I would place late in the 40 days of cratering, maybe between days 35-38. The adiabatic conversion from the Flagstaff crater would have blown much of the sediments out in one puff, and the fast moving water flowing all the way through it would have quickly washed any remaining loose sediments towards the California coast. Some of them may have dropped out of suspension, but I would not look for a “California River” as some papers have proposed. This flow coastward, would have taken place continuously for several days at this time, and would have been rapid but not highly erosive. Note: many of these lines account for the direction of faults within the canyon, and would make an interesting study.

Figure 73: Do you see the similarities between the dark blue path of the Grand Canyon and this wiggly canyon I showed you previously in Mare Orientale? The low gravity paths were already formed by the individual adiabatic responses of all of these craters and probably even more. The Flagstaff crater, because of its size I would place late in the 40 days of cratering, maybe between days 35-38. The adiabatic conversion from the Flagstaff crater would have blown much of the sediments out in one puff, and the fast moving water flowing all the way through it would have quickly washed any remaining loose sediments towards the California coast. Some of them may have dropped out of suspension, but I would not look for a “California River” as some papers have proposed. This flow coastward, would have taken place continuously for several days at this time, and would have been rapid but not highly erosive. Note: many of these lines account for the direction of faults within the canyon, and would make an interesting study. Figure 74: Let us look again at the Flagstaff crater’s rim in topography. The edges of the “crop circle” (“Gulf of Mexico to Turner Gulch” slide show) are marked with the inside end of the yellow lines. I do not believe the “crop circle” would have been recognized if the Flagstaff crater had not been identified first, but it is real. How many other obvious indications of craters occur but are ignored because we are using a different model? One you have seen some of it, it becomes obvious.

Figure 74: Let us look again at the Flagstaff crater’s rim in topography. The edges of the “crop circle” (“Gulf of Mexico to Turner Gulch” slide show) are marked with the inside end of the yellow lines. I do not believe the “crop circle” would have been recognized if the Flagstaff crater had not been identified first, but it is real. How many other obvious indications of craters occur but are ignored because we are using a different model? One you have seen some of it, it becomes obvious. James was writing about the need to practice what we know in our spiritual lives, but it is not an absurd stretch to apply it to everything we know. Is knowing enough? The picture is a poor pun and a tired joke, but you now have new information. Think, what are you going to do with it? Discard it because it can’t possibly be true? Investigate it more? Ignore it because you don’t want it to be true?

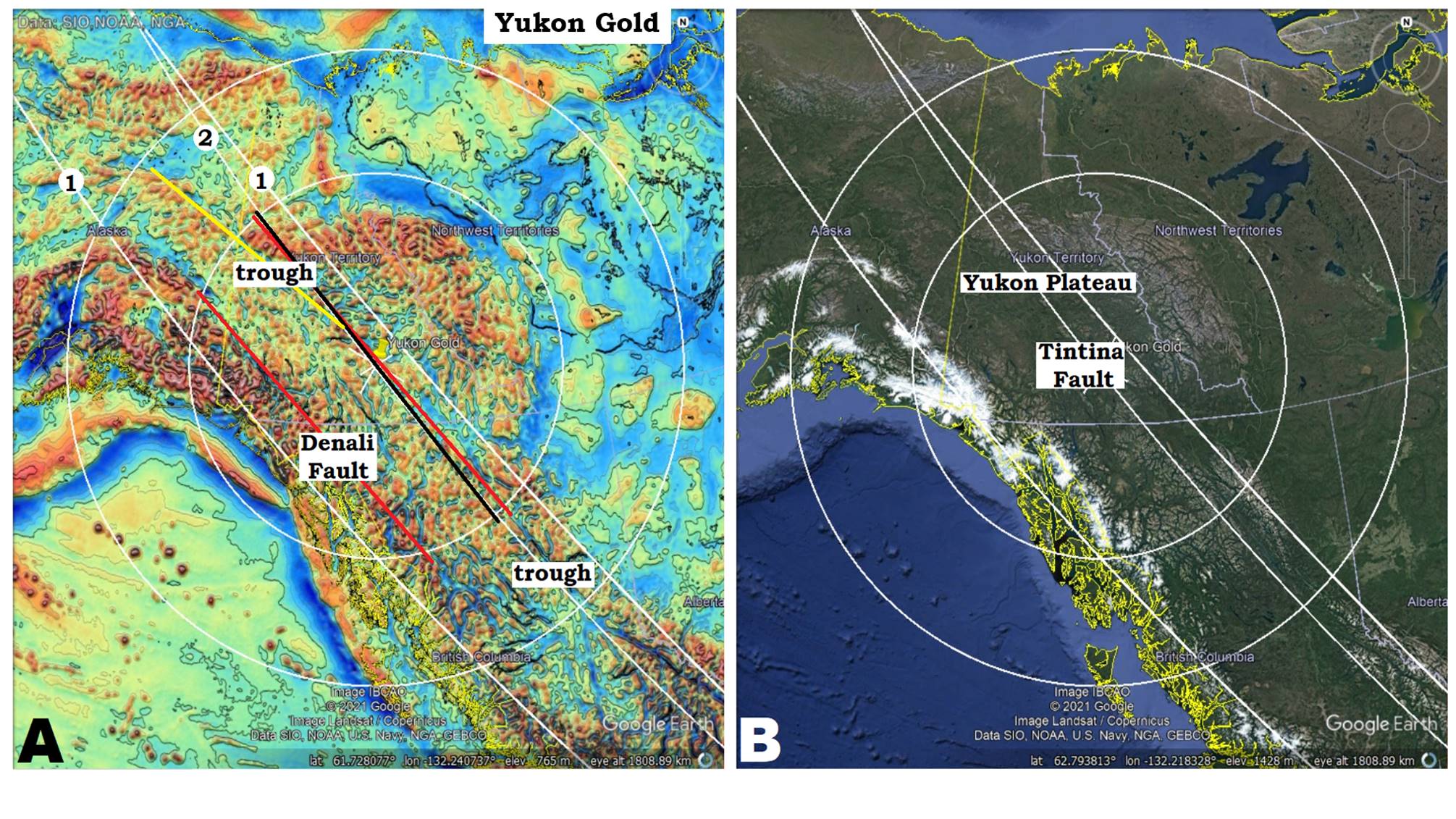

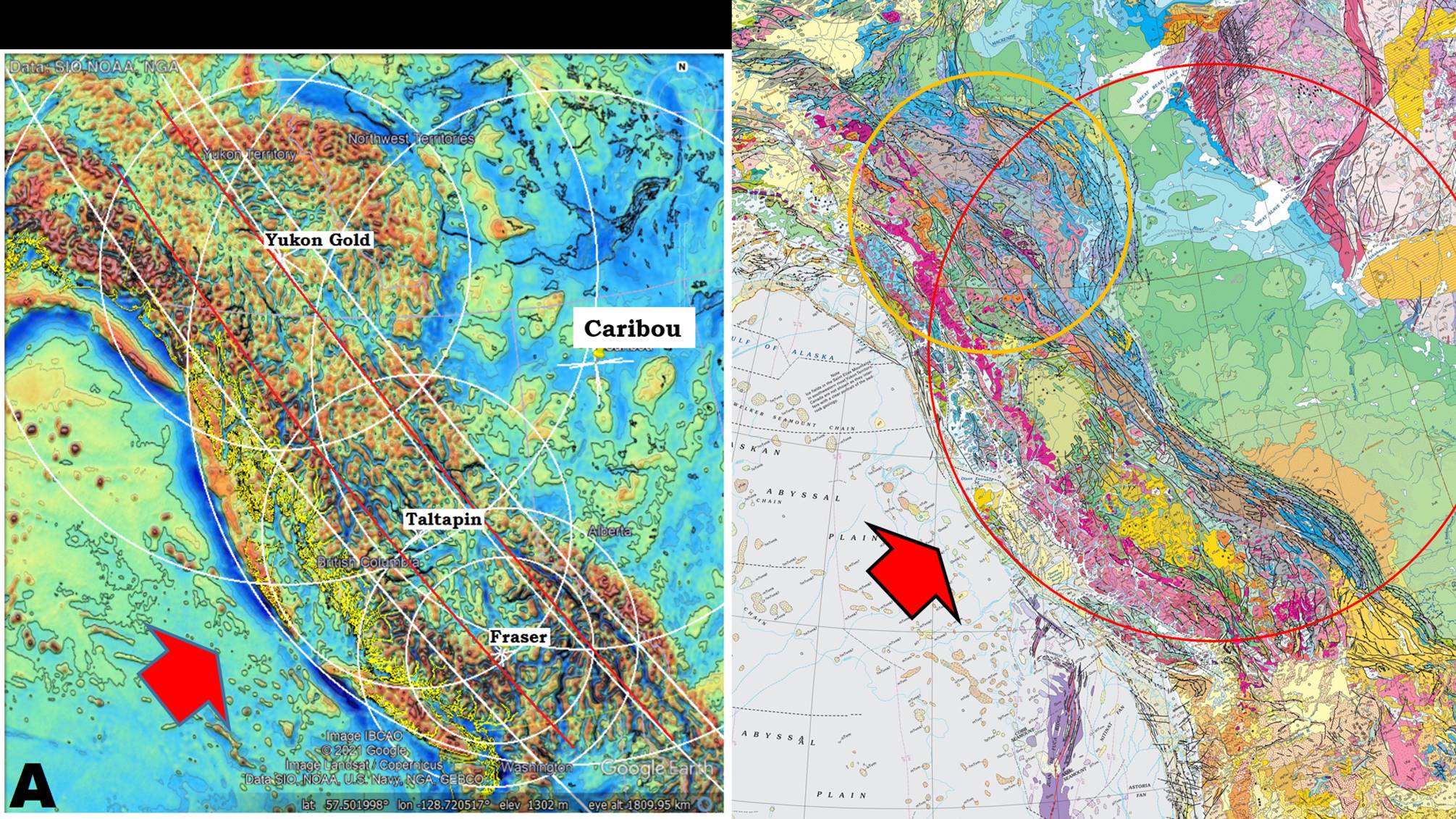

James was writing about the need to practice what we know in our spiritual lives, but it is not an absurd stretch to apply it to everything we know. Is knowing enough? The picture is a poor pun and a tired joke, but you now have new information. Think, what are you going to do with it? Discard it because it can’t possibly be true? Investigate it more? Ignore it because you don’t want it to be true? Figure 75: Can you apply what you have learned to this figure and locate comparable topographic clues in this region for these CGRS. I see clues for each, and clues for many, many more.

Figure 75: Can you apply what you have learned to this figure and locate comparable topographic clues in this region for these CGRS. I see clues for each, and clues for many, many more. Figure 76: One other form of erosion which played a major role in the canyon we see today was small erosion craters that continued throughout the Flood year and into the Post-Flood period. This probably involved secondary impactors which were chunks of lithology that was shot into orbit by the first LARGE impactors. Secondary impactors may have continued till Sodom and Gomorrah. Horseshoe Mesa is a famous landmark with its horseshoe shape and two arms. Can you see the many fracture linears with dark plant growth. How many of them are indicated in the earlier image for cratering fracturing and the Flagstaff crater? At the end of its west arm . . . . . . .

Figure 76: One other form of erosion which played a major role in the canyon we see today was small erosion craters that continued throughout the Flood year and into the Post-Flood period. This probably involved secondary impactors which were chunks of lithology that was shot into orbit by the first LARGE impactors. Secondary impactors may have continued till Sodom and Gomorrah. Horseshoe Mesa is a famous landmark with its horseshoe shape and two arms. Can you see the many fracture linears with dark plant growth. How many of them are indicated in the earlier image for cratering fracturing and the Flagstaff crater? At the end of its west arm . . . . . . . Figure 77: Is a series of circular lineaments in the plateau’s surface. Only the middle of the circles are on the Plateau surface, but I see them very clearly on Google Earth, and they are equally visible on the ground surface. It would be an interesting study to compare limestone in the circles and that more distant. In the second yellow ring, where the purple arrow points on the “thumb” peninsula some very curious minerals are exposed.

Figure 77: Is a series of circular lineaments in the plateau’s surface. Only the middle of the circles are on the Plateau surface, but I see them very clearly on Google Earth, and they are equally visible on the ground surface. It would be an interesting study to compare limestone in the circles and that more distant. In the second yellow ring, where the purple arrow points on the “thumb” peninsula some very curious minerals are exposed. Figure 78: This is the trail out onto the thumb. Around the small tree, along the path and in the distant wall barite is visible. If you ever get down there, the barite is easy to identify. It is white, like cloudy quartz, but four times the density. It feels very heavy. The geologist tell us, barite replaced the quartz chert in these locations. How does chert/quartz melt out of the limestone and make a void barite can fill? It is only about a 6 foot wide band of barite with the quartz chert still present on either side. I suspect either the compression wave or release wave vaporized the quartz in this ring and mobilized the Barite. It would be a great project for some chemistry major’s thesis.

Figure 78: This is the trail out onto the thumb. Around the small tree, along the path and in the distant wall barite is visible. If you ever get down there, the barite is easy to identify. It is white, like cloudy quartz, but four times the density. It feels very heavy. The geologist tell us, barite replaced the quartz chert in these locations. How does chert/quartz melt out of the limestone and make a void barite can fill? It is only about a 6 foot wide band of barite with the quartz chert still present on either side. I suspect either the compression wave or release wave vaporized the quartz in this ring and mobilized the Barite. It would be a great project for some chemistry major’s thesis. Figure 79: This obvious crater is not so obvious from the ground. It is referred to as Phantom Creek Valley, and I believe I have camped in an overhang on the south wall of the crater. I wish I had known about its total shape when I was there. I spent a day climbed all over it. This would be a great location to see specific characteristic of secondary craters. Note the red near the center of the crater. I will assume it is cutting down to the liver red Hakatai Shale. The Hakatai shale is a far reaching red formation, like the Supai and Moenkopi formations. They are red from distinct red crystals of hematite scattered among the white sand and gray shale particles. Distinct hematite crystals require ~1,000 degrees C (1,832 degrees F) to form in the air. They cannot grow between the sand grains. That is why I propose a vapor condensate to form the sediments in the air, not erosional degradation.

Figure 79: This obvious crater is not so obvious from the ground. It is referred to as Phantom Creek Valley, and I believe I have camped in an overhang on the south wall of the crater. I wish I had known about its total shape when I was there. I spent a day climbed all over it. This would be a great location to see specific characteristic of secondary craters. Note the red near the center of the crater. I will assume it is cutting down to the liver red Hakatai Shale. The Hakatai shale is a far reaching red formation, like the Supai and Moenkopi formations. They are red from distinct red crystals of hematite scattered among the white sand and gray shale particles. Distinct hematite crystals require ~1,000 degrees C (1,832 degrees F) to form in the air. They cannot grow between the sand grains. That is why I propose a vapor condensate to form the sediments in the air, not erosional degradation. Figure 80: Looking at the area surrounding that circle in Phantom Creek, I see it as only one of many circles. Should I be misunderstood, I am saying much/most of the topography is shaped into circles produced by secondary impacts that makeup the majority of erosional craters. They continued landing after the 40 days, until the days of Sodom and Gomorrah. This would produce the soil for the earth, but could also produce major post Flood catastrophes.

Figure 80: Looking at the area surrounding that circle in Phantom Creek, I see it as only one of many circles. Should I be misunderstood, I am saying much/most of the topography is shaped into circles produced by secondary impacts that makeup the majority of erosional craters. They continued landing after the 40 days, until the days of Sodom and Gomorrah. This would produce the soil for the earth, but could also produce major post Flood catastrophes. Figure 81: One more look at Hematite. This is the south edge of the Tonto Platform with Cheops Pyramid and Utah Flats in the background. Something turned the normally white Tapeats Sandstone alternating layers of red and white, in a circular shape. Is it the small center of a secondary erosional crater? I believe so.

Figure 81: One more look at Hematite. This is the south edge of the Tonto Platform with Cheops Pyramid and Utah Flats in the background. Something turned the normally white Tapeats Sandstone alternating layers of red and white, in a circular shape. Is it the small center of a secondary erosional crater? I believe so. Figure 82: Many of the side canyons to the Colorado River are still banked with large deposits of “river rounded” cobbles. I would suggest from the image that many are rounded not from tumbling but ablation and show good indication of a heat rind from going through and being spit-out from the adiabatic conversion. I would suggest this happened in the formation of a release valley. The release valley we now call the Grand Canyon.

Figure 82: Many of the side canyons to the Colorado River are still banked with large deposits of “river rounded” cobbles. I would suggest from the image that many are rounded not from tumbling but ablation and show good indication of a heat rind from going through and being spit-out from the adiabatic conversion. I would suggest this happened in the formation of a release valley. The release valley we now call the Grand Canyon. Figure 83: In a rare glimpse inside a heavenly court room where “gods” set in condemnation before God as He recites their failing, Psalm 82 says, because of their actions “all the foundations of the earth are shaken.” Not covered with water, or filled with fire and smoke, although we have seen that is true in other places, but the very foundations of the earth/ continental shelves are shaken. If we are not going to believe this is pure hyperbole or metaphor, it would take quite a large force. That force would be consistent with impacts of the size I am suggesting. Psalms 29 qualifies as a scene out of such a courtroom: The Psalm is not addressed to the Lord, but about the Lord. It is addressed to the “heavenly beings”/ mighty-son. Assuming, Jehovah includes the portion of the Godhead called the “Son/ Jesus,” we must assume an angel (“sons of God”) is being addressed. Because he is mentioned as a “mighty” son, I will suggest a specific angel, Lucifer, because he is commander of other angels. He is being instructed to give Jehovah glory and strength, which Lucifer refused to do when he said, “I will be like the most High (Isaiah 14:14).” Preferring KJV in verse 7, the voice of Jehovah “divideth the flames of fire.” “Flame” not only denotes the burning, but also refers to the “head’ of a spear, the piercing part. Blazing spears are acting upon, piercing, the many waters, and we can reason from their still burning that the waters did not quench them. “Divide” is the same word for the priest dividing the sacrifice, each portion for its specific use. Not that we want to appeal unnecessarily to a miracle, but the “flames of fire” did not land where they wanted, but where the voice of the Lord directed them “over many waters.” Jehovah makes the whole Earth shake and skip, pierced with flames of fire. That is the Flood as Noah and David knew it.

Figure 83: In a rare glimpse inside a heavenly court room where “gods” set in condemnation before God as He recites their failing, Psalm 82 says, because of their actions “all the foundations of the earth are shaken.” Not covered with water, or filled with fire and smoke, although we have seen that is true in other places, but the very foundations of the earth/ continental shelves are shaken. If we are not going to believe this is pure hyperbole or metaphor, it would take quite a large force. That force would be consistent with impacts of the size I am suggesting. Psalms 29 qualifies as a scene out of such a courtroom: The Psalm is not addressed to the Lord, but about the Lord. It is addressed to the “heavenly beings”/ mighty-son. Assuming, Jehovah includes the portion of the Godhead called the “Son/ Jesus,” we must assume an angel (“sons of God”) is being addressed. Because he is mentioned as a “mighty” son, I will suggest a specific angel, Lucifer, because he is commander of other angels. He is being instructed to give Jehovah glory and strength, which Lucifer refused to do when he said, “I will be like the most High (Isaiah 14:14).” Preferring KJV in verse 7, the voice of Jehovah “divideth the flames of fire.” “Flame” not only denotes the burning, but also refers to the “head’ of a spear, the piercing part. Blazing spears are acting upon, piercing, the many waters, and we can reason from their still burning that the waters did not quench them. “Divide” is the same word for the priest dividing the sacrifice, each portion for its specific use. Not that we want to appeal unnecessarily to a miracle, but the “flames of fire” did not land where they wanted, but where the voice of the Lord directed them “over many waters.” Jehovah makes the whole Earth shake and skip, pierced with flames of fire. That is the Flood as Noah and David knew it. Figure 84: But, do I presently have an answer for all of the geologic question? No, but I have enough that I think my model is on the right track. The more details I find, the more answers I can supply. Our Lord’s handiwork always shows in the details. “When I consider the heavens, the work of thy finger, the moon and the stars that thou hast ordained . . . . What is man that thou are mindful of him, and the son of man that thou visited him . . . .?”

Figure 84: But, do I presently have an answer for all of the geologic question? No, but I have enough that I think my model is on the right track. The more details I find, the more answers I can supply. Our Lord’s handiwork always shows in the details. “When I consider the heavens, the work of thy finger, the moon and the stars that thou hast ordained . . . . What is man that thou are mindful of him, and the son of man that thou visited him . . . .?” Once again in the words of David, Psalm 29: “The voice of the Lord is over the waters; the God of Glory thunders, over many waters. The voice of the Lord is powerful; the voice of the Lord is full of majesty. The voice of the Lord breaks the cedars; the Lord breaks the cedars of Lebanon. He makes Lebanon to skip like a calf, and Sirion like a young wild ox. The voice of the lord divides the flaming arrows. The voice of the Lord shakes the wilderness; the Lord shakes the wilderness of Kadesh, The voice of the Lord puts the deer into the pain of birth when its not its time, and devastates the forest, so that in Hs temple all cry, “Glory”. The purpose of the Flood, in my opinion, was to destroy the work of angels with man in the Nephilim Affair, and form a world in which man could once again say, “Glory to God.” Glory to God!

Once again in the words of David, Psalm 29: “The voice of the Lord is over the waters; the God of Glory thunders, over many waters. The voice of the Lord is powerful; the voice of the Lord is full of majesty. The voice of the Lord breaks the cedars; the Lord breaks the cedars of Lebanon. He makes Lebanon to skip like a calf, and Sirion like a young wild ox. The voice of the lord divides the flaming arrows. The voice of the Lord shakes the wilderness; the Lord shakes the wilderness of Kadesh, The voice of the Lord puts the deer into the pain of birth when its not its time, and devastates the forest, so that in Hs temple all cry, “Glory”. The purpose of the Flood, in my opinion, was to destroy the work of angels with man in the Nephilim Affair, and form a world in which man could once again say, “Glory to God.” Glory to God!

Uncategorized

Sevier and Grand Canyon, Pt 2

There may be no other plot of ground so often used to illustrate many of the geologic processes espoused in textbooks than the Grand Canyon. Geologist talk about it like they have the processes all figured out. Is it just possible that they have gotten it all wrong? This presentation is going to suggest unimaginable cratering was responsible for everything we see there, from the rocks, the sequence, the faults, and the actual canyon. None of it got there by geological processes we can see happening around us today. We will question if some of the processes even work the way everyone has assumed they would. Gentle reader, do not be afraid to questions the rocks, the processes, even my model, but above all, question the assumptions both you and I have made. Our God is a God of mystery, but He is also a God of Knowledge. And in knowing, He is worthy of our praise. The first part covered how we interpret Earth craters in light of what we know of moon craters, and understanding the evidence of the energy signature left in the gravity patterns. It looked at some of the largest craters found in North America, forming the crystalline basement of the continent.

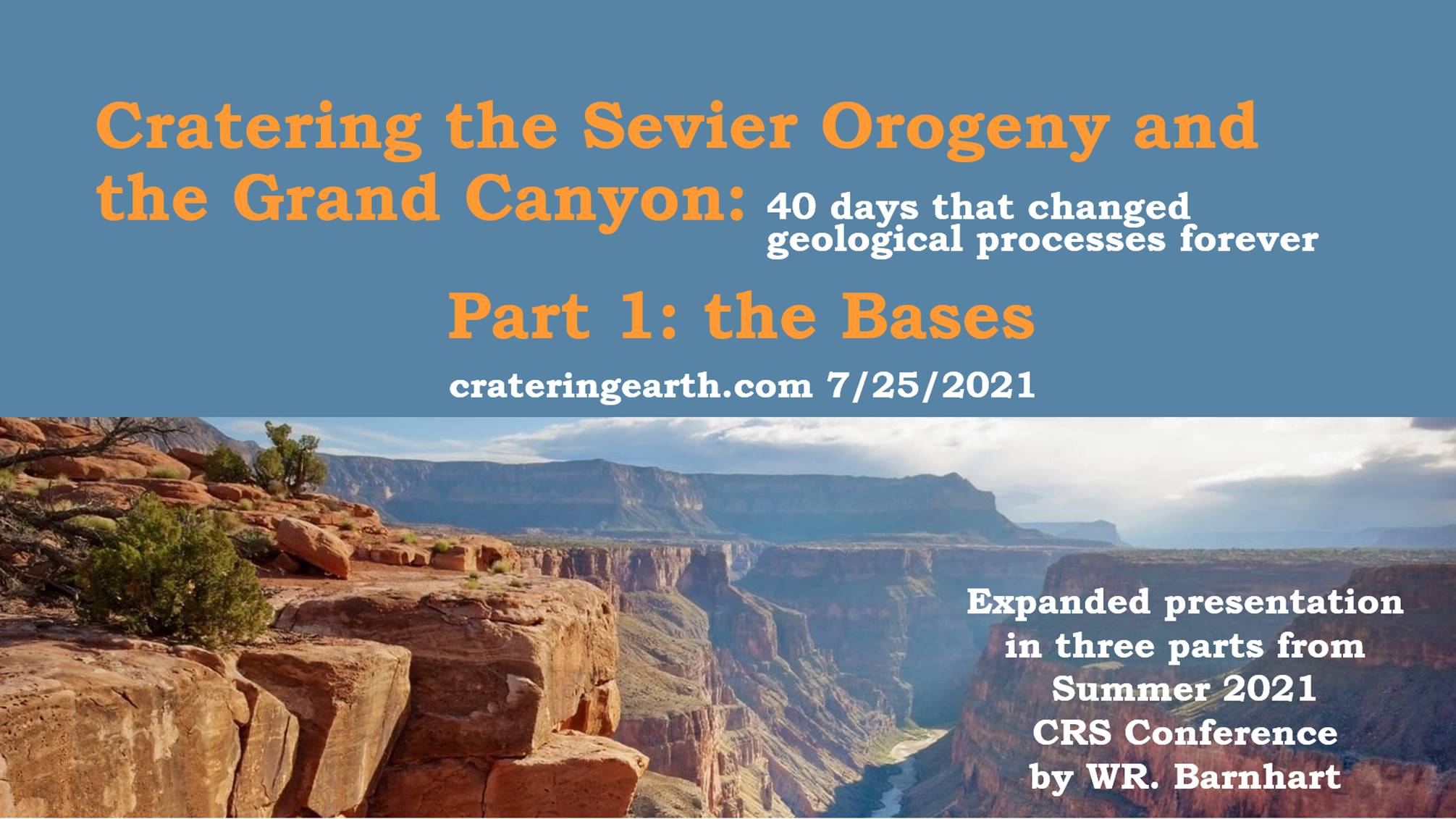

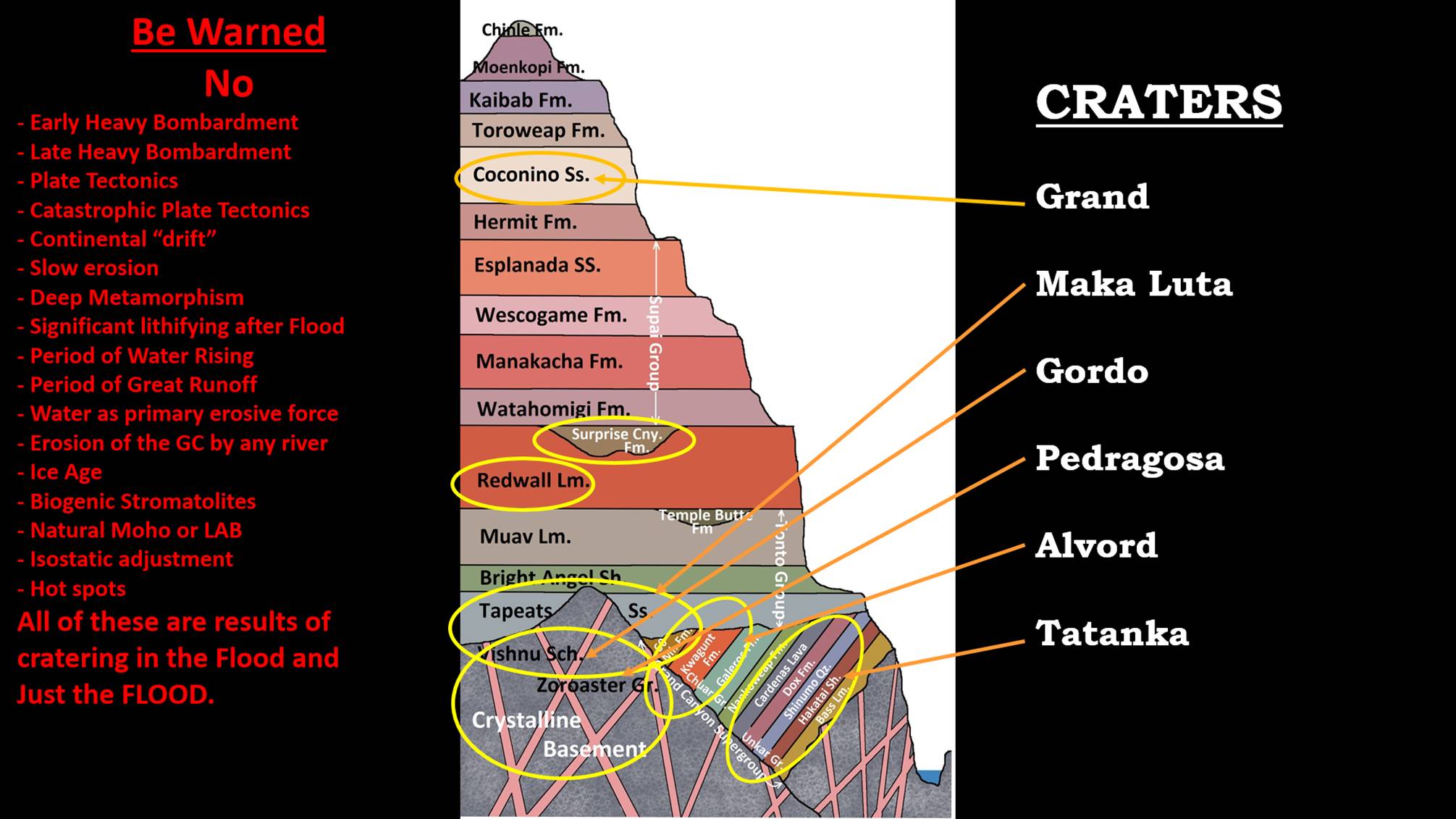

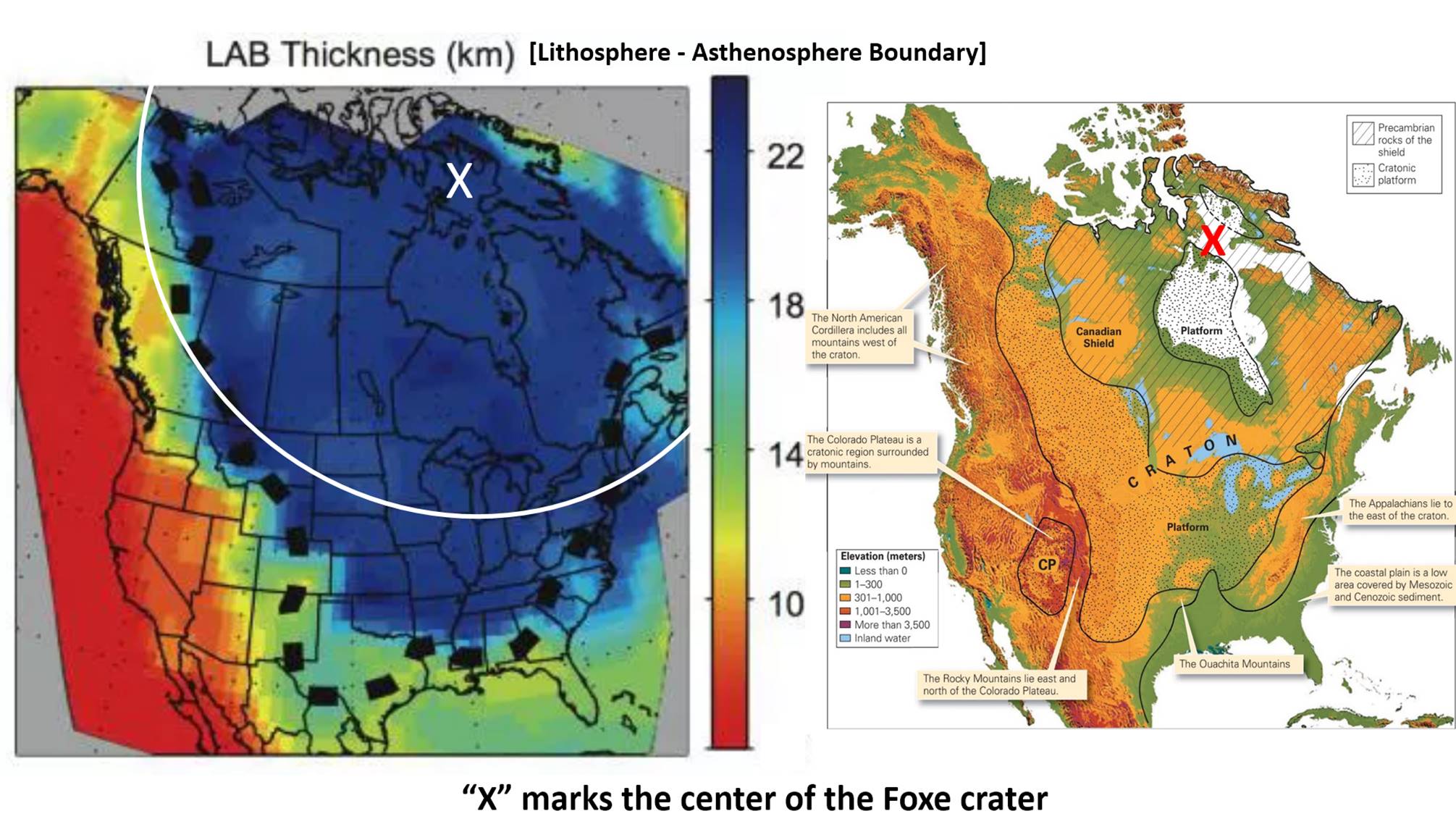

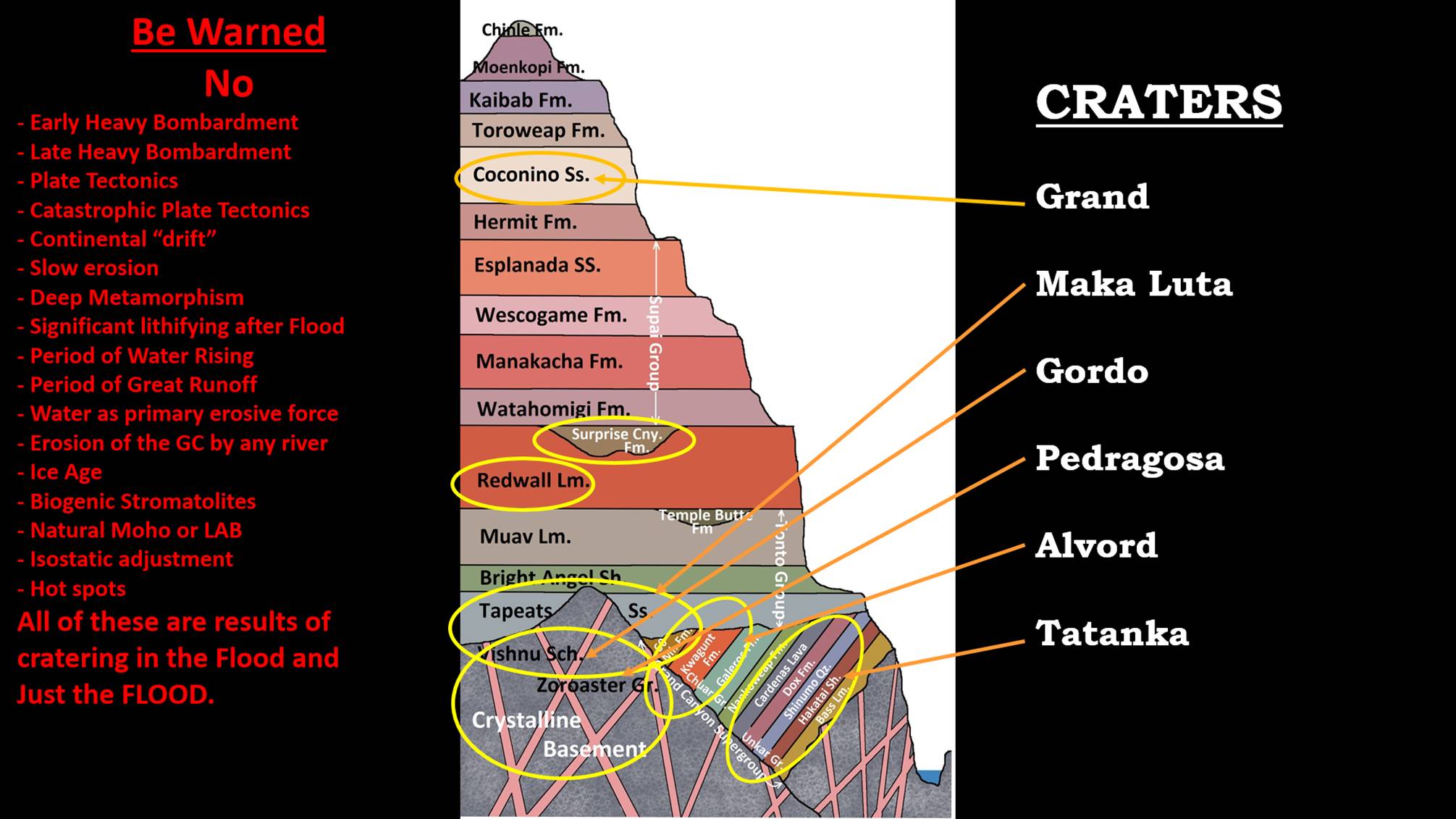

There may be no other plot of ground so often used to illustrate many of the geologic processes espoused in textbooks than the Grand Canyon. Geologist talk about it like they have the processes all figured out. Is it just possible that they have gotten it all wrong? This presentation is going to suggest unimaginable cratering was responsible for everything we see there, from the rocks, the sequence, the faults, and the actual canyon. None of it got there by geological processes we can see happening around us today. We will question if some of the processes even work the way everyone has assumed they would. Gentle reader, do not be afraid to questions the rocks, the processes, even my model, but above all, question the assumptions both you and I have made. Our God is a God of mystery, but He is also a God of Knowledge. And in knowing, He is worthy of our praise. The first part covered how we interpret Earth craters in light of what we know of moon craters, and understanding the evidence of the energy signature left in the gravity patterns. It looked at some of the largest craters found in North America, forming the crystalline basement of the continent. We have covered the cratering below the Great Unconformity the Crystalline Basement in Part 1. Here we want to continue on an exploration trip. Please leave your geologic preconception at the door, and we can go on a trip to discover some new ones. This session will address evidence of astral-cratering covers the entire globe 40 layers deep, We will relate cratering as the cause of the Vishnu Schist, Zoroaster Granite, Unkar Group, the Chuar Group, the 60 Mile and Tapeats Formations, the Redwall, the Surprise Canyon Valleys, and the Coconino Sandstone as well as others. Cratering was responsible for all aspects of the Grand Canyon from the strata to excavating the canyon itself.

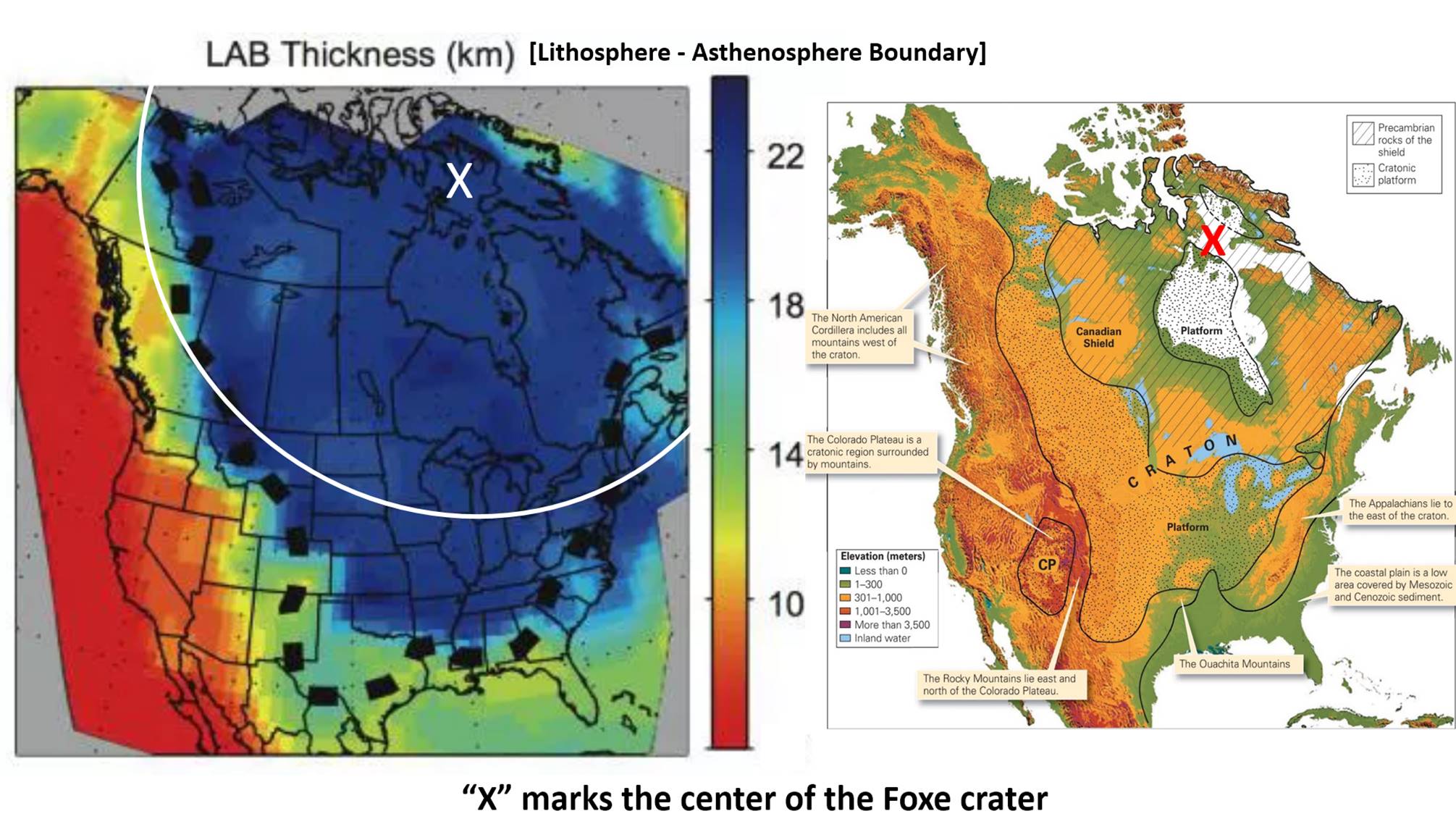

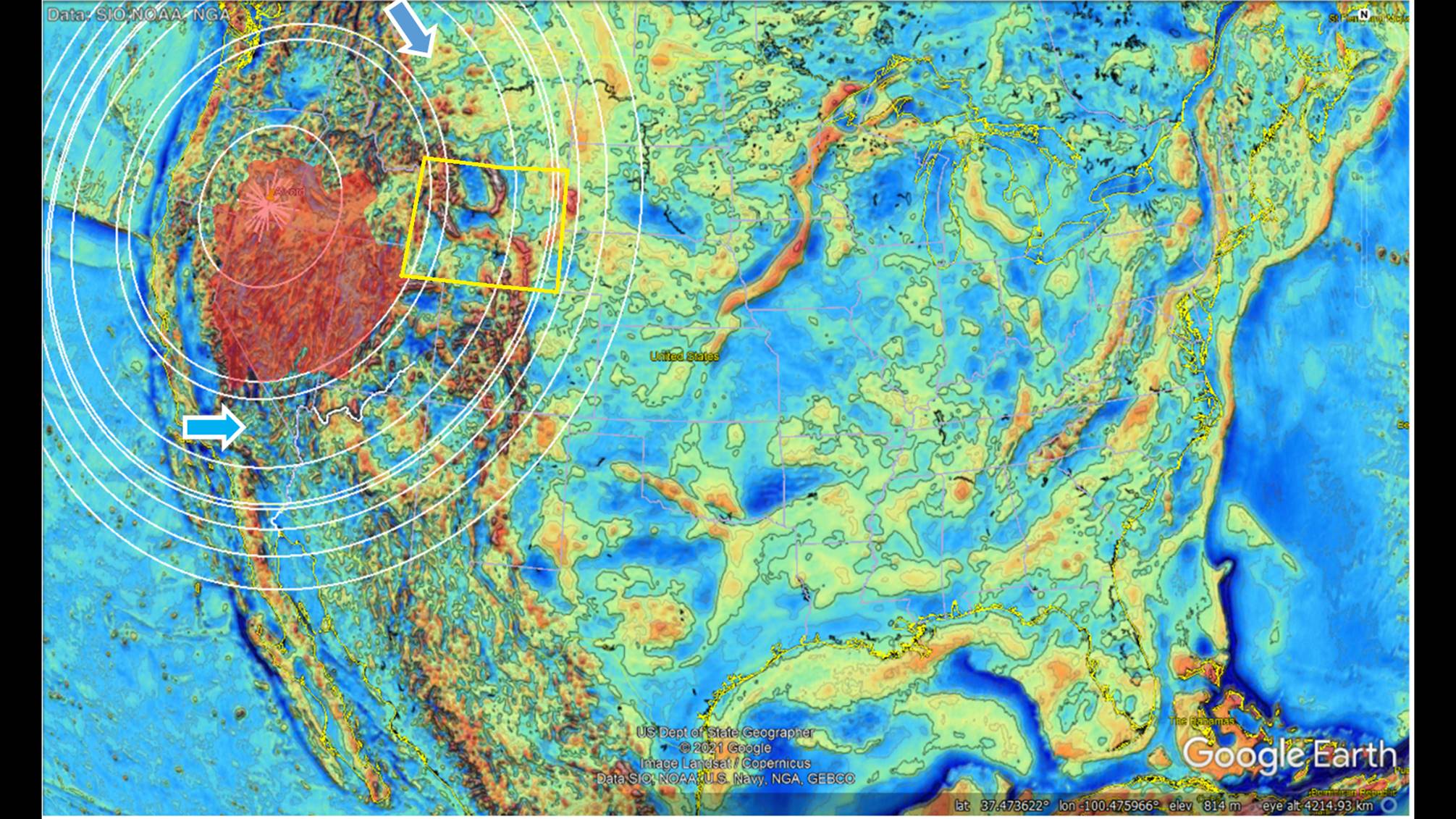

We have covered the cratering below the Great Unconformity the Crystalline Basement in Part 1. Here we want to continue on an exploration trip. Please leave your geologic preconception at the door, and we can go on a trip to discover some new ones. This session will address evidence of astral-cratering covers the entire globe 40 layers deep, We will relate cratering as the cause of the Vishnu Schist, Zoroaster Granite, Unkar Group, the Chuar Group, the 60 Mile and Tapeats Formations, the Redwall, the Surprise Canyon Valleys, and the Coconino Sandstone as well as others. Cratering was responsible for all aspects of the Grand Canyon from the strata to excavating the canyon itself. Figure 32: The Foxe crater, covered in Part 1, in far northern Canada, is the largest crater in North America (that I can find), what is the biggest crater in the continental United States? That distinction goes to the Tatanka crater, whose impactor nearly landed in Canada.

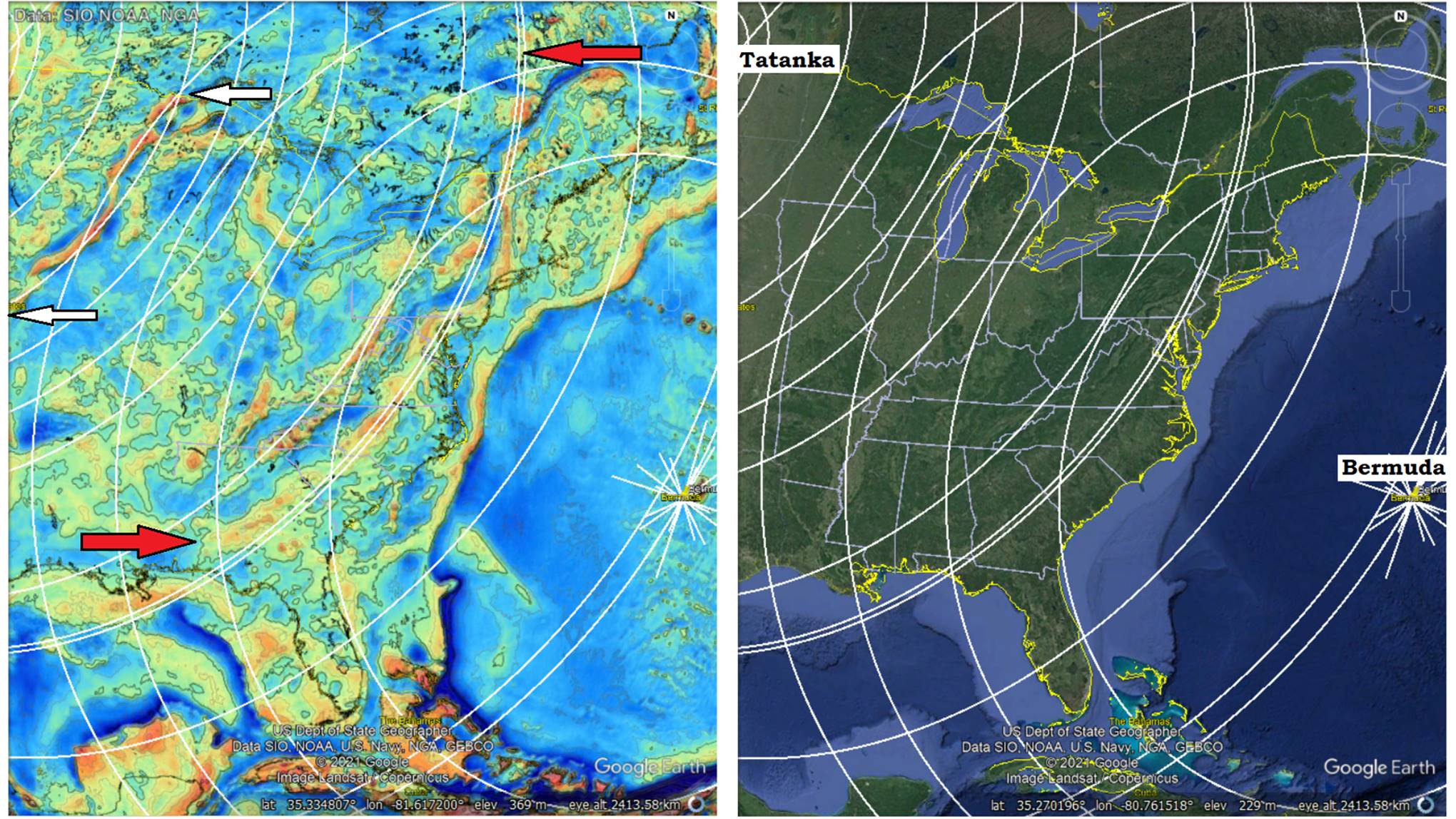

Figure 32: The Foxe crater, covered in Part 1, in far northern Canada, is the largest crater in North America (that I can find), what is the biggest crater in the continental United States? That distinction goes to the Tatanka crater, whose impactor nearly landed in Canada. Figure 33: The Tatanka crater has the Williston Basin at its center. Scanning the gravity map, the Tatanka crater is partially responsible for the red ridge near its 4-ring (between white arrows), the western branch of the Mid Continental Rift, and the 8-9-ring near the east coast (between red arrows) formed the curved ridge of the Appalachian Mountains, as a mascon of the Bermuda crater.

Figure 33: The Tatanka crater has the Williston Basin at its center. Scanning the gravity map, the Tatanka crater is partially responsible for the red ridge near its 4-ring (between white arrows), the western branch of the Mid Continental Rift, and the 8-9-ring near the east coast (between red arrows) formed the curved ridge of the Appalachian Mountains, as a mascon of the Bermuda crater. Figure 34: One way to identify and confirm craters is to recognize how they interact with other craters. The white arrows are still the ends of the west limb of the Mid Continental Rift, and the red arrows are still the ends of the Appalachian ridge. I will propose the Bermuda crater arrived first because it is further to the east, with the Tatanka crater arriving later that same day as the earth rotated under the asteroid shower. The impacts together put extra energy into the area of the Mid Continental Rift where their rings overlap. This increased energy was raised as a mascon by the MCR crater a few days later. In the Appalachians, the arc of the ridge was pushed up in the heated lithosphere from the Bermuda crater. Since the red arrows both occur just outside the second ring, I will identify that as the Open-ring and make that a mascon of the Bermuda crater. The interactions of the two crater’s rims provides conformation for both of them to me, and provides conformation of the model.

Figure 34: One way to identify and confirm craters is to recognize how they interact with other craters. The white arrows are still the ends of the west limb of the Mid Continental Rift, and the red arrows are still the ends of the Appalachian ridge. I will propose the Bermuda crater arrived first because it is further to the east, with the Tatanka crater arriving later that same day as the earth rotated under the asteroid shower. The impacts together put extra energy into the area of the Mid Continental Rift where their rings overlap. This increased energy was raised as a mascon by the MCR crater a few days later. In the Appalachians, the arc of the ridge was pushed up in the heated lithosphere from the Bermuda crater. Since the red arrows both occur just outside the second ring, I will identify that as the Open-ring and make that a mascon of the Bermuda crater. The interactions of the two crater’s rims provides conformation for both of them to me, and provides conformation of the model. Figure 35: The Tatanka crater also has several linears to recognize it, both high and low gravity. The red-ring with the red arrow was the first I thought I saw. Do you ever feel like there is someone staring at you? Some would say this is an unfounded feeling, but other times, with careful examination we can recognize clues that we may not even have previously been aware of. People turned our way. People staring at us. All of these are clues others are listening. Scanning this image may give you a feeling that there are other circular rings concentric to the white rings.

Figure 35: The Tatanka crater also has several linears to recognize it, both high and low gravity. The red-ring with the red arrow was the first I thought I saw. Do you ever feel like there is someone staring at you? Some would say this is an unfounded feeling, but other times, with careful examination we can recognize clues that we may not even have previously been aware of. People turned our way. People staring at us. All of these are clues others are listening. Scanning this image may give you a feeling that there are other circular rings concentric to the white rings. Figure 36: Many will say, with a crater this large, I could not possible really be seeing rings in the gravity pattern. I will say, they are not continuous rings, but they are significant repeated portions of rings. Enough to say, there is something there, and it needs more investigating.

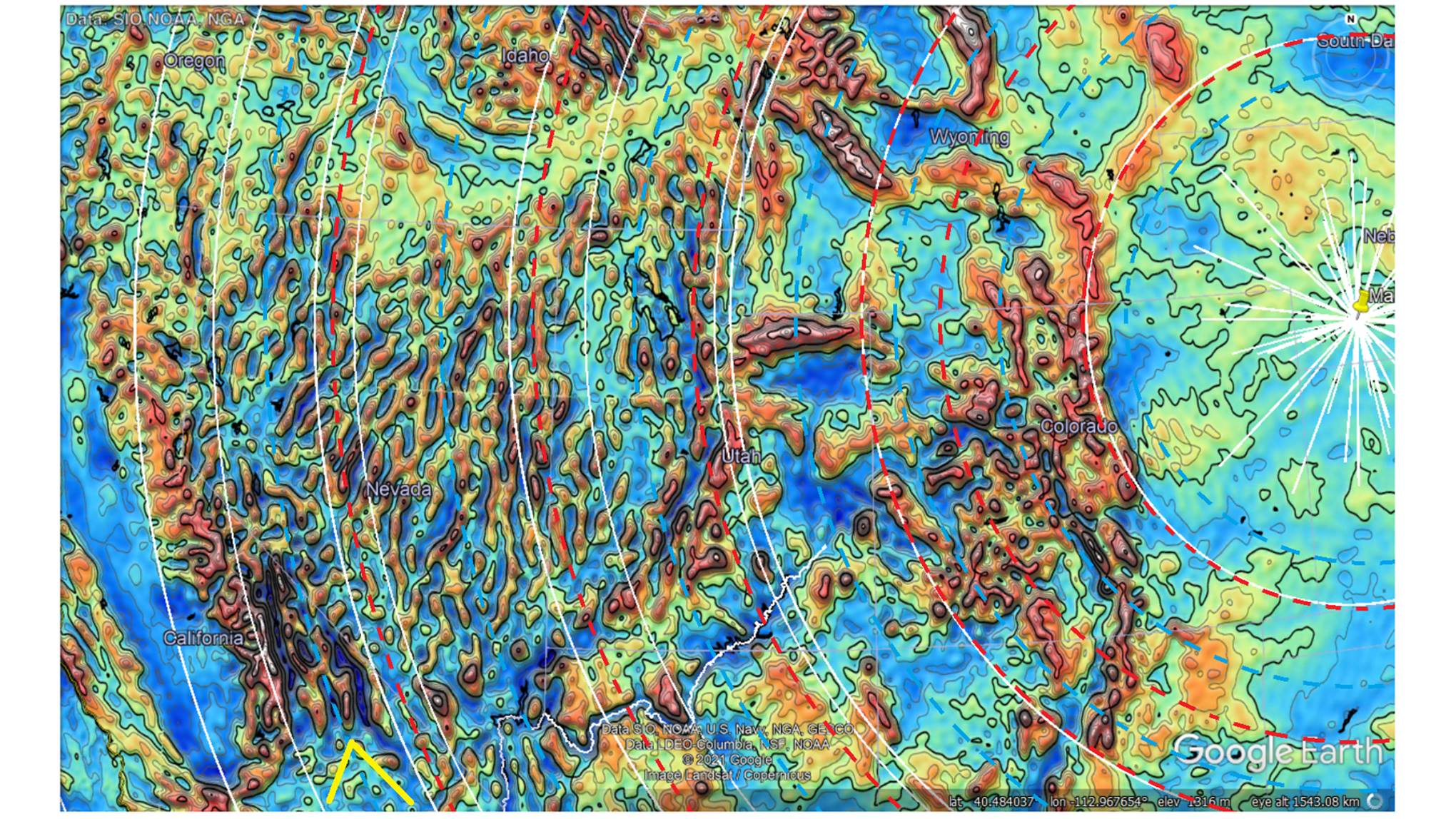

Figure 36: Many will say, with a crater this large, I could not possible really be seeing rings in the gravity pattern. I will say, they are not continuous rings, but they are significant repeated portions of rings. Enough to say, there is something there, and it needs more investigating. Figure 37: South of the Tatanka crater, centered in Nebraska is the Maka Luta crater. “Maka Luta” comes from the Lakota words for “red earth.” A Landsat image of the crater provides very little evidence other than its inside ring fits a curve in the Front Range of Colorado (Red oval).

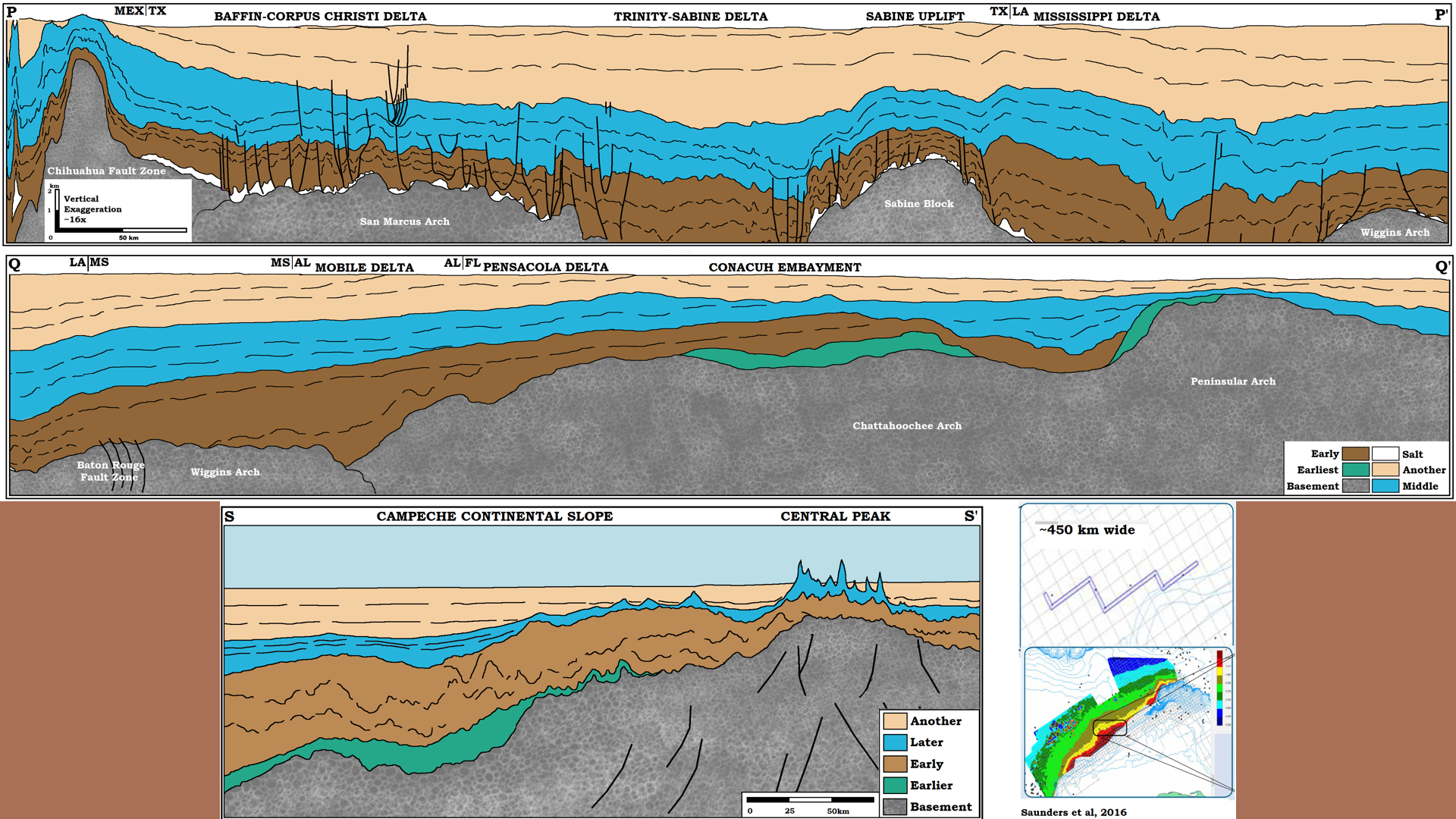

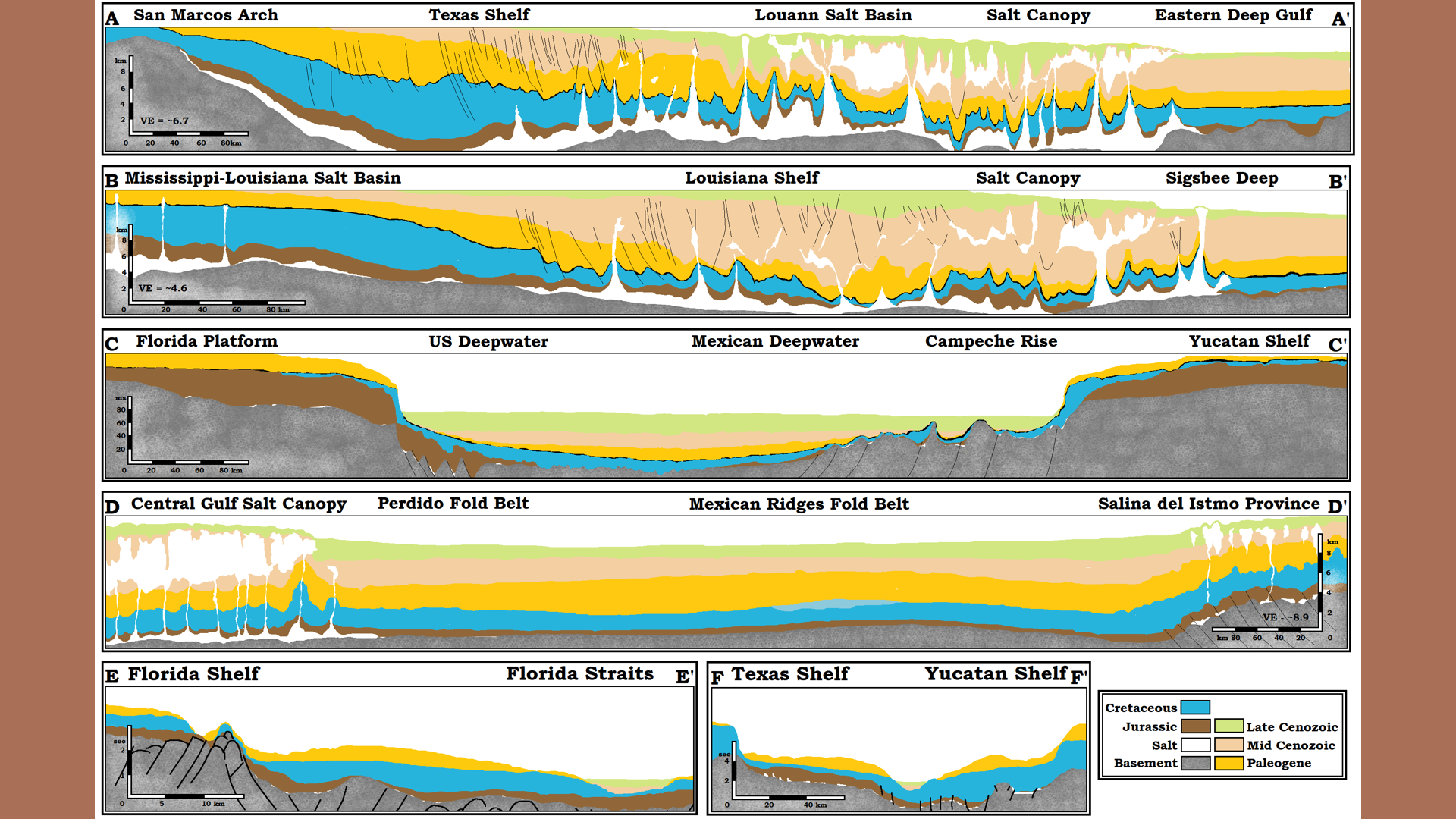

Figure 37: South of the Tatanka crater, centered in Nebraska is the Maka Luta crater. “Maka Luta” comes from the Lakota words for “red earth.” A Landsat image of the crater provides very little evidence other than its inside ring fits a curve in the Front Range of Colorado (Red oval). Figure 38: At the center of the Maka Luta crater is the Denver-Julesburg Basin, and at its outer edge is the edge of the continental shelves. Some creation authors have tried to make the Continental Shelves a product of the sediments running off of the continents as the land supposedly rose. This cannot be true if the Continental Shelves are part of the continents, and seismic sections consistently show them to be such, no matter where we look. On the east coast the high gravity ridge of the Continental Shelf is an up thrust of the Maka Luta, and while this map does not show the west coast to be similarly designed, the topographic sections do (see Pacific Northwest slideshow). In the Gulf of Mexico, the ring also limited the continent, but that limit was shortly modified by the Sigsbee Escarpment which pushed-up through the sediments from the MCR (Mid Continental Rift) crater. The Maka Luta crater determined the foundations of the continent.

Figure 38: At the center of the Maka Luta crater is the Denver-Julesburg Basin, and at its outer edge is the edge of the continental shelves. Some creation authors have tried to make the Continental Shelves a product of the sediments running off of the continents as the land supposedly rose. This cannot be true if the Continental Shelves are part of the continents, and seismic sections consistently show them to be such, no matter where we look. On the east coast the high gravity ridge of the Continental Shelf is an up thrust of the Maka Luta, and while this map does not show the west coast to be similarly designed, the topographic sections do (see Pacific Northwest slideshow). In the Gulf of Mexico, the ring also limited the continent, but that limit was shortly modified by the Sigsbee Escarpment which pushed-up through the sediments from the MCR (Mid Continental Rift) crater. The Maka Luta crater determined the foundations of the continent. Figure 39: Looking at the Maka Luta crater’s pattern as it crosses the Rocky Mountains, it also produced a gravity pattern of ripples. When finding the cratering connection to the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, it quickly becomes evident something cut them off on their south end (yellow arrow). Part of that something was the wide dark-blue ring which includes Owens Valley and Death Valley, both very significant to geologist in California. While both had their ultimate shape determined by other, later craters. The first low gravity print was made by the Maka Luta crater, which included them in a release valley. Looking north from that area, a number of dark-blue areas are concentric to the Maka Luta’s expression all across the Basin and Range and Rocky Mountains.

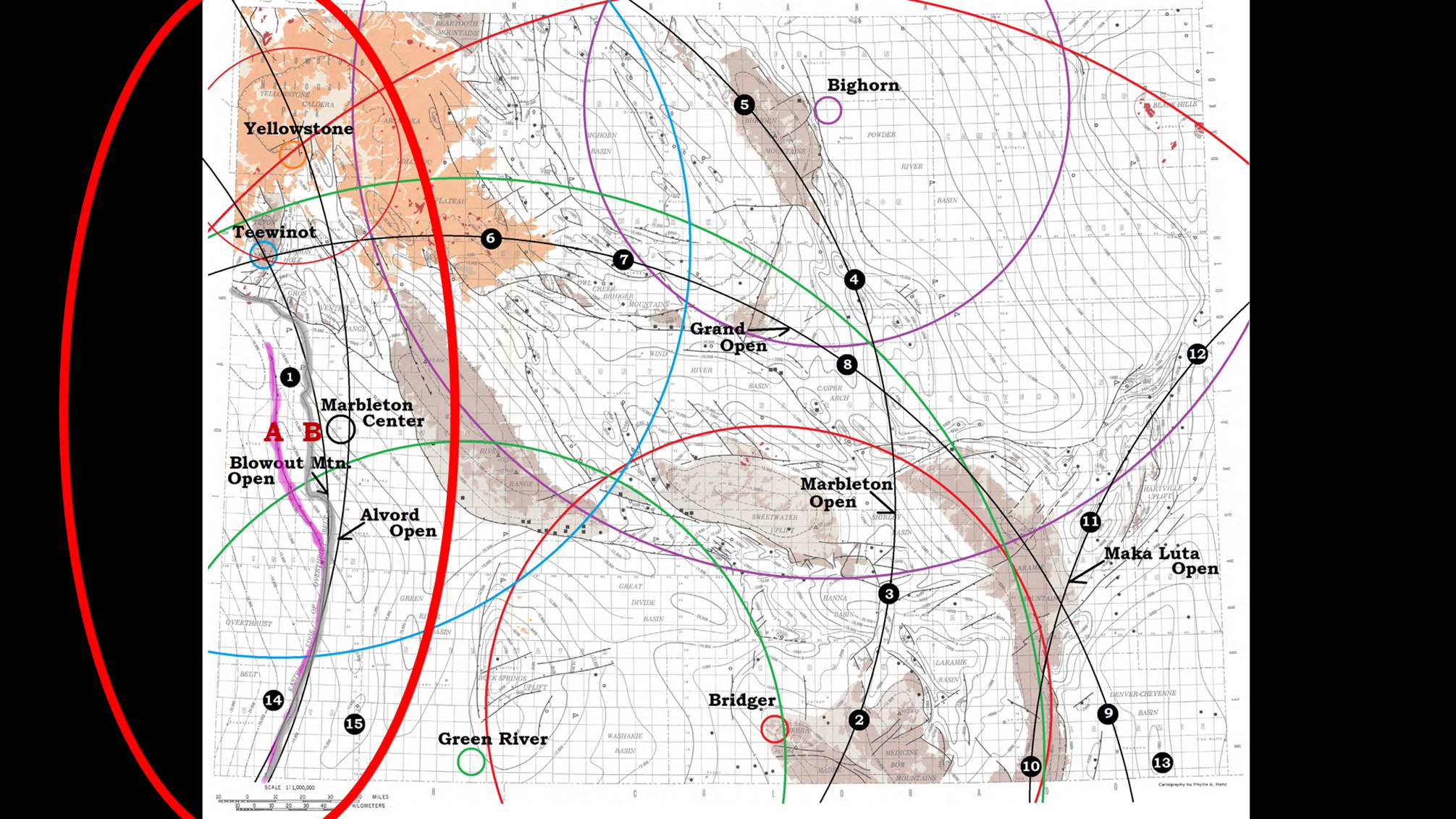

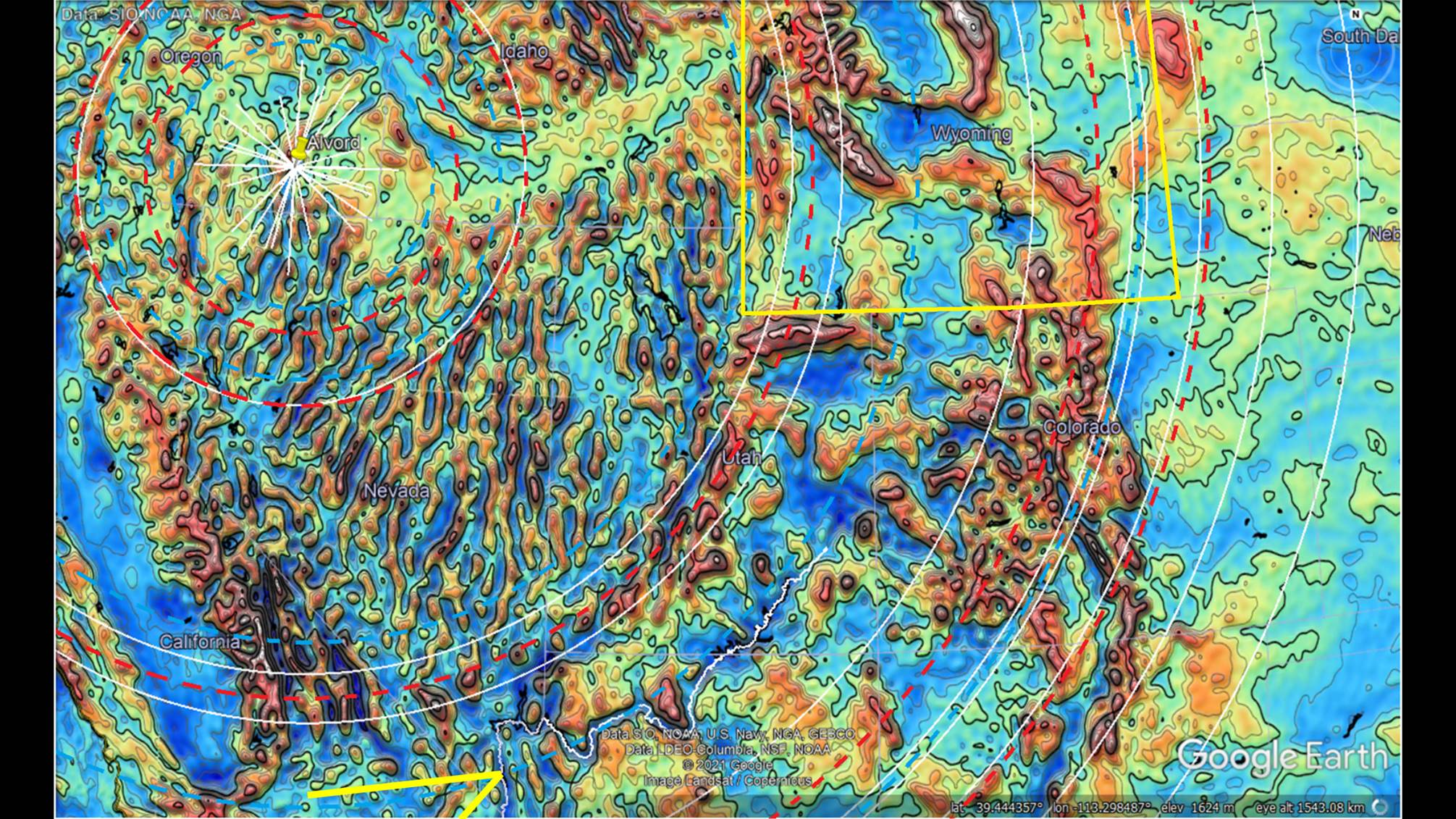

Figure 39: Looking at the Maka Luta crater’s pattern as it crosses the Rocky Mountains, it also produced a gravity pattern of ripples. When finding the cratering connection to the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, it quickly becomes evident something cut them off on their south end (yellow arrow). Part of that something was the wide dark-blue ring which includes Owens Valley and Death Valley, both very significant to geologist in California. While both had their ultimate shape determined by other, later craters. The first low gravity print was made by the Maka Luta crater, which included them in a release valley. Looking north from that area, a number of dark-blue areas are concentric to the Maka Luta’s expression all across the Basin and Range and Rocky Mountains. Figure 40: In Part 1 we discussed the Alvord crater that anchored the southern end of the Sevier Orogeny, and here we have identified the Tatanka and Maka Luta. In the southwest. Around the Grand Canyon, all three of these three craters overlap and produce some distinctive layers and interactions. In his Master thesis, Lathrop (2018) found the Bass Limestone’s Hotauta Conglomerate to correlate from Death Valley, California to the Franklin Mountains of West Texas, and the mud cracks correlated to the “molar-toothed” structures in the Belt-Purcell Supergroup of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada and Eastern Washington, Idaho, and Montana, U.S.A. except for the missing microsparry calcite infill or replacement. I propose that difference could be a result of higher temperature in the cratering process reflecting its shorter distance from the impact event. For these six distant disconnected deposits of Bass Limestone, Lathrop found a similar set of reverse faults hosted by each of the deposits that was concentric to the Alvord crater. By contrast to the diverse locations of the Bass/Unkar Group, the Chuar Group on top of it is only found in the Grand Canyon, to the north in the Chuar Field (6) where it is explored for petroleum, and the Uinta Mountains (7) of Utah. I propose the Bass Limestone was laid down by the Tatanka crater and then broken up over its range by the Alvord crater that followed. See Chapter 14 of my book for more thorough coverage of the Tatanka and Alvord cratering correlations.

Figure 40: In Part 1 we discussed the Alvord crater that anchored the southern end of the Sevier Orogeny, and here we have identified the Tatanka and Maka Luta. In the southwest. Around the Grand Canyon, all three of these three craters overlap and produce some distinctive layers and interactions. In his Master thesis, Lathrop (2018) found the Bass Limestone’s Hotauta Conglomerate to correlate from Death Valley, California to the Franklin Mountains of West Texas, and the mud cracks correlated to the “molar-toothed” structures in the Belt-Purcell Supergroup of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada and Eastern Washington, Idaho, and Montana, U.S.A. except for the missing microsparry calcite infill or replacement. I propose that difference could be a result of higher temperature in the cratering process reflecting its shorter distance from the impact event. For these six distant disconnected deposits of Bass Limestone, Lathrop found a similar set of reverse faults hosted by each of the deposits that was concentric to the Alvord crater. By contrast to the diverse locations of the Bass/Unkar Group, the Chuar Group on top of it is only found in the Grand Canyon, to the north in the Chuar Field (6) where it is explored for petroleum, and the Uinta Mountains (7) of Utah. I propose the Bass Limestone was laid down by the Tatanka crater and then broken up over its range by the Alvord crater that followed. See Chapter 14 of my book for more thorough coverage of the Tatanka and Alvord cratering correlations. Figure 41: Molar-toothed structures on the left from the Belt-Purcell Supergroup and evaporation cracks from the Bass Limestone’s Hotauta Conglomerate on the right. (D) is topside and (C) is underside. The irregular division and even fine lines are the same except for the microsparry infilling of the cracks. As microsparry calcite would have been produced at a specific temperature from the solution that the quartz sand grains were depositing in. This looks like a chemical difference governed by the temperature. This also suggest, both were deposited at an extremely elevated temperature, but in the Belt-Purcell it was somewhat higher temperature or prolonged elevated temperature than in the Hotauta Conglomerate.

Figure 41: Molar-toothed structures on the left from the Belt-Purcell Supergroup and evaporation cracks from the Bass Limestone’s Hotauta Conglomerate on the right. (D) is topside and (C) is underside. The irregular division and even fine lines are the same except for the microsparry infilling of the cracks. As microsparry calcite would have been produced at a specific temperature from the solution that the quartz sand grains were depositing in. This looks like a chemical difference governed by the temperature. This also suggest, both were deposited at an extremely elevated temperature, but in the Belt-Purcell it was somewhat higher temperature or prolonged elevated temperature than in the Hotauta Conglomerate. Figure 42: A cratering model for the Grand Canyon’s Pre Cambrian runs right up against Stromatolites, in the Hotauta Member of the Bass Formation, and in the Kwagunt formation of the Chuar Group. Are they fossils or are they chemistry? Partly because a cratering model would require them to be chemical, I will declare them to be. Also, I think that must be the default position, until identified fossil evidence is found to confirm a biogenic source. But, as same Creationist authors have publish their belief in a biogenic origin, I will say, I am not convinced. The lower right image does not look biogenic in origin to me. When I realize the containing strata was laid down very hot and a lot of chemical reactions were taking place as the very hot sediments were being put into place. These are conditions that have not been previously considered. I would propose to interpret them as the result of a chemical reaction that produced gases that lifted layers as it moved upwards in various forms including the inverted cone formation.

Figure 42: A cratering model for the Grand Canyon’s Pre Cambrian runs right up against Stromatolites, in the Hotauta Member of the Bass Formation, and in the Kwagunt formation of the Chuar Group. Are they fossils or are they chemistry? Partly because a cratering model would require them to be chemical, I will declare them to be. Also, I think that must be the default position, until identified fossil evidence is found to confirm a biogenic source. But, as same Creationist authors have publish their belief in a biogenic origin, I will say, I am not convinced. The lower right image does not look biogenic in origin to me. When I realize the containing strata was laid down very hot and a lot of chemical reactions were taking place as the very hot sediments were being put into place. These are conditions that have not been previously considered. I would propose to interpret them as the result of a chemical reaction that produced gases that lifted layers as it moved upwards in various forms including the inverted cone formation. Figure 43: Other mound and cone shaped “stromatolites” have been located by Lathrop in Vishnu Canyon and Bright Angel Creek West. Although these forms are less spectacular, I believe they confirm a non-biogenic origin for the structures. No one has previously considered the chemistry that is going on between rapid high temperature depositions of these strata atop each other within mere hours.

Figure 43: Other mound and cone shaped “stromatolites” have been located by Lathrop in Vishnu Canyon and Bright Angel Creek West. Although these forms are less spectacular, I believe they confirm a non-biogenic origin for the structures. No one has previously considered the chemistry that is going on between rapid high temperature depositions of these strata atop each other within mere hours. Figure 44: Atop the Unkar and Chuar Formations is the 60 Mile Formation. I think there is a lot of merit to Wise and Snelling (2005) suggestion that the 60 Mile formation is the start of the Tapeats. At this distance from the cratering center, the first result would be a thrust of the geography, with the resultant deposits of LARGE breccia. The sand that will eventually form the Tapeats would start early as a quartz and feldspar condensate from the vapor cloud. These lulls would be brief between episodes of thrusting, and the first sand lenses are small insertions. By the time that the Tapeats Sandstone proper is depositing, returning tsunamis from the thrusting have washed life forms back over the OCR and the platform has become stable. The thrust that the 60 Mile formation represents was not a start of the Flood, but the start of a single cratering event, not first but at least 5th in this region. In my two paper on the Tapeats, I was amazed that the strata was laid like in a river, and I compared that river for just the immediate area of the Grand Canyon would be a river 300 km (186 miles wide), Such rivers do not exist, and the Tapeats is not laid as on a beach. Hyperconcentrated flow was constantly depositing sand from a never ending source. To get that kind of deposition in a flume, you must keep adding sand to the recirculating water. Cratering supplies a continually renewing source of sediment, not from continuing erosion, but from continually condensing quartz from a very hot vapor cloud of vaporized rock that is slowly cooling. Cratering would produce the original thrust outwards carrying with it anything that can move. Water will rush back in to fill the void, filling it with hot condensing sediments and as they continues to fall, rush back outwards. Never getting very deep, 0.5 – 2 m (1.5-6 feet) in depth. This is the story of laying the thin layers of the Tapeats.

Figure 44: Atop the Unkar and Chuar Formations is the 60 Mile Formation. I think there is a lot of merit to Wise and Snelling (2005) suggestion that the 60 Mile formation is the start of the Tapeats. At this distance from the cratering center, the first result would be a thrust of the geography, with the resultant deposits of LARGE breccia. The sand that will eventually form the Tapeats would start early as a quartz and feldspar condensate from the vapor cloud. These lulls would be brief between episodes of thrusting, and the first sand lenses are small insertions. By the time that the Tapeats Sandstone proper is depositing, returning tsunamis from the thrusting have washed life forms back over the OCR and the platform has become stable. The thrust that the 60 Mile formation represents was not a start of the Flood, but the start of a single cratering event, not first but at least 5th in this region. In my two paper on the Tapeats, I was amazed that the strata was laid like in a river, and I compared that river for just the immediate area of the Grand Canyon would be a river 300 km (186 miles wide), Such rivers do not exist, and the Tapeats is not laid as on a beach. Hyperconcentrated flow was constantly depositing sand from a never ending source. To get that kind of deposition in a flume, you must keep adding sand to the recirculating water. Cratering supplies a continually renewing source of sediment, not from continuing erosion, but from continually condensing quartz from a very hot vapor cloud of vaporized rock that is slowly cooling. Cratering would produce the original thrust outwards carrying with it anything that can move. Water will rush back in to fill the void, filling it with hot condensing sediments and as they continues to fall, rush back outwards. Never getting very deep, 0.5 – 2 m (1.5-6 feet) in depth. This is the story of laying the thin layers of the Tapeats. Figure 45: If the Tatanka crater formed the Unkar Group, and the Alvord crater formed the Chuar Group, the next sedimentary layer is the Tapeats Sandstone. Clarey (2017) compiled the Sauk Group, and his map is redrawn in B. It maps the Tapeats Sandstone and equivalent sandstone all over the continent that fits the Maka Luta and Foxe craters. Additionally, it has an arch across the central states that Clarey identifies as “dinosaur peninsula.” I propose that arch was an up-thrust of the earlier Keys crater. In the far north the pattern of sandstone was altered by the Greater Beaufort crater that also produced the Franklin Large Igneous Province just south of the depositing sandstone.

Figure 45: If the Tatanka crater formed the Unkar Group, and the Alvord crater formed the Chuar Group, the next sedimentary layer is the Tapeats Sandstone. Clarey (2017) compiled the Sauk Group, and his map is redrawn in B. It maps the Tapeats Sandstone and equivalent sandstone all over the continent that fits the Maka Luta and Foxe craters. Additionally, it has an arch across the central states that Clarey identifies as “dinosaur peninsula.” I propose that arch was an up-thrust of the earlier Keys crater. In the far north the pattern of sandstone was altered by the Greater Beaufort crater that also produced the Franklin Large Igneous Province just south of the depositing sandstone. Figure 46: That these tsunamis might contain live vertebrates seems unlikely, but at Plateau Point just out from Indian Gardens just off the Bright Angel Trail we have evidence of exactly this. In my article from the Summer 2014 CRSQ, Anomalous Impressions in Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian), Grand Canyon, the editors would not let me refer to them as footprints, but I showed that they had all of the characteristics of footprints and occurred in trackways, so I think I can defend them as footprints.

Figure 46: That these tsunamis might contain live vertebrates seems unlikely, but at Plateau Point just out from Indian Gardens just off the Bright Angel Trail we have evidence of exactly this. In my article from the Summer 2014 CRSQ, Anomalous Impressions in Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian), Grand Canyon, the editors would not let me refer to them as footprints, but I showed that they had all of the characteristics of footprints and occurred in trackways, so I think I can defend them as footprints. Figure 47: See the article for much better images. At the top is a documentary set of photos of most of the site. The entire ledge is shown with a total of 32 whole or partial impressions, produced in 6 trackways of similar prints. A horse, 2 large cats, a 3-toed theropod, a web footed bird, and one small mammal. At least the Theropod, horse and large cats were running on a water saturated, thixotropic surface. If water was moving over the surface when the prints were made, it would have to be less than 12-14 cm deep. The left image shows trackway A and the right image is one of the individual prints, possibly a large cat (#2).

Figure 47: See the article for much better images. At the top is a documentary set of photos of most of the site. The entire ledge is shown with a total of 32 whole or partial impressions, produced in 6 trackways of similar prints. A horse, 2 large cats, a 3-toed theropod, a web footed bird, and one small mammal. At least the Theropod, horse and large cats were running on a water saturated, thixotropic surface. If water was moving over the surface when the prints were made, it would have to be less than 12-14 cm deep. The left image shows trackway A and the right image is one of the individual prints, possibly a large cat (#2). Figure 48: There are no dinosaur eggs found in the Grand Canyon, but this is as good a time to talk about the conditions where dinosaur eggs are found in the Dinosaur Peninsula. In my September 2004 article in CRSQ on dinosaur eggs and nest, I emphasized how dinosaur eggs are often found in thinly layered sediments which give the impression that the sediments were depositing while the eggs were being laid. Some clutches of eggs were even laid into sand partially suspended in the saturating water. If dinosaurs were laying their eggs into water they were highly stress, desperate to survive. It is a reasonable assumption that dinosaur eggs, like bird or reptile eggs, must be incubated on dry land or embryo will drown. Both chicken and marine turtle’s eggs will drown in a few minutes of being submerged, about the same amount of time that you will last submerged. No reptiles lay their eggs in the water. So why would dinosaur do so? Obviously, they needed to get rid of the eggs for their own attempted survival. Eggs and foot prints are evidence of aerial exposure of shallow actively depositing sediments. Model shown at right is typical of those produced in museums. Baby dinosaurs are made the size of embryos found in the egg, and are only half as large as hatchling for the egg size. Many Dinosaurs were probably ovoviviparous, bearing live young, and eggs represent aborted gestation due to stress and survival instinct (Psalms 29: 9).

Figure 48: There are no dinosaur eggs found in the Grand Canyon, but this is as good a time to talk about the conditions where dinosaur eggs are found in the Dinosaur Peninsula. In my September 2004 article in CRSQ on dinosaur eggs and nest, I emphasized how dinosaur eggs are often found in thinly layered sediments which give the impression that the sediments were depositing while the eggs were being laid. Some clutches of eggs were even laid into sand partially suspended in the saturating water. If dinosaurs were laying their eggs into water they were highly stress, desperate to survive. It is a reasonable assumption that dinosaur eggs, like bird or reptile eggs, must be incubated on dry land or embryo will drown. Both chicken and marine turtle’s eggs will drown in a few minutes of being submerged, about the same amount of time that you will last submerged. No reptiles lay their eggs in the water. So why would dinosaur do so? Obviously, they needed to get rid of the eggs for their own attempted survival. Eggs and foot prints are evidence of aerial exposure of shallow actively depositing sediments. Model shown at right is typical of those produced in museums. Baby dinosaurs are made the size of embryos found in the egg, and are only half as large as hatchling for the egg size. Many Dinosaurs were probably ovoviviparous, bearing live young, and eggs represent aborted gestation due to stress and survival instinct (Psalms 29: 9). Figure 49: The Grand crater centers in Eastern Utah, just happens to exactly match the depositional area of the Coconino Sandstone and related Schnebly Hills Sandstone just under it, and equivalent sandstones from Texas to Montana. The yellow oval is the location of the Fort Apache Limestone. We will come back to the limestone.

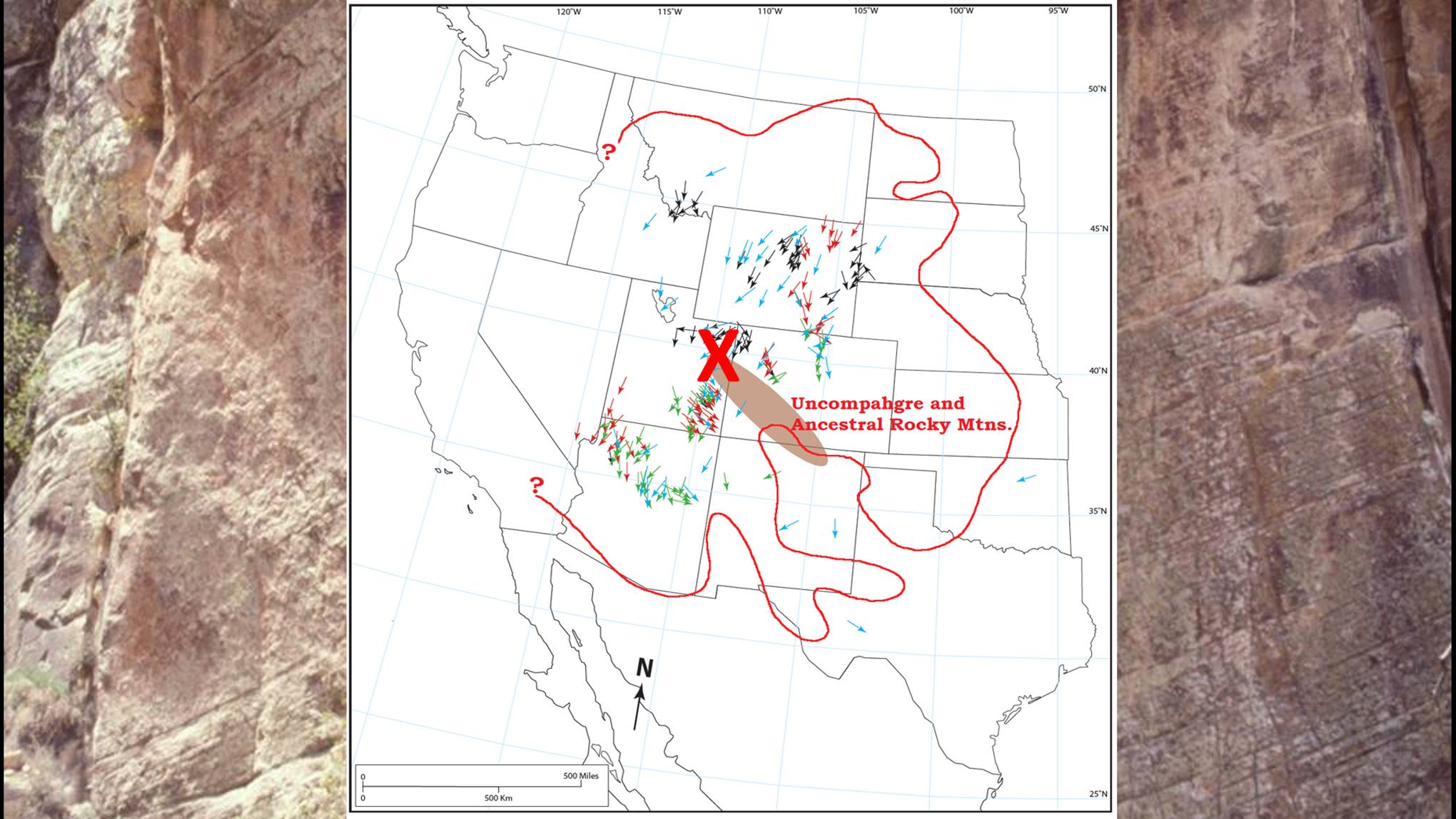

Figure 49: The Grand crater centers in Eastern Utah, just happens to exactly match the depositional area of the Coconino Sandstone and related Schnebly Hills Sandstone just under it, and equivalent sandstones from Texas to Montana. The yellow oval is the location of the Fort Apache Limestone. We will come back to the limestone. Figure 50: First, we want to see the depositional pattern of the Coconino and Schnebly Hills sandstones. Dr. John Whitmore is the expert, not I. His map, above, traces the depositional flow patterns found in these formations. This flow pattern would support movement primarily in the Coriolis direction or possibly another large crater in the Great Lakes region. This suggest continuing deposition significant hours after the cratering event. Geologist generally recognize the Uncompahgre and the Ancestral Rocky Mountains as the source for the sand grains, but I would propose an alternative. They originated as condensates under a vapor cloud from the Grand crater.

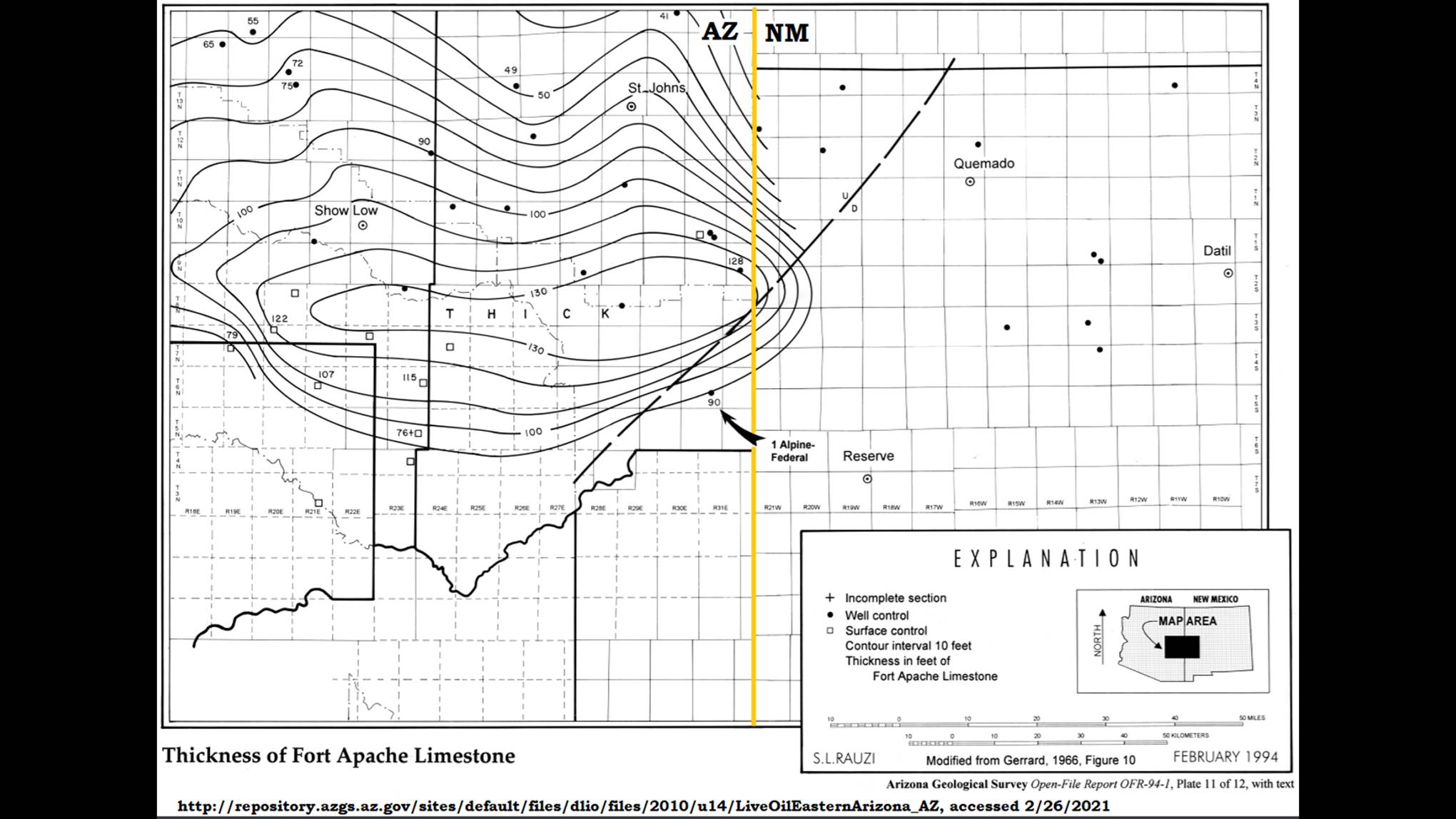

Figure 50: First, we want to see the depositional pattern of the Coconino and Schnebly Hills sandstones. Dr. John Whitmore is the expert, not I. His map, above, traces the depositional flow patterns found in these formations. This flow pattern would support movement primarily in the Coriolis direction or possibly another large crater in the Great Lakes region. This suggest continuing deposition significant hours after the cratering event. Geologist generally recognize the Uncompahgre and the Ancestral Rocky Mountains as the source for the sand grains, but I would propose an alternative. They originated as condensates under a vapor cloud from the Grand crater. Figure 51: Fort Apache Limestone occurs between two layers of the Schnebly Formation in the area of Sedona, and makes only a spotty appearance at the Mogollon rim, but grows thicker as it approaches the New Mexico border. The far right image raises another question as it shows the sedimentary strata in the Sedona area. Devils Kitchen is a sinkhole that Lindberg connects to the Redwall strata below. Sources from the Hualapai Indian Reservation area cite sinkholes that originate in the Tapeats sandstone or below. I propose the sediments were laid down at high temperature and the flowing water that deposited them was not adequate to cool them. The life forms that interacted with the strata have to be consider as reacting to significantly hot strata. The breccia pipes that underlay the sinkholes are gas escape columns formed by escaping gasses from the mantle or lowest crystalline layers.

Figure 51: Fort Apache Limestone occurs between two layers of the Schnebly Formation in the area of Sedona, and makes only a spotty appearance at the Mogollon rim, but grows thicker as it approaches the New Mexico border. The far right image raises another question as it shows the sedimentary strata in the Sedona area. Devils Kitchen is a sinkhole that Lindberg connects to the Redwall strata below. Sources from the Hualapai Indian Reservation area cite sinkholes that originate in the Tapeats sandstone or below. I propose the sediments were laid down at high temperature and the flowing water that deposited them was not adequate to cool them. The life forms that interacted with the strata have to be consider as reacting to significantly hot strata. The breccia pipes that underlay the sinkholes are gas escape columns formed by escaping gasses from the mantle or lowest crystalline layers. Figure 52: The Fort Apache Limestone is a relatively thin strata arriving in the middle of the Schnebly Hills sandstone. It was blown to the south by the same wind that carried the Coconino and Schnebly sandstones in that direction.

Figure 52: The Fort Apache Limestone is a relatively thin strata arriving in the middle of the Schnebly Hills sandstone. It was blown to the south by the same wind that carried the Coconino and Schnebly sandstones in that direction. Figure 53: The Fort Apache Limestone commonly has Bryozoan fossils and occurs in extreme eastern Arizona, overlapping New Mexico, I associate it with the Petrified Forest crater, To see the crater, we need a larger area view, but I brought the view closer to see the county lines to show the association between the area of the limestone and the area of the crater.